Between 18 October 1977 and 18 November 1978, Richard Tropp had been hard at work. During the last thirteen months of his life, he was responsible not only for overseeing Jonestown’s entire schooling program, but also for teaching the high-school age children who had come to Guyana with their families hoping for a better life. As if organising an educational curriculum for three hundred children wasn’t enough, Tropp was also a leader within the Peoples Temple Publications Department. Often credited as Jonestown’s most prolific writer, Tropp was deeply engaged with the majority of the community’s publications output. But he is perhaps best known as the author of the community’s suicide note, left in the wake of 18 November (a note which, whilst unsigned, is largely accredited to Tropp’s hand).

But it is one of Tropp’s less well-known writings that has occupied increasing space in my mind. It is an unfinished (and characteristically unsigned) manuscript of a proposed book on Temple history, and an exposé on the conspiracies believed to be operating against it. An incomplete copy of this manuscript has been available on this site for some time. I remember reading through this document for the first time five years ago and finding myself in complete agreement with the Jonestown Institute’s summary of the material as “somewhat unfocused, disorganized, repetitious, and overwritten.” It is all of these things and more. It is a messy blend of political idealism, community history, Jones-worship, score-settling, and conspiracy thought all blended into one potent cocktail of misinformation and adulation. In this way, it is a perfect textual microcosm of what the community in Jonestown devolved into as they unwittingly approached 18 November 1978.

During my visit to the California Historical Society’s archives in Summer 2023, I was pleasantly surprised to find myself face to face with Tropp’s complete manuscript, including the pages that had been missing on this site’s initial scans. There was a bunch of other material archived alongside the main document, ranging from footnotes to appendices to instructions for editorial reading. I tucked these scans away into a folder for some time, until I had completed and submitted my dissertation for PhD examination. Completing my own book-length manuscript has brought me a new perspective on Tropp’s manuscript, which I am now far more sympathetic towards. After all, which student of the humanities can honestly say their work has never been described as “unfocused, disorganised, repetitious, or overwritten” at some point? Tropp was wrestling with the very thing we scholars grapple with: the organisation and condensation of vast amounts of materials into a singular, purposeful, and (hopefully) entertaining script.

Like the majority of authors who complete a first draft, Tropp wasn’t quite successful in meeting these aims. This manuscript, however, shouldn’t be read as if it were the final product. Doing so would mitigate its value: a value which is only increased by its unfinished, rough-around-the-edges state. Across the arts and humanities, the value of arts non finitoare well known. One author writes that unfinished works are “[s]uspended in a state of coming-into-being,” and that “they present new perspectives on an artist’s creative process as well as on an artwork’s historical context.” I contend that, much like an unfinished portrait or sculpture, Tropp’s manuscript deserves a reappraisal from this perspective. It is precisely because this work was left unfinished that it can offer us such a revealing insight into Jonestown, as well as into the mind of its chief author.

This article reintroduces Tropp’s complete manuscript – alongside its introductory note and footnotes and appendices – the supporting materials scanned at the California Historical Society. I urge anyone who reads these documents to do so with more than a pinch of salt. Rather than an accurate portrayal of Temple history, they offer a demonstration of the way in which conspiracy theories are structured and created.

“Instructions and Explanation Notes to Readers of this Manuscript.”

In keeping with the intention of the author of these materials, I open this presentation with the document that was intended to be read prior to the manuscript itself. Entitled “Instructions and Explanation Notes to the Readers of this Manuscript,” this instructive document was an assistive piece which aimed to guide its readers and editors through the material, whilst clarifying the perspective of its author and streamlining the feedback process. It provides information on the intended details of the publication, including a title which has been unknown until this time. The author of the manuscript had suggested the work be called “Target: Jim Jones and Peoples Temple,” even going so far as to provide a mock-up sketch of a potential cover for publication which involved a crosshair over the face of Jim Jones, surrounded by photographs representing the major sections of the community: seniors, children, families, so on, so forth. Figure 1 is taken directly from this document, likely drawn by Tropp’s own hand.

This proposed cover is suggestive of the way the author of this manuscript viewed Jonestown’s increasingly fragile relationship with the outside world. Believing the community to be at the centre of a conspiracy binding together apostates, relatives, and the United States Government into a single cabal of capitalist evil hellbent on quashing Jonestown, the artwork suggests that it is not just Jim Jones in the scope of the assassin’s gun. Whilst the crosshair may be trained on Jones, he is surrounded by different cross sections of the Jonestown community. Indeed, whilst Jones may be the primary Target, the entire Peoples Temple community would be the collateral damage.

The remainder of this instructive document contains other details prior to publication, including details for a publication page. As to who the published author should be, the Instruction document simply asks “who, if any?” On the one hand, this could reflect Tropp’s own humility – he did, after all, leave his final letter unsigned – but it could also reflect the notion that this work was a communal effort. Indeed, whilst Tropp was likely the lead author, this manuscript was not the product of his hand alone. Present throughout each document and the entire manuscript are hand-written editorial comments written by those in the Jonestown leadership who reviewed the work. Towards the end of the instructive document, for example, a typed note reads: “After this manuscript was read by Harriet [Tropp], Carolyn Layton, and Jim, several changes have been made… we have tried to note many of the changes on the manuscript itself.” At the very least, the manuscript is the product of Harriet and Richard Tropp, Carolyn Layton, and Jones himself as the ever-present creative director.

Jones’ presence in the manuscript is not limited to editorial notations made in margins. His presence suffuses the entire work. Such a fact is particularly evident when comparing Tropp’s initial suggestion for a dedication, with substitute language scribbled alongside it. Tropp’s initial dedication would have read “To the children of the world.” A revised dedication hastily written into the margin reads “Dedicated to the children of Jonestown, [some] of whose lives and liberty Jim Jones has [vowed] to defend, with his life, if necessary.” What could have been a noble platitude was revised to place Jim, and not the children of the world, at centre stage.

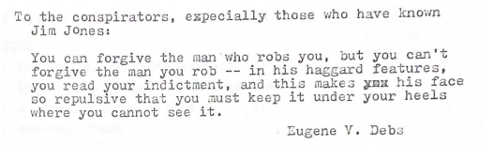

Throughout the manuscript, the tension between a noble work written for the children of the world and a targeted piece intended to humiliate the “members of the conspiracy” – i.e., the Concerned Relatives – remains ever present. Beneath the dedication a quotation is suggested, seen in Figure 2:

Whilst Book 1 of the manuscript indeed covers the early period of Temple history, its focus remains on Jones as the architect of the community. This is somewhat disappointing, as we know that Richard Tropp was working on an oral history project composed from interviews held with longstanding Temple members. As he made pains to note in his final letter, he requested that posterity “[p]lease see the histories of our people that are in a building called teachers resource centre.” These texts, Tropp had hoped, would be presented to Ryan during his fateful November visit to Jonestown. But these oral histories would never make it into a manuscript; instead, it appears that Tropp’s creative energies were largely consumed by Target, another work which would remain incomplete and unfinished.

Building a Conspiracy.

Tropp’s Target manuscript is not particularly useful as a historical work. It is, however, remarkably valuable in the ways that it presents to us a snapshot of the processes by which conspiracy thought was structured, streamlined, evidenced, and communicated. As any good historian knows, the footnotes of a text can be its most valuable accompaniment. Tropp’s manuscript is no different; the main text is accompanied by 57 footnotes which range from Biblical quotations to references to newspaper articles and, more commonly, references to the Temple’s other publications such as the Peoples Forum. Some references are little more than further opportunities to glorify Jones in an act of textual mythmaking. See, for example, footnote 5 reproduced below:

Other footnotes are used as little more than opportunities to refute certain accusations levelled at Peoples Temple and Jonestown. Footnote 50, for example, attempts to refute the claims made by private investigator Joe Mazor – who at the time was working for the Concerned Relatives – concerning the alleged abduction of children and the assertions that Jonestown’s residents were not free to leave the community. Whilst the first of the two claims was largely false, it was however true that residents were not free to leave the community, having their passports confiscated by Jones and the leadership circle. Footnote 50 does little more than repeat the lie that residents were free to leave:

Hoping this document would be published and read by a news-consuming American public, footnotes such as these give the document a veneer of academic respectability. All too often, however, they encapsulate the lies and circular logic of Jonestown’s leadership as they suggest that continuous repetition of their own claims thereby validates them. Many footnotes are incomplete references to unnamed appendices, most of which are not included among the documents held at the California Historical Society.

Tropp projected five appendices to accompany the main work. The “Instructions” document provides a list of appendices and their suggested topics. Appendix 1 was earmarked to include “most of the material: supporting documents, letters, reprints of articles.” Appendix 2 was intended to be about Jonestown, an “explanation of the project … plus the text of the Summer report, if feasible to include.” Appendix 3 was intended to be the “Unita Blackwell Wright” appendix, including Peoples Forum articles, “letters of inquiry and response, supporting documents.” Appendix 4, the “Grace Stoen appendix,” was envisioned as an explanatory document detailing “the paternity of John Stoen.” Understanding the sensitivity of this issue, however, Tropp noted that “we may want to omit” this particular appendix, including a comment requesting advice on whether or not to include it. The final appendix, number five, was sketched out as “Articles and letters of support for the Temple and Jim Jones. Extensive.” It is remarkable how much material was planned for these supporting documents, even if they merely provided opportunities to restate what had been said many, many times before.

I encourage everyone to read through Tropp’s manuscript, including its supporting documents. Whilst these materials are unlikely to shed any new light on Peoples Temple’s complicated history or its relationship with wider American society, I do believe they illuminate and emphasise the importance of the conspiracy fervour which spread throughout the community during the last year of its life in Jonestown, Guyana. The conspiracy of the magnitude envisioned by Jones and his leadership circle may never have existed in reality, but this document serves as further evidence that it genuinely existed in the minds of Jonestown’s sharpest thinkers.

(Originating from Chatham, Kent, and now living in London, UK, Connor Ashley Clayton holds an MA in Modern History from from The University of Warwick, and a PhD from Queen Mary University of London. He is a regular contributor to the jonestown report. He is a regular contributor to the jonestown report. His complete collection of articles for this site is here. He can be reached at connorclayton96@gmail.com.)