(Emerson Maureen Stuckart submitted this thesis in January 2014 in completion of a requirement for a Degree of Master of Arts at the Heidelberg Center For American Studies at the Ruprecht-Karls-Universität-Heidelberg in Germany.)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

New Religious Movement or Cult?

- Birth of the Reverend

- Peoples Temple Full Gospel Church

- The Exodus – California Dreaming

- God is Love, Love is Socialism

- The Jungle Paradise

- The Unwilling Boy Pawn

- Endless White Nights

- Let’s Make it a Beautiful Day

“The new heaven on earth represented by the Peoples Temple was first a church, then a subversive revolutionary movement, and finally a socialist utopia.”[1]

Families lay next to each other. Mothers held their children tight to their chests. Friends and lovers of all racial backgrounds held hands. Almost all lay face down in the warm, tropic jungle, their bright and cheerfully colored clothing creating a stark contrast to the grim reality of the scene. This image, of almost 1000 Americans lying dead in the Guyanese jungle, has become synonymous with the legacy of Peoples Temple. On 18 November 1978, Reverend James “Jim” Jones systematically ordered the mass murder and suicide of his congregation. After the group and its demise was sensationalized in the American press, “Jonestown became a kind of lens through which the U.S. public viewed all new and alternative religious communities.”[2] Peoples Temple would serve as a sort of litmus test, by which emerging new religious movements would be subject.

Peoples Temple was many things; new religious movement, socialist utopian experiment, and agricultural commune. The movement, which aimed to incorporate Marxist socialism within the context of Evangelical Pentecostalism, arose in the early 1950s. Under the leadership of ordained minister Rev. Jones, Peoples Temple transcended religious, social, and political ideologies. Originally, his congregation was strongly influenced by Evangelical Pentecostalism, as well as aspects of the Holiness Movement and the New Thought Movement. Peoples Temple did not begin as a deviant group, but as the movement grew and relocated, the ideological concepts evolved and the church began to move further from its roots – both dogmatic and geographic.

Rev. Jones began his movement as an attempt to combat growing racial tensions in Indiana. Disgusted by the fact that “Sunday was the most segregated hour,”[3] Rev. Jones established his own racially-integrated church. The message was a combination of socialism and religious communalism. “He combined the Apostle Paul’s mandate for Christians to pool their resources and Karl Marx’s directive ‘From each according to his ability, to each according to his need,’ and called it apostolic socialism.”[4] The goal was to create a safe, integrated place of worship, free from racial prejudice. Coinciding with his message of integration, Rev. Jones preached social awareness and the importance of creating a racially and economically equal community.

Peoples Temple is marked by three specific ideological phases, corresponding to the geographic locations of the church. The group began in Indiana but subsequently moved to California and then finally Guyana in South America. Each phase of Peoples Temple represents a dramatic shift in the ideology espoused by Rev. Jones, as well as a change in the lifestyles of members. Peoples Temple literally and figuratively moved further away from its Pentecostal roots with each exodus; Rev. Jones continually changed his message and created a fear of persecution, providing legitimacy for each geographic relocation.

As a small child, Rev. Jones was fascinated with religion. A poor boy seeking acceptance, he eventually found comfort and acceptance in a Pentecostal church. Religion consumed his adolescent years, and he began to preach equality and racial integration on the street corners of Indianapolis, Indiana. During the 1950s, Rev. Jones sought to provide a safe place for people of all ages and colors to worship. He began as an evangelical Pentecostal preacher, encouraging members to accept all members of society. As membership increased, Rev. Jones began to adopt apocalyptic millennialist tendencies, going so far as to suggest imminent thermonuclear war. Using this vision as justification, Rev. Jones encouraged the relocation of Peoples Temple to California, a place viewed as safe and accepting of all individuals.

In California, Rev. Jones and Peoples Temple continued as a religious group. He continued with his traditional Pentecostal practices, but slowly began to incorporate aspects of the social gospel and political Marxist theory. At this time, Peoples Temple evolved from a fundamentalist religion towards social activism. Marx and similar teachings replaced the Bible and the word of God. Rev. Jones became more politically active and encouraged members to live communally, sharing virtually everything in a cooperative, integrated social experiment. As the behavior of Rev. Jones became more erratic and members began to feel persecuted for their progressive belief structure, another exodus became necessary. By the middle of 1977, about 1000 members of the congregation, including Rev. Jones and his family, had moved to their own jungle paradise in Guyana.

Located on the coast of South America, Guyana represented everything Peoples Temple had been working towards. The country, once a former colony of Great Britain, had a majority black population. The government was socialist and the main language spoken was English. Members would not face persecution based upon their political beliefs and they would not have to learn a foreign language, though many had begun learning Russian. Guyanese officials were excited that such a progressive, integrated, and seemingly socialist group had chosen their country. Beginning in 1975, a select group of members began to carve a settlement out of the jungle, building a community space from almost nothing. Peoples Temple deemed their experiment an agricultural project, one they hoped to develop into a self-sustained utopian community. This phase of Peoples Temple is marked by more perceived cult-associated behaviors and activities, while outwardly projecting an image of socialist utopianism. Sadly, Peoples Temple ended abruptly in November 1978, when 918 people were killed or voluntarily committed suicide, what Rev. Jones claimed was a revolutionary act.[5]

Comparable to other religious or social movements, Peoples Temple began to grow and change. Ideological rhetoric moved further away from the original Pentecostal liturgy and more towards a radical Marxist communal message. New religious movements often evolve as membership grows and the leader becomes more empowered. Public awareness, membership, even growth in the leadership contributes to the evolution of a given movement. It is important to analyze and understand Peoples Temple in the context of a new religious movement, rather than a cult organization. Use of the term “cult” encourages biased and negative opinions, as opposed to subjective and analytic ones. Peoples Temple was and will be considered as a new religious movement that experienced change and eventual devolution into a harmful organization that engaged in seemingly, but not necessarily, cult behavior.

Emerging during a time of intense racial segregation, as well as many burgeoning new religions, Peoples Temple attempted to create a colorblind, communal utopia. Rev. Jones was the harbinger of racial freedom, integrating not only his congregation, but his family. He attempted to revolutionize and radicalize race relations, religion, and socialism. The progressive nature of his message coupled with an integrated membership provided Rev. Jones with an adequate platform. Additionally, Rev. Jones’ multicultural family lent crucial legitimacy to his integrationist, equal rights message. As the adoptive father of both African-American and Asian-American children, his dedication could not be questioned.

To begin, this thesis will provide a brief background to both new religious movements and cults, as well as showing the importance of making an academic distinction between the two terms. Peoples Temple is often referred to as both, however this thesis will only consider Peoples Temple as a legitimate new religious movement. Chapter I will provide a background to Rev. Jones, focusing specifically on his introduction to religion. The chapter will then examine the creation and development of Peoples Temple as a Pentecostal church in Indiana.

Chapter II will follow both the ideological and geographic shift of the Peoples Temple. As the group migrated to California, Rev. Jones shifted his ideological rhetoric away from traditional evangelical theology and more towards socialism. The final chapter, Chapter III, will examine Peoples Temple in Guyana. During this phase of the movement, almost all traditional religious constructs were gone and Rev. Jones encouraged extreme socialist ideas.

Most literature focuses specifically on the time in Guyana, however this thesis will only examine the changing theological rhetoric, rather than proclaiming Peoples Temple as a cult organization. Specifically, the author hopes to provide insight into the purposeful transformation of Peoples Temple from a new religious movement into an aggressive agricultural commune located in South America. This thesis will examine the process of radicalization of Peoples Temple, looking at both the internal development of doctrines and the external context of the broader socio-political climate. Each phase of the movement, as well as their corresponding doctrines, will be analyzed, to show the progression from Evangelical Pentecostalism to extreme communalism.

NEW RELIGIOUS MOVEMENT OR CULT?

The line between new religious movement and cult is frequently blurred and highly contested. While the terms are often used interchangeably, most scholars believe that the use of cult creates a negatively charged bias against any movement described in that manner. For the purpose of this paper, Peoples Temple will be referred to as a new religious movement unless the word “cult” is used in a direct quote.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the United States experienced a surge in new religious movements. A new area of study “arose in the context of the proliferation of countercultural movements…and the initial orientation of area of study was heavily influenced by the cult controversy of that era.”[6] A major goal of this new field was to provide an academic definition for these new and continually developing movements. The objective was to avoid harsh criticism or a priori judgment of a particular new religious movement, but to provide an academic understanding and applications for society as a whole.

A new religious movement is defined as a religious community or spiritual group of modern, for the time of development, origins. They are markedly different from existing religions but are generally assigned to the fringe of dominant religious culture.[7] Several current religious traditions, such as The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, began as relatively small new religious movement. As such religious movements become more popular and more mainstream, they are generally referred to as alternative religions. Scholar Eileen Barker notes that “no new religion would be regarded in quite the same light or treated in quite the same way after Jonestown.”[8] Rather than utilizing Peoples Temple as a litmus test for emerging new religions, academics should understand the theological evolution, or devolution, of the movement.

On the other hand, a cult is defined as a deviant religious organization with novel beliefs and practices. Cults are often without a clear and consistent message. These groups are often spontaneous and short-lived. Cult is more often used to provide psychological or sociological analysis of a perceived deviant new religious movement. David Chidester, religion scholar and author, notes that, “The very notion of ‘cult’ seems to lead us to extremes.”[9] Employing the term “cult” with regards to Peoples Temple marginalizes the members and ignores the theological foundation of the movement.

The distinction between a new religious movement and cult is integral to this thesis. Most available literature focuses solely on the tragic end of Peoples Temple. The ideological constructs present in Guyana are comparable with cult behavior and norms, but Peoples Temple did not emerge in that manner and certainly did not intend to evolve in that direction. By continually referring to Peoples Temple as a cult, scholars brand the movement as wholly deviant and disrespect both the original goals and those individuals who lost their lives. When Rev. Jones established Peoples Temple, it was characteristic of an authentic new religion, drawing on inspiration from Pentecostal teachings. As Peoples Temple grew in size and influence, Rev. Jones began to incorporate various religious and social doctrinal concepts. In this sphere, Peoples Temple meets the criteria for classification as a new religious movement.

Birth of the Reverend

“Reverend Jones described Peoples Temple as a church whose ‘door is open so wide that all races, creeds, and colors find a hearty welcome to come in, relax, meditate, and worship God.’”[10]

James Warren Jones was born 13 May 1931 in Lynn, a small town in east-central Indiana. His mother, Lynetta, was considered to be progressive and crude compared to most women of the time period. Serving as the primary breadwinner for the family, Lynetta openly smoked, drank, swore, and wore pants almost every place she frequented. His father James, on the other hand, was ill and could not work. Instead, Mr. Jones visited the town pool hall on a near-daily basis. He was openly and violently racist; once, when his son brought home a young African-American boy, Mr. Jones became aggressive and threatened both children. Neither parent harbored any religious tendencies and often neglected their young son.[11]

As a result of their neglect, and the lack of any brothers or sisters, young Jimmy, as he was known then, was starved for attention and acceptance. He searched for meaning and love, sampling a variety of religions present in Indiana. Thanks to his neighbor Mrs. Myrtle Kennedy, the young boy found his place in the church. Mrs. Kennedy saw that the boy had a gift for speaking the word of God and fashioned herself as “Jimmy’s spiritual mother.”[12] Jimmy’s search for familial acceptance and love resulted in his visiting all the religious houses present in Lynn. He attended services frequently with Mrs. Kennedy, but also ventured out on his own. Eventually, Jimmy found his place at Gospel Tabernacle, a radical Pentecostal church located on the edge of town.[13]

The already-marginalized Pentecostals represented the family and acceptance he was looking for. Jimmy was awed by the power the preacher held over his followers. Possibly, due to his need for a strong father figure, Jimmy saw the man as being a spiritual father for himself and the congregation.[14] As a peculiar and solitary young child, Jimmy felt drawn to the enthusiastic and eccentric worship style of the Pentecostal church. Rev. Jones remarked later that he “joined a Pentecostal Church, the most extreme Pentecostal Church… because they were the most despised. They were the rejects of the community. I found immediate acceptance… about as much love as I could interpret.”[15] At Gospel Tabernacle, his peculiarities were seen as a gift from God; here, Jimmy no longer felt marginalized or ostracized.

Pentecostal worship is marked by the presence of a charismatic leader. According to Charles Lippy, “charismatic characterizes any Christian in any church tradition who exercises one of the post conversion gifts of the Holy Spirit.”[16] These gifts include prophecy, healing, miracles, discernment of the spirit, and glossolalia, or speaking in tongues. One who experiences any of these gifts is considered to be blessed by God. Pentecostals are also noted for their enthusiastic worship style. It is not uncommon to find worshippers speaking in tongues, falling to their knees, crying, yelling, or being healed by faith. Due to their enthusiastic and peculiar worship and belief styles, “Pentecostalism has always belonged to the marginalized.”[17] Because Jimmy felt marginalized at home and by his peers, it is not difficult to understand why the Pentecostal church was appealing.

Even at a young age, Jimmy was fascinated with religion and death. He conducted religious services for neighborhood children and friends. After watching the Pentecostal preacher, Jimmy “set up a little church that he called ‘God’s House’ in the loft above the family garage.”[18] In addition to proselytizing area children, Jimmy conducted funeral services for deceased animals. The services were peculiar and very ritualistic. One childhood friend believed that Jimmy had killed a cat, so that he could perform an elaborate burial service for the animal.[19] Whether or not the killing actually happened is subject to debate, but what is evident is that Jimmy had a desire to completely engage in religion.

As he grew older, Jimmy began to hitchhike into nearby Richmond, dressed in a white robe fashioned from a bed sheet. There he would preach from street corners, drawing small crowds of both black and white listeners. “As he stood on that street corner waving the Good Book, he stressed the need for brotherhood and tied the message to the written word of God.”[20] Prior to his street-corner preaching, Jimmy became fascinated with socialism and charismatic dictatorship during World War II.[21] He was intrigued by the socialist constructs, but knew that they would never be appealing to a majority of Indiana residents, unless presented in a familiar manner. This intricate fusion of a socialist message cloaked in religious rhetoric would define the future Rev. Jones and Peoples Temple for many years to come.

During the early 1950s, Jim – the name he now preferred – worked as an orderly at a hospital in Richmond. Here he met a young nurse, Marceline Baldwin. “Marceline could not help but be drawn to the pure energy of young Jones. What she saw was a contagious personality trumpeting a wonderful dream…of making a better world.”[22] Jim’s soon-to-be wife saw exactly what he projected to the rest of the world: a tenacious young man striving to combat racial and social injustices. Shortly after their marriage, Jim announced that he would be joining the ministry, believing “it would fulfill his personal need to lead people and would provide a forum, not to say a cover, for his controversial views.”[23] With religion, Jim would finally have an acceptable and far-reaching platform through which he could spread his socialist and integrationist message.

Initially, Rev. Jones began studying as a Methodist preacher. In 1952, Jones became a student minister at the Somerset Methodist Church in Indianapolis.[24] However, just as he had done as a child, he would study a variety of religious styles, before settling on the eccentric and enthusiastic Pentecostal. While the Methodist social creed was heavily representative of his own social beliefs, his preaching style remained strongly influenced by Pentecostalism.[25] The Pentecostal worship, combined with faith healing and an emphasis on social outreach, suited Rev. Jones. The power he enjoyed over the congregation was important for the young man who had felt like an outsider most of his childhood.

“Pentecostalism came to represent both style and substance for Jim Jones: a style of vibrant, expressive worship, manifestation of the spirit, and faith-healing miracles; a substance, based on Acts 4:34-35, of sharing, cooperation, and mutual support.”[26] The enthusiastic worship style, as well as the complete devotion to the preacher, suited Rev. Jones’ liturgical needs. He needed an adequate platform from which to spread his gospel of socialism and racial integration. Pentecostalism provided him with the best opportunity to gather and convert followers.

Additionally, the faith-healing aspects of Pentecostalism allowed Rev. Jones to convince his congregation that he truly was touched by the spirit and that his message was the true word. By supporting his goal of cooperative socialism with biblical sources, Rev. Jones legitimized the message for both his religious and political followers. Eventually, religion would become simply the presentation; once they were there, the package he presented was much more. With the Pentecostal platform, Rev. Jones could preach that everyone had a purpose, ensuring that everyone felt special.

Peoples Temple Full Gospel Church

As a student minister, Rev. Jones attempted to integrate the church by openly welcoming African American members of the community. Indiana during the 1950s was home to strong racist sentiments and the national headquarters of the Ku Klux Klan.[27] While Rev. Jones attempted to combat these feelings, “It was one thing for white believers to nod in passive agreement when their preacher said that all humans were created equal in the eyes of God; it was quite another to stand shoulder to shoulder with a black person, sharing a hymnal.”[28] After several families left the church, board members decided not to invite the young student minister back to lead their congregation. Frustrated with the hypocrisy of the religious institutions in Indiana, Rev. Jones established his own church in 1954.

Peoples Temple Full Gospel Church was a traditional Pentecostal church. Rev. Jones incorporated the main tenants of Pentecostalism into his sermons. These included faith healings, prophecy, speaking in tongues, and miracles. Sermons “reiterated familiar themes in evangelical Christianity: creation and fall, sin and redemption, personal evangelism.”[29] Central to the message was acceptance of all individuals, regardless of race. Rev. Jones intended to bring individuals to the church by Pentecostalism, but hoped to keep them there to hear his message of racial equality. However, as the church grew in numbers, Rev. Jones began to adapt the religious worldview of his particular variety of Pentecostalism.

Because the initial church was based predominantly around the Pentecostal worship style, faith healings were integral to each meeting. The “healing ceremonies were glorious spectacles” but the amateur sleight of hand used to execute them were fairly obvious.[30] However, most of the loyal followers did not mind the deception, simply because Rev. Jones’ message was so powerful. The healings served to fulfill the church’s designation as a Pentecostal establishment, as well as to encourage more individuals to attend the ceremonies.

Rev. Jones often employed a call-and-response worship style. His oratorical cadence varied, as he would draw the audience in. He would vacillate between slow and soft-spoken, then launch into a booming, fervent monologue. Asking his listeners to respond with cheers of “Amen,” Rev. Jones would find the enthusiasm to continue with his sermon. This call-and-response style of preaching resonated strongly with the predominantly African-American congregation. The enthusiastic back and forth liturgical dialogue between congregation and preacher is often found within the Baptist denominations, to which African-Americans largely belong.

Peoples Temple Full Gospel Church was a unique blend of religion and socio-political teachings. Rev. Jones emphasized the social gospel in both his sermons and his actions. The social gospel was a Protestant movement that attempted to use Christianity as a means of solving social problems. Urban ministry and extreme social reform through various outreach programs are key aspects of the social gospel. Peoples Temple drew upon this and established nursing homes, drug rehabilitation programs, soup kitchens, adult education classes, and free legal clinics.[31] These actions are generally associated with “progressive middle-class Protestant denominations” but show how Rev. Jones created a revolutionary blend of religion and social action.[32]

Peoples Temple Full Gospel Church grew rapidly and was supported financially by Jones’ own non-profit organization called Wings of Deliverance. The organization helped establish the programs in accordance with the social gospel aspect of the church. “During this period, Jones and church members knocked on the door of every black home in Indianapolis, working hard to build an interracial ministry.”[33] Rev. Jones insisted that black members were treated equally, inviting them into his home and ensuring that they always had front-row seats for every sermon. One of Rev. Jones’ associate ministers noted that “Jones was hated and despised by some people, particularly in the white community.”[34] His integrationist message, as well as actively integrating the church, broke new ground in race relations.

The late 1950s was marked by a shift in ideology after Rev. Jones was invited to meet with Father Divine. Father Divine, leader of the Peace Movement, represented “an exemplary model of the marriage of religion and racial equality.”[35] The Peace Movement encouraged racial integration and communal living. Father Divine fashioned himself as a prophet, highlighting the importance of self-help, communal meals, and black capitalism.[36]

Father Divine attempted to create a working model of an integrated society. In one sermon, he preached about the importance of harmony in religion and life, unity, the power of positive thinking, and most significantly, the need to transcend race.

I mention this because as mortality in its egotistic ways of expression rises and manifests itself in the mortal minded people as critics, there and then is the time I shall rise on the hearts and minds of mend as I have never done. Oh it is indeed Wonderful! I shall bring them from every so-called tried, from every so-called nation, from every so-called language and every so-called people. I shall bring them to the recognition of GOD in a Body, and they as well as you shall recognize their FATHER.[37]

This passage is of note because Father Divine suggests that he is God, in corporeal form. Rev. Jones would adopt many of Divine’s techniques to his own repertoire, but one of the most significant aspects Jones employs is the concept of himself as the physical manifestation of God. Father Divine often “claimed to be God in an equivocal sort of way.”[38] Rev. Jones’ grandiose claims would slowly escalate; after returning from his encounter, Rev. Jones “encouraged his congregation to call him “Father,” as Divine’s followers called him.”[39] Establishing himself as a God-like figure would allow Jones to shape his doctrine in various ways.

While the traditional Pentecostal sermons continued to draw members, Rev. Jones believed that the faith healings and enthusiastic worship encouraged members to focus too strongly on the religious aspects of his message. After the meeting with Father Divine, Jones became convinced that communal living and socialism were the best methods with which to combat growing racism. The late 1950s marked the start of his ideological shift and the refocusing of his message. Rather than rely solely on religious rhetoric and practices, Rev. Jones would increasingly incorporate more socialist messages into the Temple.

In 1959, Rev. Jones delivered a landmark sermon where he presented his new style, consisting of a fiery oratorical styles and progressive subject matter that would dominate Peoples Temple for years. Along with the inclusion of an us-versus-them message, Rev. Jones “warned his listeners to wake up for the healings coming. ‘Either you endure sound doctrine when I preach it or you don’t hear it.’”[40] While Rev. Jones referred to faith healings, he was also speaking of a metaphorical healing of society. This societal healing would only be achieved by adherence to the teachings and practices of Peoples Temple.

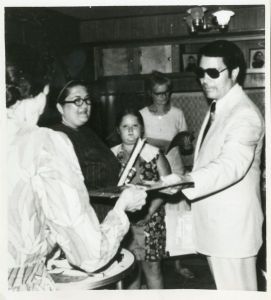

Peoples Temple increased its community services, and the Jones family became a living example of the message. After the birth of their first, and only, natural born son, the couple became the first white family in Indiana to adopt a black child.[41] Rev. Jones and Marceline would create their own rainbow family, showing the world that integration, acceptance, and love for all races was possible. “At the pulpit, he could now relate his personal experiences with racism and thus gain credibility with his increasingly dark-skinned flock.”[42] If the young minister practiced what he was preaching, then it would be difficult for anyone to doubt his authenticity and passion.

Rev. Jones’ message of racial equality, as well as his social and religious ideology, spread well beyond the walls of Peoples Temple Full Gospel Church. Drawing upon Father Divine’s influence, members began to actively protest racism in the area. The congregation would knock on doors in the African-American neighborhoods, spreading the word of a truly integrated church. By implementing Father Divine and the Peace Mission’s techniques and practices, Rev. Jones begins to move more towards the socialism that would define Peoples Temple. This key shift in ideological practices and principles signifies that start of Rev. Jones’ us-versus-them rhetoric that would escalate over the years.

Rev. Jones was increasing his socialist tendencies within the church, while Peoples Temple projected an outward image of a wholesome, albeit progressive, evangelical church. “By 1960, Peoples Temple had affiliated with the Disciples [of Christ], and in 1964 Jones was officially ordained a minister.”[43] Prior to this, Peoples Temple was not supported by an overarching ecclesiastical authority. The choice of Disciples of Christ is fitting; the church is democratic oriented and aims for achieving wholeness. Historically, women and minorities played a strong role within the church, mirroring the integrationist aims of Peoples Temple.[44] Minorities were featured prominently, and women were among the inner circle that helped run the church.

As a recognized Disciples of Christ church, Peoples Temple was required to perform two rituals – full immersion baptism and communal meals.[45] Communal meals, as described in the Book of Acts, were already a key part of Rev. Jones’ social gospel. Religiously, the purpose of communal meals is to celebrate and reenact the Lord’s Supper. Peoples Temple members frequently ate together, as well as provided community meals for the homeless and less fortunate. Full immersion baptism is a ritual experience, used to signify the individual fully accepting Jesus Christ as their Lord and Savior. For Rev. Jones, baptism, like faith healing, was performed only to satisfy the needs of the more religious members. Rev. Jones utilized traditional religious ritual as a method of drawing religious followers; however, once they were captivated by the movement, he would emphasize the socialist message over the religious.

Disciples of Christ, like Peoples Temple, advocates humanitarian and social outreach. As a part of the Restorationist movement, Disciples of Christ attempted to return religion to apostolic Christianity. Under this, followers believe to legitimately proclaim the message of God. Essentially, they profess and believe to be the only Christian denomination that represents the genuine word of God. The goal is to speak and follow the Bible as it is written. There is no room for excess interpretation, and where the Bible is silent, followers are silent. Additionally, followers are encouraged to actively engage in selfless acts of community service. Giving back to those less fortunate mirrors the attempts by Christ to spread goodwill and redeem the sins of mankind. These religious concepts allowed Rev. Jones to seamlessly blend his socialist message into the religious doctrine of the evangelical church.

Holiness and the holiness movement were also significant contributors to the early Christian message of Peoples Temple. Traditionally, the holiness movement believes that individuals can achieve sanctification if they accept Christ as their personal savior. Rev. Jones incorporates this belief structure, replacing himself as the Christ figure. Technically, Peoples Temple does not completely adhere to traditional Christian dogmatic practices because Jesus Christ is not necessary for the salvation experience. However, the early church located in Indiana experienced and practiced more traditional Christianity than any other geographical incarnation. “At one time, the Holiness movement concentrated much of its attention on social issues and public morality.”[46] Peoples Temple adheres strongly to the public service and communal ministry; providing service for those less fortunate would break down socio-economic and racial boundaries.

Through the use of faith healing, baptism, glossolalia, and strong biblical overtones, Rev. Jones was able to address each religious member in the crowd. For the non-religious members, Jones would include his socialist and integrationist message. Peoples Temple began to move “towards communism under the guise of Christian communalism.”[47] Fusing Marxist teachings with scripture allowed Rev. Jones to convince his religious and non-religious followers that religious communalism was the best way to combat racial segregation.

Eventually Rev. Jones incorporated apocalyptic millennialist concepts into the theological framework. Millennialists adhere to the belief that the world will be destroyed in an apocalyptic event, wherein all non-believers will perish and the faithful will reign with Jesus Christ. Peoples Temple deviates from this theological construct in two ways. First, the apocalyptic event is not a result of growing secularism but rather heightened racial tensions. Second, the redeemer figure of the Last Judgment is Rev. Jones as opposed to Jesus Christ. These differences are significant because they show how Rev. Jones adapted traditional Christian constructs within the theological rhetoric of Peoples Temple. Rather than adhering to traditional Pentecostal constructs, Rev. Jones created a new movement, one that appealed to a wide spectrum of individuals, from strongly religious to politically active non-believers. As former member Laura Johnston Kohl remarked, “Everyone would get the message they wanted to hear.”[48]

Jones began receiving a series of visions predicting the “impending capitalist apocalypse.”[49] Fearing the worst, Rev. Jones relocated his family to Brazil in the hopes of finding an isolated socialist paradise. For two years, Rev. Jones attempted to establish a commune in the jungles of Brazil, while running Peoples Temple from a distance. Just as he had done as a young child and as a student minister, “Jones explored some of the Brazilian cults,” such as Macumba.[50] The tribal religion is marked by a fusion of traditional cultural aspects and Roman Catholic, European influences.[51]

While in Brazil, Rev. Jones began to move beyond the strict confines of Christianity towards a variety of native religions, going so far as to begin to view himself as a shaman and deity. The transition from preacher and father to prophet and deity was inevitable, considering Rev. Jones’ adoption of Father Divine’s techniques. Father Divine established himself as a God-like figure to his followers, a construct Rev. Jones would attempt to emulate almost immediately. After returning from Brazil, Rev. Jones began to refer to his aura; merely the physical presence of Rev. Jones could heal illness and increase spirituality. This concept is pivotal in new religious movements “to the extent that a movement emanates from a revelatory/mystical experience by the leaders and the leader’s charismatic authority remains the primary internal power base.”[52] Implying that proximity to his aura was directly related to the spiritual experience, Rev. Jones ensured that few members would leave the church.

As a result of the church’s extensive outreach program, coupled with the progressive integrationist mentality of both the leader and members, Rev. Jones was appointed to the Indianapolis Human Rights Commission.[53] Peoples Temple was cited as the quintessential progressive church, one that genuinely practiced and lived Christian ethics. The influence and power of Rev. Jones was overwhelming. During one service he proclaimed, “Don’t worship me, become like me.”[54] Success of the social message was not without some negative responses. Rev. Jones, utilizing the us-versus-them rhetoric adopted from Father Divine, began to speak of persecution against members.

The perceived persecution of Peoples Temple reached a peak when the property was vandalized and Rev. Jones claimed to have received death threats.[55] Simultaneously, the rhetoric during services escalated. Almost each sermon drew parallels to the biblical exodus; Peoples Temple was the righteous word of God and they were thusly being persecuted for espousing the truth. Consistent with the apostolic aspects of the religion, Rev. Jones established a parallel between the apostles of Christ and Peoples Temple ministers.[56] Just as Christ’s apostles were persecuted for returning to the true word of God, so would Rev. Jones and his flock be persecuted for living in a true Christian manner.

“In January 1962, Esquire magazine published an article listing the nine safest place in the world to escape thermonuclear blasts and fallout.”[57] Believing that Indianapolis would be annihilated in the ensuing nuclear fallout, Rev. Jones cautioned his followers that an exodus west was necessary. Again drawing on biblical constructs, Jones creates legitimacy for the religious aspects of Peoples Temple. Members espousing such beliefs are portrayed as modern Israelites, persecuted for their progressive integrationist Pentecostalism. Because the trip to Brazil proved unfruitful, Rev. Jones decided to look westward.

Peoples Temple in Indiana was a unique blend of evangelical Christianity and socialist thought. During this time, Rev. Jones studied a variety of religions, seeking to incorporate as many theological influences as possible into his unique movement. Originating as a traditional evangelical Pentecostal church, Peoples Temple gradually but steadily evolved into a progressive social movement with religious foundations. Through the use of standard theological practices, such as faith healing, glossolalia, and enthusiastic worship services, Rev. Jones was able to draw members from a variety of religious backgrounds.

The strong integrationist and increasingly socialist message was appealing to members and non-members alike. Rev. Jones and his congregation were lauded for their attempts to reform and combat racism in conservative Indiana. The Jones’ adopted an African-American child; Marceline Jones was often called names and spat upon when in public with her adopted child.[58] Yet these acts of aggression strengthened the resolve of each member in the congregation. Proof that their beliefs and social outreach impacted the Indianapolis community, Rev. Jones and Peoples Temple redoubled their efforts. Soup kitchens, shelters, and nursing homes were opened. Classes and legal assistance were offered to the poor, free of charge. Resources were pooled into a communal offering, to be shared by all members.

However, as a result of growing racial and political tensions in both Indiana and the rest of the United States, Rev. Jones began experiencing apocalyptic visions. In these visions, thermonuclear war would result in the complete eradication of the Midwestern United States. Apocalyptic millennialist theology gradually began to influence Peoples Temple. Fearing for the safety of both his members and his message, Rev. Jones began to urge his congregation to embark on a westward exodus. In northern California, Rev. Jones would expand his ministry, increase his social and political message, and fully develop the theological worldview that would define Peoples Temple.

The Exodus – California Dreaming

“If Indianapolis represented the conservative heartland, then California signified the progressive frontier.”[59]

In July 1965, about 140 Peoples Temple members loaded their worldly possessions into their cars and began the migration to California. Roughly half of the group was Caucasian families, the other half African-American. Believing that thermonuclear war was imminent, Rev. Jones had convinced a majority of his congregation to flee the conservative and bigoted Indiana. The impending war, according to Rev. Jones, was a result of growing racial tensions in the United States. Peoples Temple was meant to serve as an example of the perfect socialist utopia, masked as a religion. California, specifically Ukiah, would act as a natural barrier, protecting the congregants from nuclear fallout. Rev. Jones was convinced that the liberal landscape of California would be provide the perfect home for the burgeoning religious and social movement.

After the Exodus, Peoples Temple began searching for a church where they could worship. However, California was not the idyllic refuge Rev. Jones had envisioned. Members were turned away from various churches and some African-American members were refused apartments. “During an outing to swim in Lake Mendocino, local bigots baited the group, calling them ‘niggers’ and ‘nigger lovers.’”[60] Due to the negative experiences members had with local Californians, Peoples Temple members became increasingly suspicious of non-members. This suspicious attitude would manifest in recruitment and member initiation practices.

After the Exodus, Peoples Temple began searching for a church where they could worship. However, California was not the idyllic refuge Rev. Jones had envisioned. Members were turned away from various churches and some African-American members were refused apartments. “During an outing to swim in Lake Mendocino, local bigots baited the group, calling them ‘niggers’ and ‘nigger lovers.’”[60] Due to the negative experiences members had with local Californians, Peoples Temple members became increasingly suspicious of non-members. This suspicious attitude would manifest in recruitment and member initiation practices.

Eventually Rev. Jones bought land in Redwood Valley. There they built a space that served as church, community center, farm, commune and home to the Jones family. “The Temple was a large wooden building…There were floor-to-ceiling windows and a beautiful stained-glass one behind the podium with a dove in flight.”[61] Community members also built a swimming pool in the center of the building. The pool served as a recreational tool for the group and was also where Rev. Jones performed baptisms. The land and community they created in Ukiah mirrored the socialist utopian message. Rev. Jones sought to show that individuals of all races could live together in harmony.

The idyllic, isolated location of the Ukiah church was the perfect choice for the burgeoning movement. “World-rejecting/transformative movements are organized as collectives, families, and communes…Since these movements are collectivist in organization, maintain strong separation from conventional society, and diminish individuality, movement leaders are more likely to exhibit strong charisma claims.”[62] These types of new religious movements tend to focus energy on maintaining the righteousness of information provided solely within the group hierarchy. Members often engaged in aggressive and active recruitment, while at the same time maintaining a high level of skepticism of outside members. Peoples Temple California encouraged a strong separation from society but maintained a reliance on aggressive recruitment techniques to continue membership growth. The isolation of members allowed for the development of a new theological outline, one that would continue to be hypocritical with regards to Christianity.

The move to California marked a substantial dogmatic shift. During this time Peoples Temple became more of a social and political action movement. Members increased their outreach programs and often actively campaigned on the behalf of local politicians. According to a member who joined Peoples Temple in California:

There was a great divide at first because most of the new California members were progressive atheists, non-dogmatic Christians, Buddhists, or New Age types. Even the Baptists who joined from San Francisco were more progressive than the group that Jim had brought from the Midwest. But Jim soon brought us all together in one cohesive group, his core group of supporters. Later on, more traditional Christians joined in once the ministry started visiting San Francisco, Los Angeles, Seattle, and other smaller cities.[63]

Naturally, Peoples Temple attracted a variety of social activists and progressive individuals seeking an alternative to traditional groups.

The ideological refocusing of Peoples Temple occurred gradually over a period of several years. Services still included the charismatic flair of early evangelical Pentecostal services. However, the dogmatic message became increasingly politically and socially motivated. Rather than focusing specifically on the Bible and belief in God, Rev. Jones espoused the idea of “God Almighty Socialism.”[64] Through actively living a communal lifestyle, serving the less fortunate, and devoting one’s life to the Temple, a member could achieve whatever salvation they sought. “The religious history of California is filled with stories of maverick religious leaders taking their people outside the boundaries of their traditions general practice, sometimes dangerously.”[65] In order for the transition to be palatable, Rev. Jones would need to shift the doctrine and rhetoric gradually.

“Apart from the civil rights movement, the 1960s promoted a mood of openness that encouraged people to respect diversity and thus to move freely among different lifestyles and worldviews.”[66] In other words, the political and social atmosphere of the 1960s explains how Peoples Temple and Rev. Jones could push a socialist agenda without total religious cover. Religion tinged with socialism became a socialist revolution tinged with religion. California represented the progressive, revolutionary landscape, and Rev. Jones was the apostolic prophet sent to combat racism, sexism, ageism, and elitism through the living gospel of socialism.

By 1968, “Peoples Temple was granted official standing within the Christian Church, Disciples of Christ, Northern California-Nevada region.”[67] Continuing with the traditional Pentecostal liturgical styles established in Indiana, services were enthusiastic and prominently featured healings. One member remarked, “I watched as the young people began dancing around, happy, comfortable, not the least bit self-conscious.”[68] Sermons continued in the call-and-response style. The “magnificent interracial and intergenerational choir would sing the most exhilarating hymns and songs. Many of the songs were original, and many were re-written to reflect the Temple philosophy.”[69] Congregants would mingle, clap, and sing with members new and old. After the congregation was sufficiently enthused, Rev. Jones would walk towards the pulpit. The atmosphere of most services was electric.[70]

The implementation of the communal socialist concepts began much as they had in Indiana. Members were encouraged to donate portions of their paychecks during the weekly meetings. Those who did not work were asked to provide any money they had or to volunteer their time. The elderly, most of whom lived in Temple-run nursing homes, sold their houses and turned over Social Security checks. These individuals were more than willing to give everything they had to the Temple, because the Temple provided absolutely everything they needed. Temple homes were luxuriously furnished, each resident had their own room, and Rev. Jones ensured that they were constantly looked after.[71]

Younger members were encouraged to live in Temple-sponsored dorms. The communal housing reduced the amount of money they would spend and ensured they were being indoctrinated with the Temple message around the clock. Additionally, “the college students began some paramilitary training to prepare for the post-nuclear world. [They] jogged every night, practiced field navigation using a compass and flashlight, studied guerilla tactics, memorized portions of Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto, and sang ‘The Internationale’ at the close of each evening devotion.”[72] Rejection of Christianity increased and was replaced by Marxist and socialist training under the guise of apocalyptic millennialist beliefs. Yet, it would be several more years before Rev. Jones openly rejected the Bible and Christian theology. The younger members were presented with the socialist message before most of the congregation; this was due to the fact that the majority of them had rejected religion and joined the Temple based upon its social welfare and communal message.

However, because many members, mostly the older African-American congregants, still had strong religious beliefs, Rev. Jones continued to employ traditional religious rituals in meetings. Elaborate healing ceremonies occurred at the end of each meeting. “Over the years, many people joined the Temple so that their loved ones or they would be cured of an illness or protected from another sort of evil. Jim was seen as a protector, and a lot of people felt themselves to be in danger of illness of violence.”[73] During these ceremonies, individuals would expel cancerous growths, either in front of the congregation or privately in the restrooms. Afterwards, Marceline Jones would present the growths to the congregation while they clapped, sang, and prayed.[74] Rev. Jones was able to recruit a wide spectrum of followers essentially due to the fact he gave them an opportunity to be a part of something bigger than themselves. Religious aspects, including healings, were a key facet of the conversion process.

Another important evangelical construct that Rev. Jones continued with was his gift of prophecy. However, like many so-called religious prophets before him, Rev. Jones utilized his loyal inner circle members to gather information. “Others dug through trash bins collecting personal data for his supposed revelations. They were crafty and brazen. Inside, [a Temple member would] take an inventory of the residence…and pass the information along to Jones.”[75] In addition, members would be planted around the audience, secretly passing notecards with information gathered on new members attending the meetings. Those who participated actively in his deceit did so believing wholeheartedly in his message of apostolic socialism. Realizing the need to capture and maintain the belief of the more religious members, “those who stayed accepted the fraudulence to receive the message, one that became a combustible mixture of sacrilege and socialism.”[76]

During the late 1960s, several members, including Rev. Jones and his wife, were working in various social outreach sectors. Marceline Jones was employed as a social worker. Two loyal members, sisters Hyacinth Thrash and Zipporah Edwards, ran a Temple-funded nursing home. Other members worked as teachers, nurses, social workers, secretaries, and construction workers. Rev. Jones taught low-income middle school students, using the opportunity to recruit more members. The message of serving one’s community became more than a message; apostolic socialism and community activism became a way of life.[77]

Just as he would during church services, Rev. Jones would not rely on provided textbooks in his classroom. Rather, he preferred to moderate heated discussions between students and espouse his socialist beliefs.[78] This reliance on personal anecdotes and reiteration of outside negative forces is a key building block of new religious movements. “As a way of reining in freedom of choice, a new emphasis was also placed on the dangers of external constraints, such as those imposed explicitly by government…and freedom of choice meant exposing oneself to alternative experiences that would help develop these voices.”[79] In this, Rev. Jones ensures that the perceived free choice made by members is favorable for the church. This model encourages freedom of choice within the church structure by suggesting restriction by and persecution from non-members. Rev. Jones provided the only information members needed, while simultaneously suggesting that all outsiders were wrong or misinformed bigots.

God is Love, Love is Socialism

The years in California represented the complete construction of Peoples Temple theological outline. The construct consists with four key points: (1) The Skygod does not exist, (2) genuine God is in the form of the divine principle, (3) God is represented by a physical presence, i.e., Rev. Jones, and (4) deification is possible for all members.[80] These theological principles were only vaguely developed in Indiana; however, the rapid increase in membership, coupled with the isolation of members, provided Rev. Jones with an adequate platform to finally complete his vision for Peoples Temple. “In California, he shed Midwestern convention and embraced the Golden State’s emphasis on sensation.”[81] The migration to California allowed Rev. Jones to adapt, change, reinterpret, and reinvent the dogma of Peoples Temple.

All four points of the theological outline serve to discredit traditional Christianity and the Bible. In arguing that the Skygod does not exist, Rev. Jones forces his congregants to search for a replacement. The other-worldly God creature, in the eyes of Rev. Jones, was responsible for the suffering of mankind. The “blind and superstitious worship of Skygods, spooks, or unknown gods [is] intrinsically linked with acquiescence to tyranny.”[82] Rev. Jones employed the use of such negative rhetoric in several sermons. Often he argued that belief in such a creator was illogical, and that such worship resulted in control of the believer. In 1974, he went so far as to ask his congregants, “And you believe in God?”[83] The rejection of traditional Gods or God-like figures is commonplace in new religious movements; the leader wants and needs to be the quintessential figure literally and spiritually for his or her followers.

The logical next step in the rejection of an ethereal God is to replace said God with a physical figure. According to Chidester, Rev. Jones first employed the gnostic redeemer myth before completely rejecting God all together. In this, Rev. Jones notes that the Skygod had forsaken all humans, and he alone would save them from damnation. Former member Deborah Layton said, “Jim explained to me how he and I needed to help the poor, how those who remained drugged with the opiate of religion had to be brought into enlightenment – socialism.”[84] As the physical manifestation of God, Rev. Jones could save, feed, protect, and liberate his flock.[85]

I’ve sincerely and conscientiously not only attempted to prove, but I have proven that you cannot base your faith upon the Bible. Did you get what I said here tonight? You cannot do it. You can’t do it. If you have any doubts about that, I’d hit the floor. I wouldn’t be hypocritical about it, I’d get it out. And you’ll not find anyone with the para-psychological, extra-dimensional, the paranormal, the ESP, whatever you wish to call it, the pre-cognitive, the extra-terrestrial, or paranormal, it makes no difference what you name it, para-psychological, as I said, or the gifts of the Spirit, you’ll find no one that has them developed on this continent to this intensity.[86]

The previous quote is from a sermon given by Rev. Jones in 1972. This specific excerpt is of note for several reasons. In it, Rev. Jones implies that he is the only human on the continent given the power to understand and discern the fallacies of the Bible. However, he does not completely reject the religious, as he names the “gifts of the Spirit” as one possible source for his power. These gifts are prevalent in the Pentecostal faith and something he claimed to have had while establishing his early congregation in Indiana. The Bible, for Rev. Jones, represents nothing more than a set of stories utilized by religious leaders. Faith cannot be found in the Bible or in God; the faith for Peoples Temple can be found in the church. God is manifest in corporeal form as Rev. Jones.

Unfortunately for Rev. Jones, his rejection of the Bible and traditional Christianity would not be consistent or total until the movement’s final relocation towards the end of the 1970s. In fact, he needed Christian theological constructs to expand the doctrine of Peoples Temple. Jesus Christ, he noted, represented the corporeal form of God on earth, sent to suffer for the sins of humanity. By arguing for the corporality of God, Rev. Jones reiterates traditional Christian theology.[87] Rev. Jones did not wish to repent for the sins of mankind, but rather wished to liberate and save mankind through the living example of socialism.

Rev. Jones began to incorporate more Christian themes into his own origin story, claiming that he was born via Immaculate Conception by a more evolved celestial body. The combination of Christianity and celestial bodies was a common theme of new religious movements during the time.[88] In conjunction with proclaiming his other-worldly origins, Rev. Jones went so far as to claim that the source of religion was celestial.

But there’s much higher developments than this. But there no planet out there that’s got dominion over all of these forces in life. And I think some people coming up with theories now that I’ve said a long time ago, that lot of the stuff they got in the Bible was just contact with an outer world. But you won’t get contact again, in that mechanical contact, you won’t be lucky enough to get it, because [of] the long time that it takes to get here.[89]

The inclusion of non-Christian theological constructs is interesting, but reflects Rev. Jones’ growing desire to introduce new themes to his congregation. The more bizarre some of the concepts appeared, perhaps attempting a communal socialist utopia would seem ordinary, if not logical. Celestial themes would appear infrequently; eventually Rev. Jones would abandon the construct entirely.

During one service, Rev. Jones argued the importance of sharing communally with those in the church, proclaiming, “When one was not sharing, we would be touched with a fuse of their infirmities and would bear it and would be happy to share whatever we had and possessed to the good and the welfare of every other person. I’m saying a hard saying that’ll cause many of you to wonder whether you’ve come the right way, but now is the time to wonder.”[90] Using Christian terminology throughout his sermon, Rev. Jones finds a way to include a small mention of socialist communalism. Instead of making socialism the main topic of the sermon, he is able to support the necessity for the socialist gospel with the biblical gospel.

Gradually, but steadily, Rev. Jones established his platform of social revolution. The purpose of such a revolution, he argued, was to combat the subclassification of persecuted peoples. Under this construct, Rev. Jones attempted to create equality for African-Americans, women, and the poor. This worldview could be accomplished by a lifestyle of communal socialism, wherein no individual was treated differently and all resources were shared. In establishing such a community, bigotry would be abolished and the true meaning of religious would be understood. Divine love would be the only way in which people could honor the life and death of Jesus Christ. Interestingly, Rev. Jones viewed himself as the Christ redeemer figure, however, he faced some challenges admitting this role publicly. Privately, he viewed himself as the central figure, but publicly could not object to those members who still held to Christian theological constructs. Traditional theology broadened the audience Peoples Temple could reach; proclaiming to be a God outright would cause a decline in membership.

Social justice, specifically for African-Americans, was called for based upon the life and teaching of Jesus Christ. Combatting racism was the gospel, however the majority of leadership was comprised of attractive, young, white females. The only prominent figure of color was associate minister Archie Ijames, who served to show prospective members that African-Americans and whites could lead side-by-side without disaster.

Surprisingly, violence was not considered appropriate to combat the perceiving growing injustice. While Peoples Temple admired the goals of the Black Panthers and anti-Vietnam protestors, Rev. Jones felt that utilizing violence only served to discredit the movement. However, behind closed doors, violence was sometimes used to discipline disruptive or argumentative members. It is important to note that this particular form of violence was only observed by key inner circle members, and that the majority of the rank-and-file members were unaware of its occurrence.[91]

More frequently, members willingly assisted in the deception and control of other members, rather than resorting to violence on a mass scale. The rationale behind such actions was that eventually divisions would arise naturally due to group dynamics. As a result, “the staff becomes dependent on the founder for policy directives and for serving as the spiritual center of the movement.”[92] This reliance upon the leader was systematic and deliberate; Rev. Jones had been establishing himself as the ultimate source of knowledge for years through a variety of means.

Former member Deborah Layton recalled being told by a top aide, “‘we all come into the fold ignorant. The longer you stay near Jim’s energy and power, the more you will learn and understand. Right now, you are like a small child, but as you stay and grow you will advance and become enlightened.’ She smiled. “We believe in reincarnation. Jim was Lenin in his last life…’”[93] Here, Rev. Jones has incorporated a central construct of Indian religions with political and social activism. By combining the two, the message of ignorance without his presence becomes more palatable. One cannot be fully reborn into the righteous life of socialism until they accept Peoples Temple and Rev. Jones into their hearts and minds. Again, he includes non-Christian theological concepts into the worldview.

According to the Temple theological’s worldview as established in California, God is principle, principle is love and love is socialism.[94] Under this, Rev. Jones argued that socialism was love, the Bible, and God. Baptism, as required for the Disciples of Christ designation, was performed to give one’s self over to apostolic socialism, rather than Jesus Christ. Rev. Jones served as the “messianic incarnation of socialism.”[95] The unique blend of pseudo-religious constructs with Marxist-Leninist socialism allowed Peoples Temple to attract members as well as praise from area politicians and news outlets. The theology of Peoples Temple was anti-theology in that it promised salvation and liberation, religious concepts, through non-religious means.

Martin Luther King, Jr’s assassination in 1968 shocked the nation. After Dr. King’s death, Rev. Jones argued that the racial war/apocalypse was inevitable. Using the high emotional fragility of the African-American community, Rev. Jones presented the racial utopia of Peoples Temple to mourning individuals. Bringing a majority white group to memorials for Dr. King, Rev. Jones showed poor African-Americans that integration on all levels was indeed possible. The rest of the nation no longer hoped that social activism would change the world, but “the message [of Peoples Temple] was the dream is alive.”[96] Most members wanted to change the world, recruited other individuals who wanted to change the world, and honestly believed that they could accomplish that goal. The politically- and socially-charged environment of the late 1960 and early 1970s provided Rev. Jones and Peoples Temple with a chance to seize opportunity. Essentially, the assassination of a prominent African-American leader gave Rev. Jones a chance to suggest that the race war was imminent and present Peoples Temple as the best alternative to life as most currently knew it.

The various techniques of recruitment were utilized to establish race as his primary platform, as well as to legitimize the message. Activism was central and Rev. Jones ensured that his congregants viewed him as understanding the predicament faced by those of the underclass. During one sermon, Rev. Jones proclaimed “‘When I look at all those unhappy honkies, I’m glad I’m a nigger.’”[97] According to the Peoples Temple worldview, being a “nigger” meant one understood the plight of the underclass; even if one looked white, he or she could possess a black heart. Because Rev. Jones had grown up poor, he possessed a black heart, and thus could be the only one to spread the message.

By the mid-1970s, Peoples Temple had grown to an estimated 5000 members, 80% of whom were African-American.[98] Between 1972 and 1975, Peoples Temple expanded its ministry from Ukiah to Redwood Valley, San Francisco, and Los Angeles in order to accommodate the growing congregation.[99] Members would engage in aggressive recruitment. They spent hours walking in poor African-American neighborhoods, passing out flyers and encouraging people to visit the Temple to hear Rev. Jones speak. Several flyers advertised “Reverend Jones’ miraculous healing powers.”[100] Once again, the image presented to the outside community was one of a traditional, albeit progressive, evangelical Pentecostal church.

Recruitment techniques included other traditional Pentecostal methods. Peoples Temple proselytized using radio and television programs, cross-country revival tours, and religious tracts. The contradiction between the socialist message and religious recruitment methods became wider. Rev. Jones would employ religious methods to recruit followers; “once there, he would work at re-directing them into activism. He wanted a heaven on earth.”[101] Evangelical Pentecostalism was no longer a belief for Rev. Jones and, to an extent, his followers. Religion had become a means to an end. The rejection of Christian theology increased at the same time Christian recruitment methods were aggressively utilized.

Eventually Peoples Temple purchased a fleet of Greyhound buses, eleven in total. Each weekend, members would cram into the buses, ready to spread the word of Peoples Temple in California and across the country. These buses also helped facilitate the development of the satellite churches in the surrounding areas. “The Los Angeles Temple was set up chiefly as a way station and recruitment center. Los Angeles was much bigger than San Francisco and included large black communities in the center city, Watts, Compton, and elsewhere.”[102] Members went to Los Angeles almost every weekend to walk neighborhoods, pass out flyers, and scout prospective new members. These bus trips were done in the style of grand revivals, travelling across the country to cities with prominent African-American populations, under the guise of spreading the word of Rev. Jones’ miraculous faith healings. Houston, Detroit, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Washington D.C were among the top cities frequently visited. In reality, meetings in these cities discussed the merits of socialism and the promise of racial freedom out west.

The charged atmosphere of California and the United States surely aided Peoples Temple in its quest to gather more members. As Peoples Temple scholar and family member to key members of the movement Rebecca Moore notes, “Civil rebellions and antiwar protests in America’s cities provided the backdrop for the rapid expansion of the Temple from rural northern California in the late 1960s to urban San Francisco and Los Angeles in the early- to mid-1970s.”[103] People were seeking for a place to engage in the events of the era; long-time church goers became fed up with the overwhelming hypocrisy; educated middle-class young adults desired an organization wherein they could fulfill their philanthropic pursuits.

As the revolutionary atmosphere heated up, both inside and outside the church, Rev. Jones’ rhetoric began to intensify. He began to portray the “United States as Babylon, the Apocalypse as race and class warfare that would engulf a society trapped in its own hypocrisy.”[104] Drawing upon current events, Rev. Jones would argue that only those living under the guidelines of divine socialism would lead the new world, once the current one destroyed itself. A gender-, race-, and social class-blind society was the salvation for mankind. Activism through social welfare, as well as in the political sphere, granted Peoples Temple vast legitimacy within the community. Members were well-regarded and Rev. Jones became a significant political ally.

Membership increased significantly; individuals such as local deputy District Attorney Timothy Stoen provided legitimacy for Peoples Temple in California.[105] Through Stoen, Rev. Jones was able to connect with local area politicians. Increasing their public outreach and social welfare programs, Peoples Temple also began actively engaging in political affairs. Members were used as campaign volunteers; they knocked on doors, registered people to vote, answered phones, and filled empty chairs at political rallies. The use of members as political assets signifies the important transition from a strictly religious organization into one of social activism.

Support for the idealistic group came from across the country. Peoples Temple and Rev. Jones received letters applauding the group’s efforts from the following: local newspaper columnists, San Francisco and Ukiah police chiefs, then-Governor Ronald Reagan, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, and President Richard Nixon. The overwhelming outpouring of support likely stemmed from the group’s social outreach efforts, as well as member’s outward appearance. “To build a positive image, Jones required his group to be well-groomed and clean cut, to register to vote and to be model citizens.”[106] Scholars believe that this was to avoid drawing suspicion to questionable activities, but the outward presentation follows points laid out in Rev. Jones’ social gospel. However, there is no question that the outward appearance helped their image and recruitment, as well as Rev. Jones’ political clout.

Not only were the members convincing Californians of the benevolence and social efficacy of Peoples Temple. “Jones built peace treaties and alliances across the political spectrum, and called in political debts with the aggression of a backroom power broker.”[107] The political connections granted Rev. Jones a little more freedom in expansion and provided him with legitimacy within the community. No matter what strange rumors some people heard, they could be brushed aside due to his personal connections and the reputation of the Temple.

During the mid-1970s, Rev. Jones became a more prominent public figure. In 1975, Rev. Jones was named one of the most influential clergymen in the country. He actively campaigned for San Francisco mayoral candidate George Moscone; without the Temple voting bloc, Moscone would have likely lost the election.[108] “It was common knowledge that the church voted as a bloc.”[109] In 1976, he received the Los Angeles Herald’s Humanitarian of the Year award, as well as an appointment to the San Francisco Housing Authority. Lastly, Rev. Jones became active in Jimmy Carter’s presidential campaign; Peoples Temple provided a large supportive audience for Rosalynn Carter’s California visit.[110]

Tim Reiterman, prize winning journalist and Peoples Temple researcher, notes that “At a grass-roots level and in the chamber of bureaucracy, the Temple’s most effective public relations instruments were the people themselves.”[111] Despite the praise given to Rev. Jones publicly, the rank and file members in the community were the ones truly spreading the message. Temple members lived the social gospel; they were employed as social welfare workers, police dispatchers, probation officers, and other similar professions. Those employed in the private sector preferred to work as laborers at the lumber mill. They appeared to be hard workers, kind, generous, and genuinely interested in the welfare of others, particularly those in the lower classes.

“Meanwhile, Jones’ message was quietly evolving. The more he studied the Bible, the more he noticed the number of errors, contradictions, and inconsistencies it contained.”[112] Religious beliefs were being increasingly pushed aside and replaced by a revolutionary socialist message. Devotion to Rev. Jones was intended to replace devotion to capitalism and the Skygod. Calling out the righteousness of traditional religious beliefs during a meeting, Rev. Jones asked congregants, “If you don’t need a God, fine. But if you need God, I’m going to nose out that God. He’s a false God. I’ll put the right concept into your life…if you’re holding onto that Skygod, I’ll nose him out, then length every time.”[113] Years prior, Rev. Jones would not have dared to openly reject traditional Christian concepts. Now, with a large body of loyal followers and extensive public praise, he had nothing to lose.

Church meetings became very intense, yet most members were willing to comply. For the most part, Peoples Temple was an interracial, intergenerational, multiclass organization committed to changing the world. However, as the membership and political influences of Rev. Jones increased, Peoples Temple became “much more than just a church on Sunday …; it was a life commitment.”[114] Devotion became something to boast about, as well as something to use as a threat. As members threw themselves deeper into the inner-workings of the church, they would argue their devotion was more intense than others. Stanley Clayton remembers bragging about how little sleep he would get each night; they were made to feel guilty for taking luxuries such as sleeping or eating out at restaurants.[115] Eventually, members forgot to think for themselves and allowed Rev. Jones and prominent members of the leadership to think for them.

Former member Garry Lambrev recalls the time requirement that was expected of members, but also the energy felt during those meetings. “We had two meetings a day and Jim was the pulpit; the living, waking, acting pulpit.”[116] Rev. Jones’ enthusiastic and charismatic leadership style, even while requiring an inordinate amount of devotion from members, is extremely commonplace within new religious movements. “Charismatic leadership is pivotal in new religious movements to the extent that a movement emanates from a revelatory/mystical experience by the leader and the leader’s charismatic authority remains the primary internal power base.”[117] In order to maintain his authority, Rev. Jones had to continue to be appealing to his audience. The energy and expectations were high, but because he and his message were so powerful, members willingly obliged.

However, in stark contrast to the public image of a social gospel oriented, evangelical Pentecostal church, the internal dynamics began to change. Rev. Jones began to demand the loyalty from members, almost to the breaking point. Members who left rationalized their decision to reporters, stating that the “loving atmosphere gave way to cruelty and punishments.”[118] These claims and use of corporal punishment are not uncommon for new religious movements, however it is important to note that Peoples Temple is the exception, not the rule. Rev. Jones had begun to abuse a variety of drugs, increasing his paranoia and erratic behavior. His internal need to exert control and ascertain loyalty from members became an almost obsessive compulsion.

The alleged physical and verbal punishment inflicted upon Peoples Temple members is fairly typical of indoctrination techniques. Members were encouraged and often forced to attend catharsis sessions, wherein flaws or actions perceived to be against the church were brought up publicly. The accused individual would then be verbally degraded, even physically punished. “The verbal attacks became more virulent and menacing, until one day, Jones ordered the first members to be spanked with a belt. Once that line was crossed, beatings became de rigueur.”[119] These sessions, though questionable and obviously horrifying, were designed to force individuals into giving themselves over to the cause. “From inside the Temple, monitoring, catharsis sessions, and physical punishment seemed necessary to maintain standards of acceptable conduct and prevent internal dissension from taking hold.”[120]Additionally, public reprimands theoretically would reduce the likelihood of the individual acting out or speaking out again for fear of reprisal.

As a way of rationalizing the degrading behavior he seemingly forced upon unruly members, Rev. Jones argued that “the residual effects of the larger society needed to be ripped away like dead skin.”[121] Physical and verbal humiliation was a way to give oneself to socialism. To be treated like a subhuman was to understand the plight of those who are classified as subhuman, specifically the poor and African-Americans. “Among the techniques of control used by founders…are loyalty tests, expulsions, playing leading members off against one another, frequent shifts in policy…public humiliations and confessions, the use of violence against enemies both internal and external, and changes of physical location.”[122] Control and loyalty are two main factors a leader must maintain in order for a new religious movement to be successful. Rev. Jones needed to exert large amounts of control over his congregation in order to maintain his messianic role.

Another aspect that was strangely controlled was sexuality. Gathering extremely personal information had become commonplace; Rev. Jones utilized certain pieces of information to both exert control and profess his prophetic abilities. “Using all this ammunition, Jones created a sexually eclectic climate of intolerance disguised as tolerance, of guilt, repression and division.”[123] It is possible that the sexual atmosphere was a response to the counter-culture movement and sexual revolution occurring outside Temple walls. However, it is more likely that sex and sexuality was another method of control. By assigning himself as the only viable sexual object, as well as claiming to be the only true heterosexual, Rev. Jones ensured the focus of members would revolve around the cause and nothing else.