(Editor’s note: This article is republished courtesy of MLive.com. The original article appears here.)

(MLive.com editor’s note: This is the third installment of a five-part series on the life of Bay City native Shirlee A. Fields (nee Miller), who was among 918 people who died in a mass murder-suicide in Jonestown and other Guyana locations on Nov. 18, 1978.)

BAY CITY, MI — Moving from California and settling into Jonestown in the summer of 1977, Bay City native Shirlee A. Fields and her family found stability. Her husband, Donald J. Fields, continued working as a pharmacist, while Shirlee worked as a crop and herb garden manager, field hand, and nutritionist.

Fearing the persecution of Jews in America and yearning for a haven, the Jewish couple had joined Peoples Temple, the religious-social justice movement of the Rev. Jim Jones, around 1976. Joining them in their exodus to Jones’ supposed jungle utopia were their two children, Mark and Lori.

Stephan G. Jones, son of Peoples Founder the Rev. Jim Jones, told MLive he remembered the family.

“Shirlee seemed to have a good spirit about her,” he said. “Her children struck me as sweet, lovely kids. They enjoyed being part of the very diverse group of children that we had there. That doesn’t mean it was a happy place.”

On Nov. 18, 1978, Jim Jones led his followers in a mass murder-suicide that resulted in the deaths of more than 900 people.

Stephan Jones surmised Shirlee was the one who pushed the family to move to Jonestown, with her husband dutifully acquiescing.

“Don struck me as a really sweet guy,” he said, adding he tended to keep to himself and tried being of service any way he could and that Shirlee seemed more strident and involved.

“Don was a devoted husband, and I’m sure they shared values,” he continued. “It felt to me like both of them really did care about social justice and equality and integration. They were progressive in their thinking.”

Stephan Jones was scarce in the town itself, working long hours in the bush and unloading supply shipments from the Cudjoe, the community’s boat. He and others disillusioned with his father and Peoples Temple leadership were separating themselves from the adults in Jonestown as much as they could, he said.

They had a coded, derogatory word for the fervently loyal — “committed.” Neither Shirlee nor Don fell into this camp, he said.

In an April 1978 recording, Shirlee converses with Jim Jones directly, addressing him as “Dad,” as was usual for his followers. In her still-discernable Midwestern accent, Shirlee reports on the gardens’ yields and possible health benefits of local plants. Her tone is lighthearted, with her, Jones, and others laughing as they banter.

She tells Jones they found the plant gotu kola, an herb that could “preserve long life.”

“Burn it,” Jones quips.

“Yeah, right,” Shirlee chuckles as others applaud.

“No, I’m just teasing,” Jones resumes after a pause. “You know we need it. We gotta stay alive. We owe that to the revolution.”

Shirlee touts the herb’s memory-enhancing qualities. Addressing her by name, he tells her to let him know when she begins giving out the herb so there will be no more excuses of residents forgetting things.

In the same recording, he warns another woman for chastising Shirlee in front of others.

“Never criticize management in front of others,” Jones says. “You can say anything to me, privately, but you will not do it in front of (the) public. I’m making a point, g*****n it, and it better be heard. Shirlee Fields was in charge.”

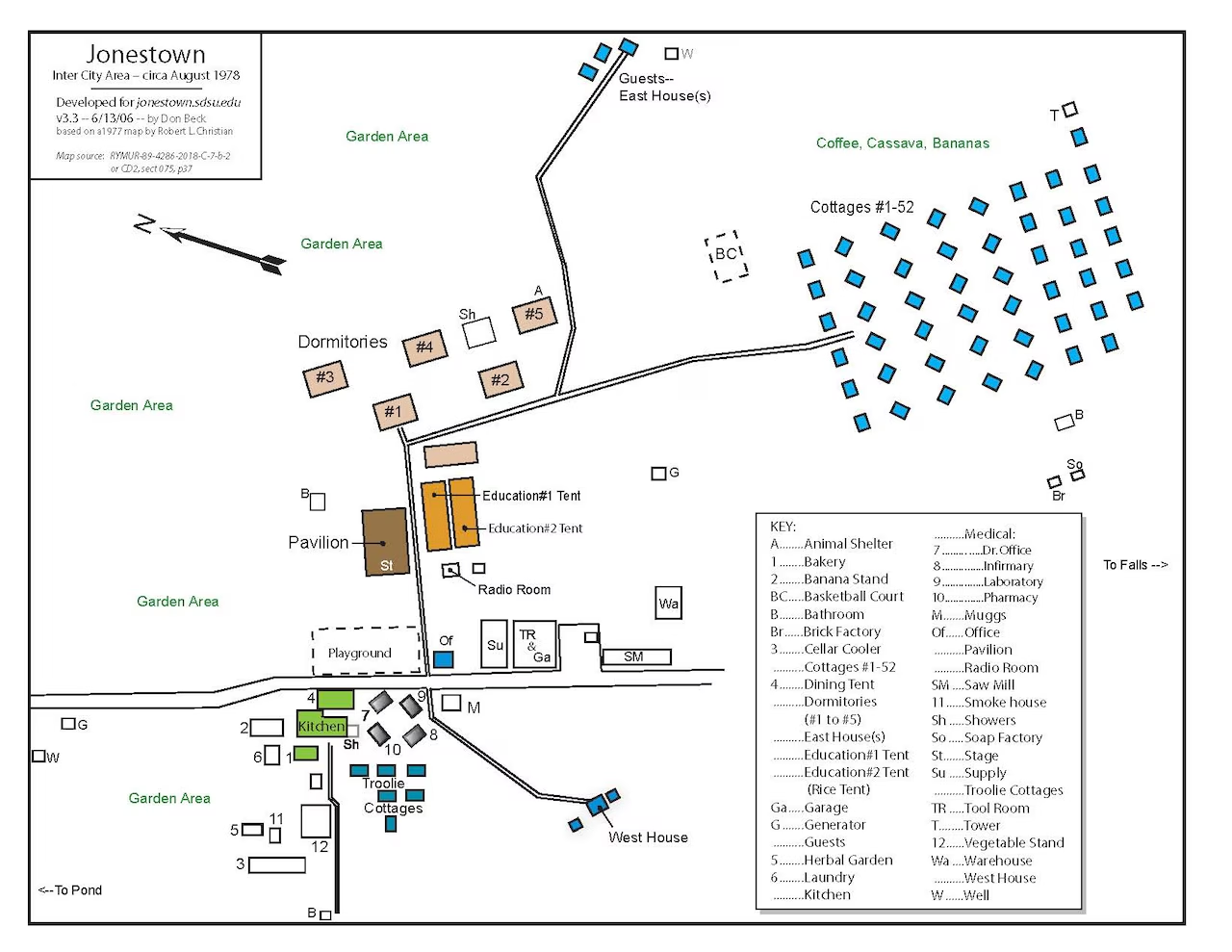

Jones separated nuclear families and wedded couples. Shirlee was in Dorm 2 in Jonestown, Donald in Cottage 52, Lori in Cottage 17, and Mark in Cottage 21.

Jonestown resident and former college professor Edith F. Roller kept extensive journals of her time there. In one excerpt, she notes Shirlee requested a separation from her husband, claiming he was trying to dominate her life.

“After some remarks on women’s liberation, her request was granted,” Roller wrote.

Roller also recorded Shirlee’s statements during a session of the group’s “Self-Criticisms,” wherein people would confess their “sins” for the community’s betterment.

“I have set myself up higher than those around me and acted like I was special but really I am much lower,” Shirlee said. “I have not cared about my children except in relation to myself. I have something inside that needs to come out – a feeling of love.”

Shirlee went on to say she had not treated her husband with respect and that she had assaulted him out of anger.

“Don told me about how he felt later,” she said. “He felt I was an animal out there.”

Shirlee’s final recorded words in this session are particularly prescient.

“A lot of our people have had to become animals to survive in the capitalistic world and I would be no different in the same circumstances. Now we are learning later how to ‘survive’ in the jungle.”

In May 1978, Donald Fields’ mother contacted the U.S. State Department concerning the welfare of her son and his family. She told federal agents she believed her son was being held in Jonestown against his will and that she knew of 25 to 30 other citizens concerned about their relatives being held in Guyana.

The State Department forwarded the request to the U.S. embassy in Guyana’s capital of Georgetown, stating it would appreciate someone checking on the Fieldses. A U.S. consul on Nov. 7 visited Jonestown and spoke with Don Fields, who asked his mother be assured he was “well and happy.”

In other recordings, Jones praises Don Fields for doing “exceptional work” in the pharmacy.

Jones and his upper echelon also tasked church members with writing what they would do if there were a final White Night, their term for crisis drills that, according to The Jonestown Institute, often ended in scenarios of mass death.

“I would like to help eradicate [sic] hunger throughout the world and preserve a communistic life for children, and that is what I would fight for,” Shirlee wrote. “If I were to die tomorrow I would have no regrets.”

Her husband stated he would like to work in healthcare and in other countries but would “fight for what we know is right, especially for all the children here and in the world.”

Daughter Lori, age 12, gave a more disturbing response.

“I would have someone drop me in the middle of Calif., in airplane in the night,” she wrote. “I would write notes to [former members]. The note would say to meet me in a certain place at a certain time. I could set a bomb to the place and blow them up and me too. I could disquise [sic] myself as a denist [sic] then I could drill in one of the traders [sic] teeth and put a beeper device.”

In another document from Jonestown, Shirlee asserts her allegiance to Jones.

“Dad’s high points are high commitment – his dedication; how he works day and night – he lives at the level of the people – equality – no one is any more special than another – dedication to ideals – dependable to the people,” Shirlee wrote.

“I believe Dad stands for those who cannot and he believes in individual and group criticism. Dad is willing to hear and believes in free thinking as long as he hears it first. Dad is the principle and he stands above all else. He never raises his voice, dependable; not deviant such as molesting children.”

Her daughter wrote a similar testimonial.

“Dad does not believe in God, he believes he is the only god,” she wrote. “He will die for us.”

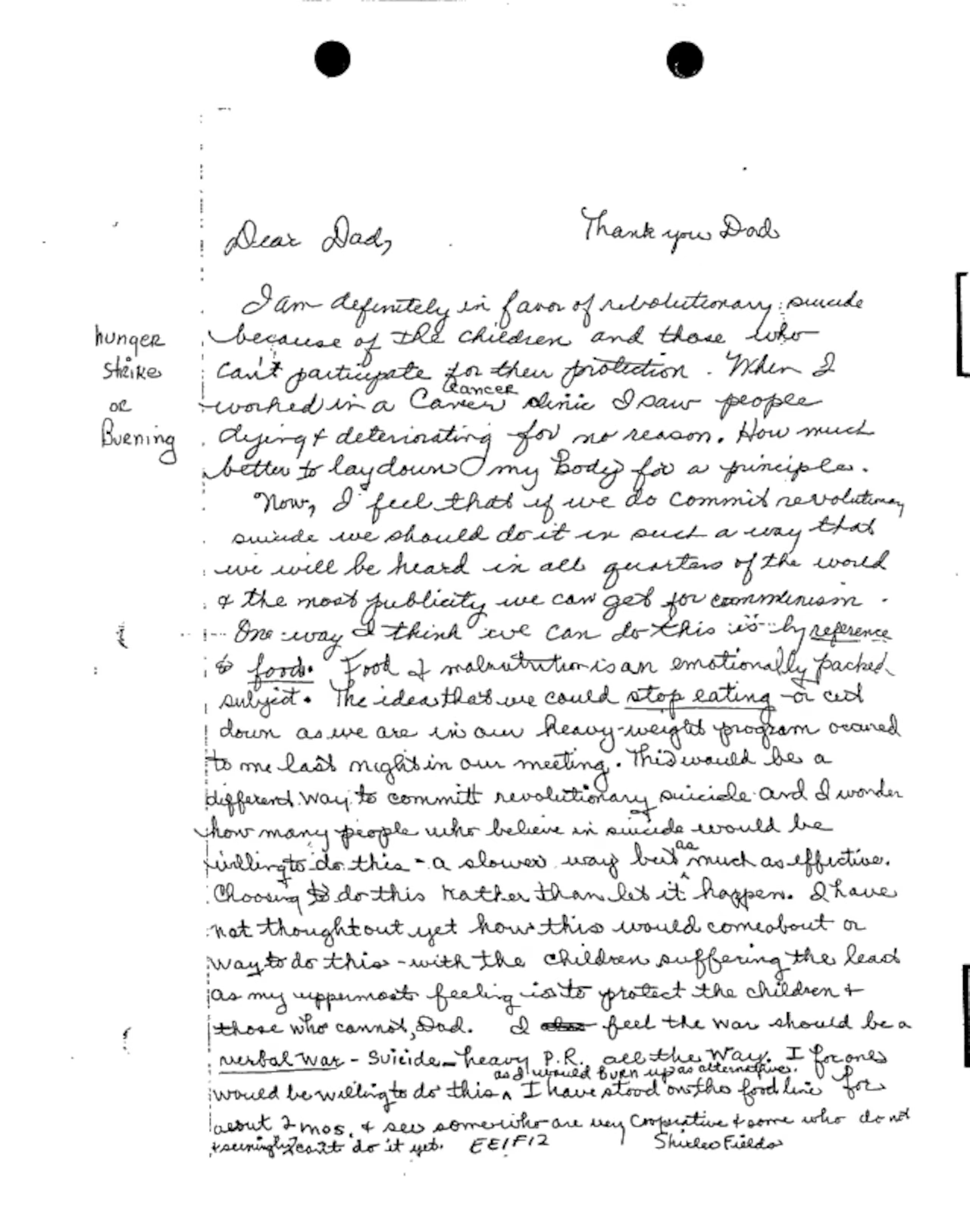

With the idea of mass suicide hovering, some Temple members contributed ideas on how to best enact it. Shirlee was among them, proposing starvation or self-immolation in a letter she penned to Jones.

This note was unknown until Fielding M. “Mac” McGehee III, a researcher and a leading authority on Jonestown, and his wife Rebecca Moore, found it when they obtained documents from the FBI in 2009.

“When I find something like (Shiree’s note), it’s been there all the time, hiding in plain sight,” McGehee said. “But no one has seen it.”

The undated letter in its entirety reads:

“Dear Dad, Thank you Dad. I am definitely in favor of revolutionary suicide because of the children and those who can’t participate for their protection. When I worked in a cancer clinic I saw people dying & deteriorating for no reason. How much better to lay down my body for a principle.

“Now, I feel that if we do commit revolutionary suicide we should do it in such a way that we will be heard in all quarters of the world & the most publicity we can get for communism. One way I think we can do this is by reference to food. Food & malnutrition is an emotionally packed subject. The idea that we could stop eating or cut down as we are in our heavy-weight program occurred to me last night in our meeting. This would be a different way to commit revolutionary suicide and I wonder how many people who believe in suicide would be willing to do this—a slower way but as much as effective. Choosing to do this rather than let it happen. I have not thought out yet how this would come about or way to do this—with the children suffering the least as my uppermost feeling is to protect the children and those who cannot, Dad.

“I feel the war should be a verbal war — suicide — heavy P.R. all the way. I for one would be willing to do this and I would burn as an alternative. I have stood on the food line for about 2 mos. & see some who are very cooperative & some who do not & seemingly can’t do it yet.”

(Cole Waterman is a Michigan-based crime reporter with a long-held interest in Peoples Temple and Jonestown who has submitted numerous primary source transcripts from the FBI’s FOIA files to the site beginning in the fall of 2023. He can be reached at Cole_Waterman@mlive.com.)