Jonestown: The Women Behind the Massacre: A Review

I have to confess at the outset, I had low expectations for this program. A&E, which started out as a sort of PBS-styled cable network, has been sinking in the muck of reality television for more than a decade, and so I expected the visual equivalent of those quickie paperback books about Peoples Temple that came out in 1978 and 1979. I was surprised at the quality of the finished product.

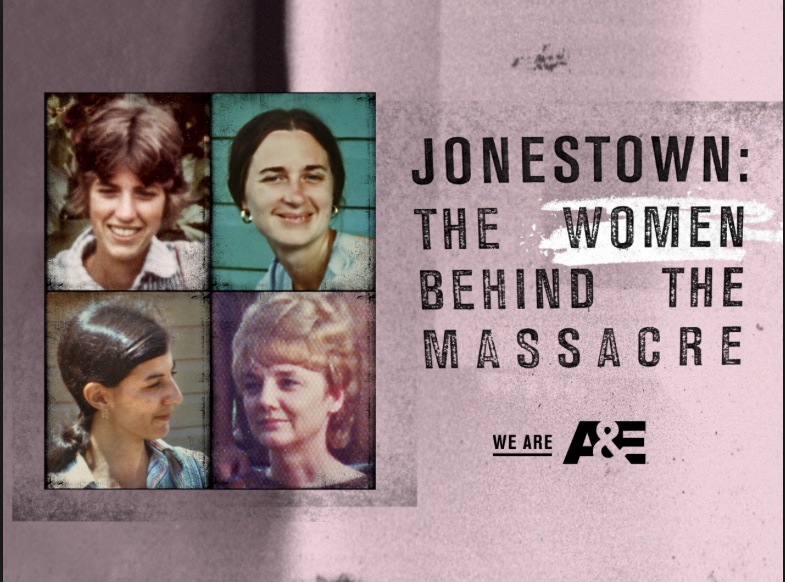

As the title suggests, the documentary focuses on four women in Jim Jones’ life: his wife, Marceline; and Carolyn Moore Layton, Annie Moore, and Maria Katsaris, three members of the Planning Commission who made up the inner circle. The documentary has two goals. First, it has to tell the story of Peoples Temple and Jonestown to viewers who may not have any familiarity with it, which by itself is a difficult mission to accomplish in 83 minutes. And second, it must prove the culpability of those four women in the final White Night.

As the title suggests, the documentary focuses on four women in Jim Jones’ life: his wife, Marceline; and Carolyn Moore Layton, Annie Moore, and Maria Katsaris, three members of the Planning Commission who made up the inner circle. The documentary has two goals. First, it has to tell the story of Peoples Temple and Jonestown to viewers who may not have any familiarity with it, which by itself is a difficult mission to accomplish in 83 minutes. And second, it must prove the culpability of those four women in the final White Night.

The thesis of this documentary is presented near the beginning. After the customary shots of the bodies at Jonestown and a segment from the so-called Death Tape with Jones encouraging people to get their “medication,” Rebecca Moore – Jonestown scholar and sisters of two of the women – says, “People want to blame Jim Jones for the deaths and certainly in many respects, it was his vision, but he couldn’t have done it by himself.”

The filmmakers do an admirable job in reaching the documentary’s first goal. The highlight reel of Peoples Temple is covered in a straightforward manner, largely by using an interview with another Jonestown scholar, Mary Maaga, to narrate its history. Some things are skipped: the film leaves Indiana about seven minutes in, the years that the Jones family spent in Brazil are absent, Ukiah is barely mentioned, and Jones’ accumulation of political power in California is largely ignored. Still, for a snapshot of Peoples Temple history, it serves its purpose, covering the group’s last decade of growth, recruiting trips, the founding of Jonestown, the custody battle over John Victor Stoen, the Concerned Relatives, Leo Ryan, and the cataclysmic ending.

Woven into this overarching narrative are the four women. They are introduced in chronological order. Stephan Jones, the only biological son of Jim and Marceline, speaks fondly of his mother and her qualities, and what he thinks the attraction between his parents was.

The other three are introduced once the narrative moves to California. First is Carolyn Moore Layton, the woman whom Mary Maaga refers to as Jim’s “California wife.” An effective back-and-forth sequence occurs when Stephan and Rebecca discuss how the two families, Marceline and the Moores, in their own way found out about an affair involving Carolyn and Jim.

Here, much time is spent here trying to ascertain why Marceline simply did not leave once she found out about Carolyn in 1969, nor why she stayed after Carolyn became pregnant with Jim’s son Kimo in 1974. Stephan believes his mother remained because she simply was not aware of the options she had in leaving; Maaga suggests that Marceline may have felt she would have lost her Peoples Temple family and the opportunity to transform the world. Marceline may have publicly accepted that she had to make sacrifices by sharing her husband, Maaga continues, but privately she never fully accepted this. Moore also wonders whether Marceline stayed for the reflected glory that came from being Jim’s wife and from being the “Mother” of Peoples Temple, an idea Stephan disagrees with.

There is also a discussion about what exactly the women got out of their affairs with Jim. Stephan mentions the “prestige” and intoxicating effect that would be generated by being chosen. Maaga believes that some women wanted power over Jim, and that they got that power and authority that otherwise would have been unavailable to them. Later, after the move to Jonestown and Jones’ addiction to downers, Jones began serving the women rather than the other way around. For viewers who wonder how this “inner circle” of Peoples Temple leadership could buy into Jim’s delusions, Rebecca Moore explains that Jim told lies – such as that the Guyanese army and the United States Army were going to come in and slaughter them – and the people believed them, and no one was willing to break that cycle. Stephan believes that the four women were so compromised, and had bought into Jim’s hustle for so long, that they could not let themselves out. We act surprised when it happens, but the Manson Family did it, the Ant Hill Farm cult did it, Heaven’s Gate did it, Aum Shinrikyo did it, and it’s still happening today.

The third woman in the mix is Annie Moore, who shared her sister Carolyn’s educated, stable, middle-class background, traits of many in the larger Temple leadership group. Unlike Carolyn, though, who came to the Temple as a wife and a college graduate, Annie joined shortly after finishing high school in 1972. Rebecca says Annie approached Peoples Temple like she was joining a convent. She sold her possessions and cut her hair. But her rise in leadership was noted by the disaffected youth who would soon form the Eight Revolutionaries. One of their grievances was the notable rise of white women into positions of leadership while only a few token blacks of either sex attained those positions. The Eight Revolutionaries also complained about the great deal of sex and sex talk going on, something Rebecca reinforces by describing the sex talk in the letters her sisters wrote home.

Another young white woman who rose quickly in leadership was Maria Katsaris. No one from her family appears on camera to discuss her background, and the closest the film comes are interviews with Jonestown survivors Jordan Vilchez and Laura Johnston Kohl. The latter also provides commentary, calling Maria “naïve,” which was probably true, and that Jim targeted her because “he liked young meat.” Maria’s influence is documented by another former Temple member, Hue Fortson, Jr. who relates that rank-and-file members like himself did not speak to either Maria or Carolyn, unless they spoke to them first. Finally, Jonestown survivor Leslie Wagner-Wilson states that she felt both women believed themselves to be better than others because they were chosen to be with Jim, thus having the intoxicating prestige Stephan mentions earlier.

With the identities established, the film then moves to the subject of the women’s culpability in the mass deaths. Carolyn is implicated by memos she wrote in Jonestown. Annie also wrote memos, including one which suggests the possibilities of poison as a solution for mass killing. There’s no written evidence for Maria Katsaris, but multiple witnesses attest to her willingness to do whatever Jim required.

The sticky point is Marceline Jones, and on her, the interviewees disagree. Stephan Jones flatly states that he does not believe that his mother was involved in orchestrating a mass murder/suicide. Mary Maaga believes that Marceline is complicit by her silence and inability to stop the final White Night, adding that Marceline may have simply been too exhausted to resist after years of watching her marriage crumble and her dreams dashed to dust.

What isn’t explained is Jim’s cryptic call to Marceline on the death Tape that she has forty minutes. In Jeff Guinn’s Road to Jonestown (445-46), Jim Jones, Jr. suggests that Jones is telling Marceline that all of her children, including the ones in Georgetown, will be dead in forty minutes, and that may have crushed whatever resistance Marceline still had. Others have proposed that Jones is referring to the length of time it would take Guyanese troops to travel from Port Kaituma and Jonestown after the assassination of Leo Ryan. Wagner-Wilson assigns blame to all four women by labeling them “enablers” which is true enough, although I still wonder about Marceline’s thoughts on that day.

I had concerns about the re-created scenes with a grainy 70s home movie effect added to them, but it turned out to be innocuous except for the depiction of Maria. “Marceline” is shown as she puts on make-up, “Jim” and “Carolyn” walk through the woods, “Annie” leans in a hammock writing letters. But “Maria” appears in bed playing peek-a-boo with the sheets. While this might fit with Johnston Kohl’s reference to Maria as “young meat,” it was Carolyn who bore Jim a son. I know that Maria was not a pleasant person, but she was a Temple treasurer, so maybe the filmmakers could have shown her counting money rather than rolling around on a bed.

The only other problem I have – although this is not the filmmakers’ fault – is that, especially when compared with the other three women, there is no background given on Maria. A quick check of other documentaries reveals a similar lack of information – either documentarians were unable to locate relatives, or the Katsaris family declined to participate – but it leaves her a cypher.

Aside from the problems surrounding Maria’s depiction, this is worth seeing. There are several pieces of film footage I had never seen before, and some of it is truly heartbreaking, particularly the footage of children in Jonestown having a parade with costumes and signs. The documentary accomplishes what it set out to do by explaining the enablers who helped Jim Jones commit this atrocity.

But I am also left with a question: will there be a “Men of Jonestown” documentary? Larry Schacht (I refuse to call him Doctor) bought the cyanide and figured out the proper proportions needed for a mass murder/suicide. Jim McElvane shut down Christine Miller’s arguments against mass suicide. The identified shooters at the airstrip – and Larry Layton, the only person who faced any kind of prosecution for the events in Jonestown that day – were all male. And the armed security guards who stood around while three hundred children were murdered were primarily male. I think the filmmakers focused on these four women only because they were part of the inner circle who got the process rolling and – if the producers are honest about it – because of the shock value of the perpetrators’ sex. Men committing atrocities no longer has shock value – we are used to that – but women who organize and plan mass murder? That still has the capacity to shock and titillate.

I recognize that 83 minutes isn’t a lot time to go deep, so I can only hope that future efforts will widen the circle of enablers and allow us to see how second and even third tier leaders also contributed.

(Jason Dikes holds a degree in broadcast communications from Stephen F. Austin State University, an MA in history from the aforementioned institution, and an MLS from The University of North Texas. He currently is an adjunct professor American history at Austin Community College and a cataloging librarian for the City of Round Rock. His other article in this edition of the jonestown report is The 2018 Peoples Temple podcast review. His collection of articles for this site may be found here. He may be reached at jdikes@austincc.edu.)