(E. Black is an independent researcher with an interest in Peoples Temple as a new religious movement and social phenomenon. Her particular focus is exploring the relationship between Peoples Temple and an earlier new religious movement, the Peace Mission Movement of Father Divine. Her other article in this edition of the jonestown report is Wives of God, Mothers of the Faithful: Edna Rose Baker and Marceline Jones as Mothers Divine. Her previous articles are here.)

“[Father Divine] was preparing… a ‘Vanishing City’… [from] which… people would leave this world. They would be the purest of the pure in heart.”[1]

“Father Divine… announced to the press that it was his intention to found a Divine City… situated far from the negative vibrations of… the worldly.”[2]

“Don’t you want to go? For this cause came I into the Flesh and all will be fulfilled.”[3]

Peace Mission terminus point: Woodmont

In 2013, it would seem that the greatest difference between the Peace Mission and the Peoples Temple couldn’t be more stark, obvious and simple: The Peace Mission, however diminished or obscure, is here and the Peoples Temple isn’t.

The Peace Mission arose from the ministry of a short, squat African American itinerant preacher, who called himself “the messenger” and “God” almost a century ago. The movement is still alive and functioning today, if only barely so. After experiencing a burst of publicity and activity, as well as a ballooning and international membership some 80 years previous, the rapidly-aging and remaining core of the Peace Mission is steadily shrinking back into the single house/church commune modality that it had evolved from and yet had never actually transcended.[4]

The Peace Mission house/church commune center is known to the world as the Woodmont Castle. The mansion sits atop a high hill on a 72-acre estate; the acreage includes outbuildings, greenhouses, horse stables, a swimming pool, tennis courts, a stream and tree-lined walking paths.[5] All of these amenities were part of the property when it came into the hands of the Peace Mission movement. Since then the movement has itself added some noteworthy features of its own.

Forty-five years ago – and three years after Father Divine’s death – the ornate coffin that contained his tiny body was placed in the bottom of an august vault inside of a hexagonal- and pyramid-topped mausoleum built specifically for this purpose. The Peace Mission calls it the “Shrine to Life.” A second addition, a building that is nearing its completion, is the Father Divine Library, being constructed to house Peace Mission memorabilia, books, papers and artifacts accumulated over its history. Its proprietor is the leader of the Peace Mission and the widow of Father Divine, Mrs. Sweet Angel Divine, better known as Mother Divine.[6]

The 90-year-old Mother Divine has already outlived her husband, who died at the age of 85. When she joined the headquarters secretarial staff of the Peace Mission in 1946 at the end of World War II, she was either a 17-, 18-, or 21-year-old member of the “rose buds,” the female youth auxiliary of the Peace Mission.[7] In a normal church, the next tier of leadership would be groomed to accept the responsibilities of taking over and keeping the organization afloat. But the Peace Mission by its own admission is not an “orthodox church” nor is it the “established church.”[8] It is instead a radical and totalist group, dedicated to realizing the whims and pronouncements of Father Divine, its long-deceased founder. Members are encouraged to “let go” and “let God” – Father Divine – rule their thoughts actions and impulses. One of the impulses that Father has ordered forbidden is the sexual reproduction of his unperfected followers, nor are they to recruit members. As a result, unless an individual somewhere has an epiphany proclaiming that “Father Divine is God” and decides to join the movement, it is biologically destined to end.[9]

With no new members to replace the ones who leave or die, the Peace Mission is in a conundrum of its own making. Yet this “no growth” or “negative growth” policy is not the result of some happenstance. It was set methodically and with calculated foresight almost 100 years ago, from its earliest days as a tiny, obscure Baltimore, Maryland cult and codified in print through the Peace Mission’s own press more than 80 years ago.[10]

Father Divine sought to wipe the “evil” of physical propagation off the face of the earth. The Peace Mission teaching states that “all humanity” born by acts of sexual intercourse are born “wrong.” It also teaches that when “men learn not to be born, they will also learn how not to die.”[11] Thus, the Peace Mission order is “No sex” and “No undo mixing of the sexes.”

This means that, even though the Peace Mission is still physically here and will continue to be – as long as a dwindling group of celibate individuals live cooperatively by observing and obeying Father’s teachings – it is designed from top down to slowly atrophy and to eventually and totally disappear, leaving only the memory of its “sample and example” of lived and realized universal brotherhood as an eternal guide post to the principle it established.

Father Divine: God Has Come

“Because your God would not feed the people, I came and I am feeding them… That’s why I came, because I did not believe in your God.” –Father Divine[12]

Father Divine ministry’s has been described as “perplexing,” and he himself as a “mind controlling cult leader.” Yet he established himself in history with his pioneering record on equal rights for all Americans regardless of color or creed, as well as by building a business empire around a form of cooperative socialism that provided food, clothing and shelter to many during the Great Depression of the 1930s.[13]

His many followers called him “God, in a body” and testified that he could and did heal bodies, uplift spirits and raise the dead. Living believers declare that, by believing on him, they will never die. He positioned his ministry and presence as a triumph of principle and declared to the world that, “with or without a body,” he would triumph.[14]

Nevertheless, Father Divine’s other edicts – such as the “no sex” and “no reproduction” order – and his rather callous way of dealing with the prepubescent children who were deposited into his communes when their parents joined the Peace Mission, has deeply troubled many. While mental health experts fretted about the effects and impact of the Peace Mission’s views on children and child-rearing, Black Nationalist critics of his ministry openly accused Divine of being under the control of scheming whites who, through the no-sex policy, will lead his predominantly Black female followers to commit “race suicide.”[15]

New York, New York

The Peace Mission movement was proclaimed in 1932 during a time of great national economic hardship. Its home of New York City was not only the USA largest metropolitan area but also its financial capital. Father Divine’s headquarters at 20 West 115th Street was in the Harlem neighborhood that was rapidly becoming the place with the largest Black population outside of the American South. Divine became one of the largest landlords in Harlem, and the mass meetings and Holy Communion meals that he held in the Rockland Palace, a converted boxing space, made headline news.[16]

He also became a player on the political activist scene. Two mayors of New York City – John O’Brien and F. H. La Guardia – both campaigned in front of the Peace Mission soliciting support. The Peace Mission also sponsored and carried out massive voter registration campaigns and encouraged its members, many of whom were illiterate and from the rural South, to become educated enough to be able to read the political literature and to vote.[17]

Father Divine saw himself as the world’s only savior standing on principles and not personality. He targeted Harlem’s large Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) and African Communities League contingent, founded by Black Nationalist pioneer Marcus Garvey, for co-option and absorption. His attempts met with some success, and several former Garveyite leaders, including its former assistant international organizer and former editor of the Garvey movement press – as well as rank and file members – switched over to the Peace Mission.[18]

Another group that the Peace Mission courted during this period was the Communist Party USA, participating in its political meetings and contributing three- to six-thousand people to its huge May Day marches through the streets of Harlem.

The Peace Mission press embraced the ideas of CPUSA, stating “The Communists are the only outstanding organization or party… to stand for… social equality… Regardless of race, creed, or color… every true American and Christian should unite himself with these principles…even it brings upon himself the label of ‘Communist.’” Father Divine declared that he was pleased to be “participating with [his] Comrades, the Communists” but before his own audience, he described his work as “what the Communist have been trying to get you to see and do and be, I have accomplished.”[19]

In fact, it wasn’t purely cooperating with other groups that made the Peace Mission a political force. Divine had his organization convene a political convention of its own. With 5,000 delegates, the International Righteous Government Convention passed the Righteous Government Platform which – among other things – called for the death penalty for lynching, the abolition of war and government reform. It opposed corporate exploitation and called for the nationalization of the banks. It also passed a resolution calling Father Divine, God.

In his quest to make a no-sex, interracial utopia of gender-segregated righteousness on earth into an immediate reality, Father Divine used the collective purchasing power of his followers to buy land and buildings in mostly wealthy and white rural Ulster County, New York. He called this rural project the Promised Land, declaring his intention to build a Divine City on the site, far away from the bad vibrations and wicked temptations that his largely Black inner city urban followers were constantly subjected to. Every week, Peace Mission members packed onto buses to ride from Harlem to rural upstate New York and back again. But before he could consolidate all the moving parts to bring his ultimate intent into being, however, internal dissent, criticism from the outside and the consequent negative press diverted his attention.[20]

Apostates say “God? No. He’s just a natural Man!”

In the mid-1930s several high publicized scandals rocked the Peace Mission as it was reaching its membership and organizational apogee. Because of its radical stance on race and gender, and its leftist political posture on most issues of the day, the Peace Mission became the focus of the enmity not only of such terrorist groups as the Ku Klux Klan, but also of some mainstream political personages and press moguls.

If that was not enough, the Peace Mission’s carefully-crafted messages of the movement’s commitment to sanctity, propriety and celibacy – always questioned and doubted by its critics and much of the public – took major hits in 1937. John Hunt, a high-level scion from an ultra wealthy White family that had joined the Peace Mission in the early 1930s, became embroiled in an internal movement sex scandal that threatened to reveal details of some of the Peace Mission’s very unorthodox sexual escapades. Ironically, Hunt, who was on Father Divine’s top level staff, serving as the Peace Mission representative-at-large to the West Coast, was known within the movement as John the Revelator.

During one of his tours of the far flung Peace Mission extensions outside of its New York/New Jersey metropolitan core, Hunt had traveled with the underage daughter of a Denver area Peace Mission couple, Norman Lee and Elizabeth Jewett. This occurrence was in and of itself not unusual, as the leaders of the movement were notoriously unsupervised in their comings and going. What was unusual was the fact that the subsequent details of what had happened between the 30ish Mr. Hunt and his personal secretary and new traveling companion, the teenage Divinite, Martha Dove, became public.

The Jewetts, a Caucasian family, were rank-and-file Peace Mission members or children. Mr. Jewett, a government agricultural employee, had converted to the Peace Mission after Father Divine allegedly healed him from a painful and incurable dental condition. While he was, by all accounts, a devoted Divinite, his wife may have been less so. It was her increasingly insistent prodding about the whereabouts of their teenaged daughter named Delight that finally galvanized him to begin inquiring about the possible whereabouts of his daughter.

The deflections and ambiguation that he received in response only increased his wife’s growing concern. With a growing sense of alarm, the Jewetts traveled to Peace Mission headquarters in New York to further investigate their daughter’s disappearance. Again, they were given the runaround.

The Jewetts persisted in demanding to know what had happened to their daughter, and after a delay, they were invited to the movement’s rural Promised Land. There – as per the Peace Mission protocol – they were separated by gender. In the men’s quarters, Mr. Jewett talked with Mr. Hunt, and soon afterwards was ushered into the presence of Father Divine himself.

The Peace Mission leader assured Mr. Jewett that his young daughter was safe, healthy, and happily living in an all-female Promised Land extension. With the question of his daughter’s whereabouts apparently resolved, Father Divine and his staff escorted Mr. Jewett around the prospering Promised Land enterprises, and the movement leader even offered him a job as a manager of one of its expanding properties. Mr. Jewett was ecstatic.

But when he shared the good news of the job offer with his wife, she was less so. Although taken to the female Peace Mission quarters and extended all pleasantries and even a promised audience with Father, Mrs. Jewett swept aside all pleasantries and began searching for her daughter. But when she did find her, the reunion was not a happy one. Despite not having seen or spoken to each other in months, young Delight unsmilingly told her mother not to touch her as she didn’t want her mother’s mortality to rub off on her. She was now a Holy Virgin, the daughter said, and destined to become “the mother of the world’s savior.”

Elizabeth Jewett told her husband about the encounter after the communal dinner that night, but Lee Jewett listened impassively. His faith in Father was still strong. As alarmed by her husband’s dismissive response and unbroken devotion to Father and the cause as she was by her daughter’s alienation, Elizabeth Jewett’s faith in Father had evaporated, and her disillusionment was complete. Now that she knew the depths of duplicity that was the Peace Mission, Mrs. Jewett changed tack.

Since the movement was going to hire him anyway, Mrs. Jewett told her husband, he should demand some financial compensation from Mr. Hunt for the ordeal that he had subjected their family to. Mr. Jewett agreed, but the Peace Mission would have none of it. When the movement’s lawyers told the couple that under the circumstances no payment would be coming, Mrs. Jewett then demanded that they let them leave with their daughter in tow. Whatever agreement they may have made to keep the entire matter private, it ended the moment that the Jewetts arrived safely home to Denver, and soon the entire story was national news.

The negative publicity from the Jewett affair started an avalanche of crises for Father Divine and his movement. Under the cover of national press exposure, two more female ex-Divinites came forward and proclaimed that Father Divine had pressured them to perform sexual acts with high-level male inner circle officials. The FBI began a multiple state search for Mr. Hunt and the others implicated in the affair.

Father Divine publicly distanced himself and his movement from the Hunt fiasco – denouncing his aide’s alleged seductions and proclaiming him no longer a follower of his – but privately the Peace Mission hid everyone involved or implicated, providing them with escape into the labyrinth of Promised Land properties and businesses, thus keeping them one step ahead of the pursuing authorities.

John Hunt finally surrendered, as did his charged accomplices. During his trial, his accuser Delight took the stand to tell of her seduction and rape under the cover of the authority of Father Divine’s teachings. Hunt admitted to the charges but was adamant in exonerating Father Divine of any of his actions. Convicted of the charges and sentenced to prison, John Hunt vowed to continue Peace Mission missionary work among the inmate population. His accomplices were acquitted and silently reabsorbed back into the Peace Mission and reassigned other duties. For his part, Father Divine wrote an open letter to his wayward disciple which, while upholding the judgment against him, extended his forgiveness.[21]

Yet all was not well in the kingdom of Father Divine. When court process servers went to a mass meeting to serve Father a subpoena, the leader instructed the crowd to “get ‘em.” The enraged crowd of Divine followers set upon the servers, beating, kicking and scratching them before throwing them out of the meeting hall. One of them ended up prone on the sidewalk, bleeding profusely from a stab wound from an ice pick.[22] Meanwhile, Father Divine had disappeared in the melee, and when he didn’t respond to an ensuing arrest warrant, law enforcement officials launched another multi-state search and another invasion of Peace Mission properties, including the Promised Land.

Although the Peace Mission was at its apex, the public revelations about its sordid sexual underpinnings led credence to the suspicion that the movement was a Black-led White sex slavery cult which lured people in, took all their money, and brainwashed its gullible followers. The scandal took their toll. The aged Peninnah Divine, Father Divine’s official wife and the Mother of the movement’s faithful, suffered a collapse and had to be hospitalized. For a movement that claimed miraculous faith healings and even immortality for the most devout among them as a distinguishing signature of distinction, this was quite a potentially devastating blow. The embarrassment only grew when the press revealed that a very few in the Peace Mission even bothered to acknowledge their female paramount leader in her hour of health affliction, let alone visit her in the hospital.[23]

As Father Divine worked to put out the various fires that were springing up all over his kingdom, his top female aide, a Black woman whose movement name was Faithful Mary publicly defected. Realizing that she might have to take the fall for Father’s aiding and abetting John Hunt evasion of the law, and witnessing the FBI and police invasions of the various Peace Mission properties, she decided it was best to come clean. And so she did, in an exposé entitled God: He’s Just a Natural Man.[24]

Faithful Mary revealed a Machiavellian character within Father Divine which many had suspected but which the faithful had fervently denied. Although Father Divine had allowed her an almost exclusive privilege of holding most of the Promised Land and other movement properties in her name, she said that the two of them had increasingly bickered over funds. She also claimed that he had set up the entire Peace Mission apparatus as a racket to skim money from the membership and its businesses to sustain his affluent lifestyle. As proof of her charge, she admitted that Divine often designated her as his collection agent.

Ashamed of her own duplicity, Faithful Mary confessed to being the sexual partner of the allegedly celibate Father Divine and claimed that Father Divine was not exclusive sexually with her either. He regularly seduced other, young female disciples, getting them to come to his quarters late at night, individually or in small groups. When they were either partially or fully naked, he would masturbate them to orgasm, all while telling them that they were not sinning but giving themselves to God. Faithful Mary also claimed that lesbianism was rampant in the sex-segregated Divine communes.

All this happened, Faithful Mary continued, while she served as the top aide to his wife, Mother Penny Divine, whom, Mary said, she really and truly respected. Mary added that she had been disgusted by the way the elderly and increasingly infirm Mother of the Movement was treated in private beyond the unsuspecting eyes of most of the members.

Shocked by these sordid revelations, member after disgruntled member of the Peace Mission began to withdraw, some quietly and some not. Among the latter was the married couple Thomas and Veranda Brown, known as Onward Universe and Rebecca Grace while in the movement. It was their desire to reconnect and live together again as husband and wife, after living the previous six years with God “angelically” and a part for the cause, that caused them to withdraw from the movement in 1934. They also asked for a return of the money that they had turned over to the movement when they first went communal, but Father refused.

In 1937, with the revelations about the Peace Mission in the press and the defection of Faithful Mary providing a safe context, the Browns decided to take Father Divine to court. They eventually won the court battle, but lost the war. Father Divine not only refused to pay up, but rather than leave himself in the court’s jurisdiction, he chose to uproot his entire Peace Mission, including his headquarters and press and as many of his followers that would come with him, from New York State and into Pennsylvania.[25]

Retreat to Pennsylvania: God Curses New York

“I may turn the United States upside down! … It is absolutely immaterial.”[26]

The move to Philadelphia cost the Peace Mission much more, both immediately and in the long term, than simply paying the court judgment would or ever could. With that single action, Father Divine has removed his principal structure from its natural base in Harlem, where his movement had gained prestige and political patronage over the years. He also left his ailing wife to die alone in seclusion in the Promised Land. Finally, he abandoned any hope of ever turning his properties there into a Divine City.[27]

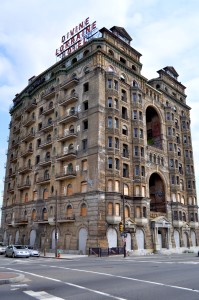

Shortly after arriving in Philadelphia, Father Divine purchased two properties that would eventually symbolize the Peace Mission: the Divine Tracy and the Divine Lorraine Hotels. The move also resulted in another fundamental shift in his ministerial career and the character of his movement. The Peace Mission founded formal churches, drawing up strict guidelines and by-laws for gender-based auxiliaries to operate in them. His restrictions against sex, once only demanded among his co-workers and those living in his apartments or hotels, was now dictated as an edict for all of his true followers. With these changes, the spontaneous character of the Peace Mission – with its free mass meals and services to the public – was now gone forever, as the movement turned inward and politically conservative. In retrospect, the 1942 move to Pennsylvania marks the end of the Peace Mission’s years of growth and expansion, and heralds its long, slow road to eventual organizational and membership extinction.[28]

Father Divine could have evaded these consequences. He could have paid the fine – even under protest – then continued his operations in New York, including his plans to turn the Promised Land into the earthly utopia of his mind. But it was not to be. For Father Divine, nothing was more important than principle and the cause as he understood and presented them. As for the city and state from which he fled, and the properties, people and the Promised Land he had previously touted, he huffed that they needed him far more than he needed them. The entirety of New York could go down “like Sodom and Gomorrah did” and “it [would] be immaterial to” him.[29]

Woodmont: God lays down his body to save the world

Eleven years after the Peace Mission’s move to Philadelphia, Werner Hunt, a brother of apostate John Hunt, presented Father Divine with a gift.[30] Over the years, the Hunt family, with its prodigious private wealth, had almost single-handedly bankrolled the Peace Mission movement, buying mansions, expensive cars and state-of-the-art equipment, as well as running the movement’s internal press. Despite John Hunt’s high-level defection from the movement, the remaining faithful members of the Hunt family continued to have Father Divine’s utmost confidence as they continued to joyfully pay his bills.[31] But nothing so far matched the gift bestowed upon Father by Werner Hunt, known in the movement as “John Devout.”

Woodmont, a 78-acre estate capped by a mansion which more resembled a palace, became Father Divine’s property after John Devout purchased it and turned it over to his leader. From this many-roomed parsonage Divine, and his young new white wife Sweet Angel Divine lived the life of landed gentry, making pronouncements – all meticulously recorded by secretaries for later print – on the happenings of the day. Father Divine and the new Mother Divine also traveled in style, periodically driving his Duesenberg into town to receive the adoring cheers and well wishes from the crowds at the various Peace Mission hotels and inner city establishments that comprised their realm. It was in this atmosphere of luxury that Divine began to slow down and increasingly showed sign of his advanced age.[32]

Woodmont, a 78-acre estate capped by a mansion which more resembled a palace, became Father Divine’s property after John Devout purchased it and turned it over to his leader. From this many-roomed parsonage Divine, and his young new white wife Sweet Angel Divine lived the life of landed gentry, making pronouncements – all meticulously recorded by secretaries for later print – on the happenings of the day. Father Divine and the new Mother Divine also traveled in style, periodically driving his Duesenberg into town to receive the adoring cheers and well wishes from the crowds at the various Peace Mission hotels and inner city establishments that comprised their realm. It was in this atmosphere of luxury that Divine began to slow down and increasingly showed sign of his advanced age.[32]

Members of the movement found themselves in crisis. As Sarah Harris points out in Father Divine: Holy Husband, her contemporary account of the Peace Mission, its followers were so symbiotically attached mentally and emotionally to the person of Father Divine, that they would suffer an existential crisis when the elderly cult leader died. “If Father Divine were to die, mass suicides among the Negroes in his movement could certainly result.”[33]

In 1960, Father Divine was admitted into a hospital after going into a diabetic coma. He recovered, but was visibly diminished. Three years later, he stopped appearing in public altogether, and on September 10, 1965, Father died in his Woodmont castle, ending a 50 year-career in which he intimated – and many believed – that he was God almighty, in the flesh and could never die.[34]

Although Harris’ predicted mass suicides among his followers didn’t occur, she had still been prescient: the Peace Mission movement, as strictly lived per Divine’s orders and dictates, was itself a mass suicide movement, only doing so in slow motion and over time.

What was misunderstood at the time, then – but is seen more clearly in hindsight – is the Peace Mission’s fanatical program of living self-negation for the cause is one that is a form of slow and incremental mass suicide for the committed membership. Moreover, this outcome – created by a singularly consistent fanatic master mind and maintained and sustained by the strict adherence to his will and teachings by his obedient followers – was intentional. It is an outcome Father Divine’s elderly and rapidly-dwindling number of remaining devotees, even in his physical absence, are still committed fully to fulfill and carry out.[35]

Peoples Temple terminus point: Jonestown

Peoples Temple, once so full of life, laughter and light is no more. It horrifyingly imploded on the evening of November 18, 1978. Rev. Jim Jones, the leader of Peoples Temple and the mastermind of its ultimate collective demise and his wife, Marceline, were among the sprawled bodies as they joined his rank and file followers in a final and bizarre act of solidarity and equality.[36]

In the years following the tragedy, focus was squarely on the immediate event, and rightfully so. For the first time in U.S. history, a sitting congressman had been murdered in the line of duty, as he attended to the concerns of his constituents. More than 300 minors under 18 – including 13 infants under age 1 – had also been murdered, their bodies among the 909 at Jonestown. How could this have happened? And what could be done to prevent it from ever happening again?

In trying to address and answer these concerns, what went largely unnoticed was the fact that Jim Jones had largely and consciously built his Peoples Temple on the legacy – and in the image – of the earlier Peace Mission movement of Father Divine and its attempt to build and realize an earthly interracial utopia.[37]

Jim Jones: Same God, Second Body[38]

“I am creator of …the Peace Mission, I am the creator of that.”

“There wasn’t any God till I came along. There was nobody to help the people. Your God of religions and Bibles– the babies are going to bed hungry, black people have been treated like dogs just because of the color of their skin, Jews were murdered, and they were supposed to be the chosen people of the so-called Skygod, there was no Skygod, and I’m an earth God, though, child, and I’m very much alive.”[39]

Within two years of his founding Peoples Temple, Jim Jones, a youthful white Christian church minister, was in deep discussion with the ailing and aging Black leader of the Peace Mission, both in face-to-face meetings as well as by letter and telephone. These were not idle chats. These conversations between the two very different men – from different backgrounds and eras[40] – focused on the cause and the principle of the embodied God or universal mind. Both men believed they had been chosen to express and manifest this principle on the material plane in the fight to establish total social equality and social justice for all. For the two men, life and death were both secondary, expendable to the cause and principle.

Both men proved that they took there respective charges quite seriously. Jim Jones was of the thought that as Father Divine’s body steadily declined, Jones himself was transferred more and more of his mind and power. Ultimately Jones sought to be the same mind and God that Father Divine, in his prime, had been.[41]

San Francisco

The 1970s Bay Area Peoples Temple experience was the equivalent to the headiest years of the Peace Mission during 1930s Harlem, New York. Although based earlier in the rural Northern California community of Redwood Valley, the core of the Temple membership and most of its impact was in the city of San Francisco. It was in this city that the imposing former Albert Pike Memorial Scottish Rite building located in San Francisco’s Fillmore neighborhood became as iconic and symbolic of Peoples Temple as the Divine Lorraine or the Divine Tracy Hotels had been for the Peace Mission in Philadelphia.[42]

Jim Jones quickly became a player on the political activist scene, and the volunteers which his Temple provided to mayoral candidate George Moscone has sometimes been credited with putting him over the top in a close race. But Moscone was not the only one. Jones organized his followers to phone bank, walk precincts and vote for the candidates and causes that he endorsed.

In 1976, Jones was appointed to the powerful San Francisco Housing Authority Commission and shortly there after became its chairman. He spoke at the 1976 grand opening of the San Francisco Democratic Party Headquarters along with Rosalynn Carter, whose husband Jimmy Carter would be elected president later that year. With Peoples Temple members packing the audience, Jones garnered even louder applause than Mrs. Carter did from the crowd when he spoke.

Not content with courting only mainstream politicians, Father Jones cultivated the radicals as well, just as Father Divine had done with the Radical Utopians, Garvey’s radical Black UNIA and the Communist Party USA in the 1930s. The Temple supported such leftist and radical notables as Angela Davis, a Black university professor and member of CPUSA, and First Nation activist Dennis Banks and his wife Ka-mook.

But it was the more mainstream politicians who attended Peoples Temple services that gave the increasingly-activist movement its credibility. The members of the Bay Area political elite with whom Jones rubbed shoulders were San Francisco Supervisor Harvey Milk, District Attorney Joseph Freitas, State Assemblyman Willie Brown, State Senator Milton Marks, Lieutenant Governor Mervyn Dymally, and California Governor Jerry Brown.[43]

But despite – or because of – this, Father Jones came under increasing scrutiny by investigative journalists, who eventually interviewed defectors and apostates to learn the unsavory aspects of Peoples Temple, a different narrative on the Temple than the one its founder presented. Soon, with the threat of further negative investigations both inside and outside of his fold, and the negative press surrounding it, the Temple sped up its plans for its upcoming mass migration of members from California to Guyana.[44]

Apostates

Peoples Temple has been deeply criticized, both before and after the events of November 1978, for how it dealt with the issues of internal dissent and apostates, and understandably so. Yet given the context of what Peoples Temple was and what it sought to do in light of its connection to the Peace Mission, what seems at first glance just simply incomprehensible – the catharsis meetings for leaders and members; the harsh, internal disciplinary measures; and the internal monitoring and control, particularly of members who lived communally – becomes less so.

In a serious attempt to show the larger world a consistent vision of a utopian community, free of racism, sexism and class division and one of cooperation, unity and love, Temple leaders were motivated to prevent and squelch dissent within its membership before it became public. In that way, it was like the Peace Mission: Peoples Temple could not afford, nor would it tolerate a spot or a wrinkle of discordance on its public face. Everything was subordinate to the cause, including the leader, and indeed the leader was successful insofar as his followers were convinced that he had died to self and personally embodied the cause.[45]

The ex-members who had become infected with the virus of doubt that led to the disease of disillusionment were seen as enemies to the cause. Mirroring the rise of the Temple’s influence, the entire apparatus of surveillance and coercion within the group was designed to prevent the ascendancy of such threats.[46]

It is that desire to save face and preserve the integrity and dignity of the cause that led to such strong and seemingly exaggerated reactions to the departures of its most well-known defectors, including the Eight Revolutionaries (defected in 1973), Al and Jeannie Mills (defected in 1974). Bob Houston and Joyce Shaw (defected in 1976) Grace and Timothy Stoen (defected in 1976 and 1977 respectively).[47] It also sets the context for the migration and the tragedy that came as a result of and a reaction to these apostasies.

Guyana: “Situated far from the negative vibrations of…the worldly”

When the Eight Revolutionaries defected from Peoples Temple in 1973 claiming that internal contradictions had arisen that threatened to make a good movement go bad, the response of Temple leadership was two-fold: first Jim Jones introduced the concept of group suicide for the cause during meetings with his leadership.[48] Secondly, he instructed some of his lieutenants to procure land in a foreign country on which to establish an international missionary outpost that would serve as a possible retreat for his community.[49] The two can be seen as an either/or contingency, not necessarily as two sequential steps, although the latter might have been in Jones’ mind from that point.

Migration to another place in which to bring forth the Divine city was always a part of the Peoples Temple possibilities, as it had been with its earlier template, the Peace Mission. Whereas Father Divine looked to rural communities of New York and the New England states for his Utopian City, Jones considered other countries. Cuba, Guyana and Brazil were early candidates for him, but he also looked at the Caribbean island nation of Grenada which he had visited in the early 1960s. Later, once the move to Guyana was complete, he contemplated the Soviet Union as well as the African nations of the Congo and Zimbabwe.[50]

It should be noted the Peace Mission, an international movement since the 1930s, had a long-established branch in Guyana before, during and after the Temple’s years there. The country was attractive to both movements for the same reason: it was English speaking, and its population was largely Black.

Jonestown: The Divine City That left “This World”

[R]ather than be misunderstood… I would slit my throat and let all (the) blood run out… all that I have sacrificed… if it is not accepted, I will go away.”[51]

“I saved them…but the world was not ready for me…the best testimony is to leave this goddamned world.”[52]

In 1974, Temple pioneers broke ground on the jungle acreage that would become the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project in Guyana, South America. This project, referred to as The Promised land – the same name as the agricultural projects of the Peace Mission 40 years previous – went from a small enclave of a few dozen people to a small town of just over 1,000 in a four year period. The center was a large communal open air pavilion which served multiple functions for the inhabitants: a dining area, a class room, a forum for Peoples Rallies and community meetings, and a space for entertainment both for themselves and for visiting guests.

In 1974, Temple pioneers broke ground on the jungle acreage that would become the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project in Guyana, South America. This project, referred to as The Promised land – the same name as the agricultural projects of the Peace Mission 40 years previous – went from a small enclave of a few dozen people to a small town of just over 1,000 in a four year period. The center was a large communal open air pavilion which served multiple functions for the inhabitants: a dining area, a class room, a forum for Peoples Rallies and community meetings, and a space for entertainment both for themselves and for visiting guests.

The Jonestown pavilion was also the structure where residents gathered to listen to Jones teach, lecture and harangue his followers. And of course, it was also here that the infamous White Night revolutionary suicide drills were rehearsed over the final months and then finally implemented on November 18th, 1978.

In addition, this small city had a school, a library, a communal laundry, a health clinic, a sewing factory, a soap factory, a brick factory and a sawmill. Its food preparation facilities featured a central kitchen, a bakery and herb kitchen. It also featured recreational facilities like play grounds with equipment for young children and toddlers and a basketball court for older teenagers. The housing consisted of communal cabins and dorms. There was a radio tower, barns and facilities to house various forms of livestock, and storage areas for foodstuff, medicines, and supplies.[53]

In addition, this small city had a school, a library, a communal laundry, a health clinic, a sewing factory, a soap factory, a brick factory and a sawmill. Its food preparation facilities featured a central kitchen, a bakery and herb kitchen. It also featured recreational facilities like play grounds with equipment for young children and toddlers and a basketball court for older teenagers. The housing consisted of communal cabins and dorms. There was a radio tower, barns and facilities to house various forms of livestock, and storage areas for foodstuff, medicines, and supplies.[53]

In contrast to group houses and communes of the Peace Mission and its predecessors – or even of Peoples Temple’s facilities in Redwood Valley, San Francisco and Los Angeles prior to 1974 – Jonestown stands alone as the only community designed and built by the organization itself with the group’s own funds, and inhabited solely by its people. Jonestown thus stands out as the pinnacle of the material, physical achievement of the cause.

Father Jehovia may have dreamed of one and Father Divine may have intended to eventually bring one into being one day, but it was Father Jones who made the utopian Divine city a physical reality.[54] It was truly his – and through him the entire movement’s – crowning achievement. And because of the tragedy of November 18, 1978, it has also become that movement’s defining event and its eternal legacy.

Conclusion: Jonestown and Woodmont and suffering to make the cause real.

“I represent Divine Principle, Divine Socialism, total equality, a society where people own all things in common, where there is no rich or poor, where there are no races, and so being Divine Principle, I will not pass away, but I shall stand throughout the endless ages of time.”[55]

“…the same with…everybody, every person who is willing to suffer to establish a Principle or a cause of Righteousness. You see, the willingness to suffer makes that particular Principle a reality. Isn’t that wonderful?”[56]

The lessons of the apostasies and their consequences on the Peace Mission of the 1930s and later on Peoples Temple in the 1970s are instructive. By examining the evidence, we learn that such apostasies called into question the validity of the principle on which the causes of Father Divine and Jim Jones stood. The overreaction of the two leaders to these dissenters and the subsequent negative publicity also raise questions of their overall judgment and hubris.

Faced with a single court judgment against him, Father Divine uprooted his entire New York base and operation, moved it out of state, and resettled it in a completely new location. In the process of starting all over again, he abandoned his dying wife and heavily-invested Promised Land schemes and properties. He changed the nature of his ministry and his followers operating in it in ways that insured that by doing so both would culminate in a slow extinction. Why? He did all that rather than pay a fine, because that would have threatened the validity and the dignity of the cause and the principle on which that cause stood.[57]

Jim Jones killed himself, his entire family, and his movement in Jonestown. Why? For him, that action maintained the validity and the dignity of the cause and the principle on which that cause stood. “We win when we go down” he said during the mass suicides.[58]

For Jim Jones and Father Divine, the actual lives of hundreds, if not thousands, of men, women and children followers and believers were expendable, whereas the cause and the principle were not. Possibly just as astounding is that the true believers in both movements supported those decisions, and in the case of the few remaining believers of the Peace Mission, they still do.[59]

Thus the vision of a vanishing Divine city, although unfulfilled in Father Divine’s lifetime and shared in theory by his wife and successor, Sweet Angel and by her rival and Divine’s reincarnation, Jim Jones, came to reality at Jonestown. There the vision, in all its stark literalness, was fulfilled.

Sources:

Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple, http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/.

Bender, Lauretta and M.A. Spaulding. “Behavior Problems in Children from the Homes of Followers of Father Divine.” Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, Vol. 91, No. 4 (April 1940), 460-472.

Black, E. The Reincarnations Of God: George Baker Jr. and Jim Jones as Fathers Divine. the jonestown report. 2009.

_____. Wives of God, Mothers of the Faithful: Edna Rose Baker and Marceline Jones as Mothers Divine. the jonestown report. 2013.

Boccella, Kathy. “At Gladwyne mansion, memories of Father Divine live on.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. April 17, 2011.

Divine, Mother. The Peace Mission Movement. New York: Anno Domini Father Divine Publications, 1982.

Erickson, Keith V. “Black Messiah: the Father Divine Peace Mission Movement.” Quarterly Journal of Speech, Vol. 63, 428-438 (December 1977).

Faithful Mary. “God”: He’s Just a Natural Man. Philadelphia: Universal Light, 1937.

“Father Divine.” Biography.com. A&E Network, 2013.

“Father Divine and the Peace Mission.” America and the Utopian Dream.

“Father Divine biography”. YourDictionary.com.

“Father Divine, Cult Leader, Dies; Disciples Considered Him God; Father Divine, Believed to Be God by His Followers, Is Dead.” The New York Times, September 11, 1965.

Father Divine’s International Peace Mission Movement, online here.

“‘Father Divine Is Dead’ Daddy Grace.” Baltimore Afro-American. June 1, 1957.

“Father Divine Is Dead; Was Messiah to Millions.” The Hartford (Conn) Courant. September 11, 1965.

“Father Divine. Order for Arrest. White Man Mobbed.” The Sydney Morning Herald. April 22, 1937.

“Father Divine’s Peace Mission: Hope For The Impoverished.” This Far by Faith. PBS.

“Father Divine Ready to Give Up to Police: Three of Followers Jailed in Stabbing, Beating Case.” The Florence (S.C.) Times, April 31, 1937.

Fauset, Arthur Huff, John Szwed and Barbara Dianne Savage. Black Gods of the Metropolis: Negro Religious Cults of the Urban North. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002.

FORMERLY THE PROPERTY OF REVEREND MAJOR JEALOUS “FATHER” DIVINE, AKA “THE MESSENGER”, THE PENULTIMATE DUESENBERG CHASSIS, Bonhams.com Auctions.

“From Azusa to Apostasy: The Father Divine Story.” The Old Landmark: Celebrating our Apostolic Heritage.

“‘God’ leaves behind ‘Divine’ dividends.” CultNews.com. June 13, 2003.

Hall, John R. Gone From the Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural History,New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers, 1987; reprint 2004.

Harris, Sara. Father Divine: Holy Husband. New York: Doubleday Publishing Company, 1953.

Jonestown Apologist Article Archive.

The Jonestown Massacre, culteducation.com.

The Jonestown Massacre, history1900s.about.com.

“Jonestown Suicides Shocked World.” Associated Press, March 27, 1997.

Kerns, Phil, with Doug Wead. Peoples Temple, Peoples Tomb. Plainfield, NJ: Logos International, 1979.

Krause, Charles A., and Laurence Stern. Guyana Massacre: The Eyewitness Account. New York: Berkley Publishing Corporation, 1978.

____, “The Shrine to Life.”

Maaga, Mary McCormick. Hearing the Voices of Jonestown. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1998.

Mabee, Carleton. Promised Land: Father Divine’s Interracial Communities in Ulster County, New York. Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press, 2008.

Melton, J. Gordon, “Universal Peace Mission of Father Divine,” in The Encyclopedic Handbook of Cults in America. New York: Garland Publishing Company, 1986.

Moore, Rebecca. Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2009.

____ and Anthony B. Pinn, Mary R. Sawyer, eds. Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2004.

Newton, Huey P. Revolutionary Suicide. New York: Random House, 1973.

Parker, Robert Allerton. The Incredible Messiah: The Deification of Father Divine. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1937.

“Police Seeking Father Divine. Leader of Cult Goes Into Hiding after Harlem Riot. Flees From ‘Heaven’ When Outsider Stabbed and Others Injured.” The Montreal Gazette, April 21, 1937

Reiterman, Tim, with John Jacobs. Raven: The Untold Story of the Rev. Jim Jones and His People. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1982.

Rothman, A.D. “Negro ‘Heaven’ Scandal.” The Argus, Melbourne, Victoria. Feb. 12, 1938.

“Rumors Father Divine Is Dead.” Jet Magazine, June 30, 1955, second column.

Schaefer, Richard T. and William W. Zellner. Extraordinary Groups: An Examination of Unconventional Lifestyles. New York: Worth Publishers, 2010.

Watts, Jill. God, Harlem, U.S.A.: The Father Divine Story. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1995.

Weisbrot, Robert. Father Divine: The Utopian Evangelist of the Depression Era who became an American Legend. Boston: Beacon Press, 1984.

_____. “Father Divine’s Peace Mission Movement,” in America’s Alternative Religions, ed. Tim Miller. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995.

West, Cornel, and Eddie S. Glaude Jr. African American Religious Thought: An Anthology. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2003.

White, Mel. Deceived. Old Tappan, N.J.: Spire Books, 1979.

Wikipedia. Apostasy.

_____, Communist Party USA.

_____, Father Divine.

_____, Marcus Garvey.

_____, International Peace Mission Movement.

_____, Jim Jones.

_____, Peoples Temple.

_____, Peoples Temple Agricultural Project (Jonestown).

_____, Peoples Temple in San Francisco.

_____, Edna Rose Ritchings.

_____, The Teachings of Father Divine.

_____, UNIA.

_____, Western Addition.

_____, Woodmont (Gladwyne, Pennsylvania).

YouTube, An American Castle – Woodmont the Alan Wood Jr. estate.

_____, Carleton Mabee 2009-09-20 Part 1 – Century House Hist. Soc., Rosendale, NY. Parts 2 through 7 also available.

_____, Exactly Who Was Father Divine?

_____, Father Divine, The March of Time, Harlem, New York, 1930s

_____, Former Alan Wood Jr. Estate – Woodmont in Gladwyne, PA

_____, The Jonestown Death Tape (FBI No. Q 042) (November 18, 1978)

Notes:

[1] Excerpt from a speech by The Messenger aka “Father” and “God” (Father Divine) to his small core house/congregation in its pre-Peace Mission phase on Broome Street in Manhattan, New York in 1917, and recorded from a post-Christmas speech on September 26, 1931, and reprinted in The New Day, June 29, 1974.

[2] Robert Parker, The Incredible Messiah: The Deification of Father Divine (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1937), 284.

[3] From the 1917 speech by Father Divine.

[4] For an overview of Father Divine’s International Peace Mission movement, see Arthur Huff Fauset, John Szwed and Barbara Dianne Savage, Black Gods of the Metropolis: Negro Religious Cults of the Urban North (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002); J. Gordon Melton, “Universal Peace Mission of Father Divine,” in The Encyclopedic Handbook of Cults in America (New York: Garland Publishing Company, 1986); and Robert Weisbrot, “Father Divine’s Peace Mission Movement,” in America’s Alternative Religions, ed. Tim Miller (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995). For a perspective of the declining Movement led by Mother Divine in 2005, see “The Father Divine Movement” in Richard T. Schaefer and William W. Zellner, Extraordinary Groups: An Examination of Unconventional Lifestyles (New York: Worth Publishers, 2010).

[5] Wikipedia, Woodmont (Gladwyne, Pennsylvania).

[6] On Father Divine’s Woodmont Mausoleum, The Shrine to Life, see Libertynet.org, “The Shrine to Life.”. On The Father Divine Library, see The Ground Breaking Ceremony for FATHER DIVINE’S Library Took Place at the Liberty Plaza, The Mount of the House of the Lord, August 12, 2008, 10 AM.

[7] For more on Mother Divine, see Edna Rose Ritchings; E. Black, Wives of God, Mothers of the Faithful: Edna Rose Baker and Marceline Jones as Mothers Divine; and Kathy Boccella, “At Gladwyne mansion, memories of Father Divine live on.” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 17, 2011 (online here). Mother Divine’s exact age is not known, although most sources give the year of her birth as 1925.

[8] On classifications of the Peace Mission, see note 4 above.

[9] On Father Divine ordering sex off the face of the earth, see Sara Harris, Father Divine: Holy Husband (New York: Doubleday Publishing Company, 1953), 96-115; and Mother Divine, The Peace Mission Movement (New York: Anno Domini Father Divine Publications, 1982), 52.

See also Libertynet.org, “Question: “How Will the Earth Be Replenished and Continue to Exist If the Population Thereof Ceases to Increase?” and “Overpopulation, The Cause Unrestrained Cohabitation – Sex”.

On the Peace Mission’s position on proselytizing for new members, see Mother Divine, The Peace Mission Movement, 9.

[10] On the Peace Mission’s roots in the obscure Baltimore, Maryland-based new religious movement of Samuel Morris in his guise as Father Jehovia at the turn of the 20th century, see E. Black, The Reincarnations Of God: George Baker Jr. and Jim Jones as Fathers Divine (2009); Harris, Father Divine: Holy Husband, 13-16; and Jill Watts, God, Harlem, U.S.A.: The Father Divine Story (Berkeley, University of California Press, 1995), 27- 31.

For a Pentecostal Christian take on the rise of Father Divine from Father Jehovia’s group, see “From Azusa to Apostasy: The Father Divine Story.” The Old Landmark: Celebrating our Apostolic Heritage.

[11] See the Peace Mission teaching that “If there are no deaths, there need be no births. Therefore when people cease to propagate, they will cease to die,” in Mother Divine, The Peace Mission Movement, 52.

[12] Robert Weisbrot, Father Divine (Boston: Beacon Press, 1984), 33.

[13] “Father Divine biography” at “Father Divine biography”, YourDictionary.com.

[14] See The Father Divine Project and www.peacemission.info for more on Father Divine’s and his followers’ assertions about him and his ministry.

[15] For concerns about the children of the Peace Mission, see Lauretta Bender and M.A. Spaulding, “Behavior Problems in Children from the Homes of Followers of Father Divine,” Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, Vol. 91, Issue 4 (April 1940), 460-472; also Harris, Father Divine: Holy Husband, 142-161.

For the UNIA of Marcus Garvey concern and statement on race suicide as advocated by the Peace Mission. see Cornel West and Eddie S. Glaude Jr., African American Religious Thought: An Anthology (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2003), 572.

[16] For more on the Peace Mission’s Harlem headquarters in the 1930s, see Robert Allerton Parker, The Incredible Messiah: The Deification of Father Divine (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1937), 109. See also, “Reverend Major Jealous ‘Father’ Divine in Harlem” from The Harlem World Magazine. The building that housed Father Divine’s headquarters is now a parking lot. The entire area was razed shortly after World War II, and today a series of high-rise housing projects has taken its place.

[17] On the Peace Mission’s voter registration and literacy drives and campaigns, see Harris, Father Divine: Holy Husband, 196-208; and Watts, God, Harlem, U.S.A., 131-132, 136.

[18] For more on the Peace Mission’s aggressive overtures to and recruitment from the UNIA of Marcus Garvey, see Watts, God, Harlem, U.S.A., 113 and 115; Robert Weisbrot, Father Divine (Boston: Beacon Press, 1984), 108, 191-194; and West and Glaude, African American Religious Thought, 572-581.

[19] For more of Father Divine and the 1930s Peace Mission ties and alliance with the Communist Party USA, see Harris, Father Divine: Holy Husband, 189-192; Watts, God, Harlem, U.S.A., 119-121, 135, 139; and Weisbrot, Father Divine, 148-152.

[20] On the Promised Land of Father Divine, see Carlton Mabee, Promised Land: Father Divine’s Interracial Communities in Ulster County, New York (Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press, 2008).

[21] For more on the Delight Jewett scandal, see Watts, God, Harlem, U.S.A., 147-151, 156; Mabee, Promised Land, 129, 132-133; and A.D. Rothman, “Negro ‘Heaven’ Scandal,” The Argus, Melbourne, Victoria. Feb. 12, 1938.

For more on John Wuest Hunt, see Watts, God, Harlem, U.S.A, 124, 144-151 and 169-170; and Mabee, Promised Land, 98, 100, 103, 189, 195, 129-134.

[22] For more on the vicious attack on the processor server Harry Green and his two companions Joseph Devove and Paul Camora by the Peace Mission, see Wikipedia, Father Divine; also “Police Seeking Father Divine. Leader of Cult Goes Into Hiding after Harlem Riot. Flees From ‘Heaven’ When Outsider Stabbed and Others Injured.” The Montreal Gazette, April 21, 1937;

“Father Divine. Order for Arrest. White Man Mobbed.” The Sydney Morning Herald. April 22, 1937; and “Father Divine Ready to Give Up to Police: Three of Followers Jailed in Stabbing, Beating Case.” The Florence (S.C.) Times, April 31, 1937.

One is reminded in this 1937 incident of sudden vigilante violence towards an assumed threat to their leader of the attack on Congressman Leo Ryan, first by Ujara (Don Sly) in Jonestown and then his assassination at the Port Kaituma air strip, Guyana over 40 years later.

Also instead of using the melee as cover to flee the law enforcement authorities by trying to hide behind furniture in a Peace Mission extension basement and “invisabilize himself,” as Father Divine did when they caught up with him, Jim Jones and his followers, stood their collective ground in the immediate wake of the murder of Congressman Ryan. With nowhere to go and no way to get there, they collectively escaped capture through committing revolutionary mass suicide.

[23] On Mother Peninnah Divine’s illness, hospitalization and press coverage, see Mabee, Promised Land, 116-117; and Watts, God, Harlem, U.S.A., 151-152.

[24] See Faithful Mary, “God”: He’s Just a Natural Man (Philadelphia: Universal Light, 1937) and Harris, Father Divine: Holy Husband, 79. Although Faithful Mary would go on to recant her claims as a price to pay for re-admittance into the Peace Mission, her allegations were later sustained by subsequent Peace Mission apostate accounts, including those by Mr. and Mrs. John W. Hunt, Heavenly Love, and Valerie St Valor.

Faithful Mary’s birth name was Viola Wilson. She was one of 16 children born to a family in the rural south and she migrated up to the New Jersey, New York area as a young adult, where she found that job prospects for Black females in the urban areas were few and far between. According to her own written account, she engaged in alcoholism and prostitution before being admitted into a Peace Mission extension in the early 1930s, where she cleaned up. That was where she caught the eye and the interest of Father Divine. Her ascent up the ladder in the Peace Mission was rapid, and within months she was on Divine’s secretarial staff and given many duties and responsibilities within the movement.

She soon was Female secretary #1 and helped pioneer the purchase and occupation of lands and businesses in the Promised Land. She also became a trusted aide to Mother Penny Divine and, as she confessed upon defecting from the Peace Mission, Divine’s lover and mistress.

Of interest from a sociological point of view, Father Divine’s appointment of a reformed and former alcoholic prostitute such as Faithful Mary along with John W. Hunt aka “John the Revelator,” the scion of a wealthy white family, to be organizational equals as his top level secretaries in the mid 1930s affirms his espoused sense of egalitarianism.

[25] On the Peace Mission apostate Browns’ lawsuit against Father Divine and his disproportionate and extreme response to the judgment against him, see Harris, Father Divine: Holy Husband, 84-95; Mabee, Promised Land, 110, 152-153, 157-158, 199-203; and Watts, God, Harlem, U.S.A., 61, 155, 160, 165-166.

Having first filed their claim in 1937, the Browns never relinquished their request for reimbursement from Father Divine and the Peace Mission movement. As the decades passed and Father refused to pay them, Verinda Brown continued to be bitterly opposed to the movement.

[26] Father Divine quoted in The New Day, June 7, 1952.

[27] On the negative and untimely fatal effects on the “Promised Land” Peace Mission Agricultural Project over time because of the abandonment of New York by Father Divine, see Mabee, Promised Land, 199-203 and 207.

[28] On the arbitrary move to Pennsylvania and its ultimately deleterious effects on the whole movement over time, see Mabee, Promised Land, 199-203 and 207.

[29] On Father Divine’s cavalier and vindictive attitude concerning his decision to abandon New York over a decade, see Harris, Father Divine: Holy Husband, 93-96, and Mabee, Promised Land, 203.

[30] On John Devout’s purchase of Woodmont as a gift to Father and Mother Divine, see Mabee, Promised Land, 155-156, and Watts, God, Harlem, U.S.A., 171.

[31] For more on the significance of the Hunt family to the Peace Mission movement, see Harris, Father Divine: Holy Husband; Mabee, Promised Land; and Watts, God, Harlem, U.S.A.

The Woodmont Mansion was not the only fantastic gift from the Hunts to Father Divine. In the 1930s they also gave him his world famous penultimate Duesenberg Throne car. See Bonhams.com Auctions. Although she kept Woodmont, Mother Divine ultimately sold the classic Duesenberg in the early 1980s.

[32] On Father Divine’s physical decline due to advancing age in the latter half of the 1950s, see “Rumors Father Divine Is Dead,” Jet Magazine, June 30, 1955 (second column); and “‘Father Divine Is Dead’ Daddy Grace.” Baltimore Afro-American. June 1, 1957.

Of interest here are the parallel efforts of a nurse and the nurse’s aide, Marceline and Jim Jones, to build an anti-racist social service-oriented Christian ministry in the latter 1950s and simultaneously provide state of the art nursing home care for the elderly.

In light of Jim Jones firm and openly expressed conviction that he had come to take the 70ish Father Divine’s place at the head of the Peace Mission movement, an interesting question arises: Is it possible, that he and his wife may have built their nursing home business partially with the idea of placing the elderly Father Divine, into one of them? Had that happened, it would have been a major and defining coup for the young Jones and his claim to be the successor to the leadership of the Peace Mission.

That such a plan may have been in the works – and or at least considered possible – is the fact that Jim Jones stated in 1974 that during one of his last face-to-face encounters with Father Divine in 1959, he had offered, and Father Divine had accepted an offer to leave Woodmont to come and live with him and Marceline, but that Divine’s secretarial staff – led by Mother Divine – physically prevented the elderly Father Divine from doing so.

From a tape transcript of Jim Jones’ words: “(Father Divine) looked at me (Jim Jones) and he said, ‘Whatever mantle I have, it’s with you… Don’t die, like I’m going to in here.’… I’ll never forget that, as long as I live. That’s what he told me in Philadelphia… I said, ‘You ought to come with me.’ And he started to walk, like a poor old little old man, he started to walk, and those secretaries put a circle around him. And that’s the last time I saw him alive. Because he wanted to go. I said, ‘Come and go with me, and we’ll be like it was when you were free’,” i.e. like in the Peace Mission heyday of the 1930s.

[33] See Harris, Father Divine: Holy Husband, 319-320.

[34] On the death of God, Father Divine, and the media coverage of it, see “Father Divine, Cult Leader, Dies; Disciples Considered Him God; Father Divine, Believed to Be God by His Followers, Is Dead,” The New York Times, September 11, 1965; and “Father Divine Is Dead; Was Messiah to Millions.” The Hartford (Conn) Courant. September 11, 1965.

[35] On Revolutionary Suicide as coined by Black Panther Party founder and leader, see Huey P. Newton, Revolutionary Suicide (New York: Random House, 1973), 3-7, 328-333.

On the suicidal implications of the actual theory and practice of the Peace Mission, see Harris, Father Divine: Holy Husband, 116, 142, 310-320.

Jim Jones uses the term during the event of November 18, 1978 to describe the event that he was overseeing. See Rebecca Moore, Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2009), 101. Yet the term “Revolutionary suicide” or a type of political martyrdom can also be seen to characterize the entire movement, its leaders and its followers from its inception under Father Jehovia to Jonestown and on to the few, aged Peace Mission relics at Woodmont.

The decisions that Samuel Morris made to become Father Jehovia and that George Baker Jr. made when he decided to follow him and became “the messenger” and “God in the sonship degree” and ultimately “Father Divine” can all be seen as forms of revolutionary protest of and a form of suicide in regards to the world of racism that they were confronting and opposing.

Likewise, according to her own account, when the current Mother Divine was simply Edna Rose Ritchings in far away Canada, she made radical, unusual and revolutionary life-changing decisions that ultimately divorced her from her birth family and led her to the USA and into her role within the Peace Mission, first as Father Divine’s secretary and then as his wife. This was done is spite of the 50-year age gap between them during a time when such intergenerational relationships were frowned upon and interracial marriage was punishable by prison terms and fines in most places. She martyred her youth, and – one might argue – her reputation for the cause.

Mother Divine’s incremental revolutionary suicidal decisions on behalf of the cause led her to the overall leadership of a Peace Mission that has been in steady decline throughout her watch.

[36] For accounts of the scene at Jonestown in the aftermath of the mass suicides and murders, see “Jonestown Suicides Shocked World” Associated Press, March 27, 1997; The Jonestown Massacre, culteducation.com; and The Jonestown Massacre, history1900s.about.com.

[37] See the accounts in Charles A. Krause and Laurence Stern, Guyana Massacre: The Eyewitness Account (New York: Berkley Publishing Corporation, 1978); Mel White, Deceived (Old Tappan, N.J.: Spire Books, 1979; and Phil Kerns, with Doug Wead, Peoples Temple, Peoples Tomb, (Plainfield, NJ: Logos International, 1979) for their cursory and passing coverage of the Peace Mission /Peoples Temple connection.

The Peace Mission /Peoples Temple connection has always been included as part of the Peoples Temple story, but rarely has it been given central contextual emphasis, due to both the horrendous and jarring nature of the event of November 18, 1978 itself, and the personal unfamiliarity of authors and researchers writing on the Temple, with the subject of Father Divine and the Peace Mission.

The movie Guyana Tragedy: The Story of Jim Jones popularized the extensive and long-term Peace Mission /Peoples Temple connection as a one-time fateful encounter between the two men.

The accounts of Tim Reiterman (with John Jacobs, Raven: The Untold Story of the Rev. Jim Jones and His People (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1982)) and John R. Hall (Gone From the Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural History (New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers, 1987; reprint 2004)) added more contextual gravitas to the importance of the Peace Mission /Peoples Temple connection.

Later, C. Eric Lincoln (in Rebecca Moore, Anthony B. Pinn, Mary R. Sawyer, eds. Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2004)) would write “Daddy Jones and Father Divine” as a more substantive account from a black perspective. This article also connected Sarah Harris’ prediction of mass suicides for Father Divine to the actual mass suicides for Jim Jones.

[38] Father Divine being the same God, but in the First Body.

[39] Jim Jones, Q 1059-1 (1974).

[40] On how Father Divine and Jim Jones became the same God, see The Reincarnations Of God: George Baker Jr. and Jim Jones as Fathers Divine by E. Black.

[41] See The New Day, July 26, 1958 (p. 16-17), August 2, 1958 (p. 18-21), and August 30, 1958.

[42] For more on the former Albert Pike Memorial Scottish Rite Temple building, see Peoples Temple San Francisco, and The Museum of the City of San Francisco.

[43] For more on the political connections of Peoples Temple in San Francisco all the way up to the presidency, see Hall, Gone From the Promised Land, 161-171; Moore, Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple, 29-31, 38; Reiterman, Raven, 150-155; and Peoples Temple in San Francisco.

[44] For more on the negative press on Jim Jones and the threat of investigations, see Les Kinsolving’s Original Exposés in the Jonestown Apologist Article Archive.

[45] This is why, in their 20-year acrimonious debate for leadership of the cause, Mother Divine and Jim Jones focused on reiterating their respective qualifications to lead it. Mother Divine emphasized that she was Father’s “Spotless Virgin” and the reincarnation of the biblical “Virgin Mary” and of Peninnah, the first “Mother Divine.” Jim Jones emphasized that he was “Principle” and, as such, he was the reincarnation of Buddha, Jesus Christ, Lenin and Father Divine. Both tore down the other’s individual personality, as opposed to challenging the other on the fundamentals or the rightness of the cause, as they both agreed on that. They simply tried to portray the other as unfit to lead it.

[46] Both the Peace Mission and Peoples Temple used coercive and physical discipline on members, regardless of age and rank, to ward off bad or counter group behavior and enforce adherence to and compliance with organizational codes of conduct.

On Peoples Temple’s internal coercive practices and apostates (defectors), see Hall, Gone From the Promised Land, 45, 117, 119-120, 137-138 and 211; Moore, Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple, 31-35; and Reiterman, Raven, 259-261.

[47] The apostate “Eight Revolutionaries” of 1973 were, Jim Cobb, Wayne Pietila, Tom Podgorski, Lena Flowers, John Biddulph, Vera Biddulph, Teri Cobb and Mickey Touchette. All of them were young, Black and White interracial couples, some of whom had served as Temple bodyguards and/or Planning Commission members who were, as a group, disaffected by a combination of frustrations in dealings with Jones’ all-white, mainly female leadership group, their personal conflicts with the Temple’s prohibitions against sexual intercourse, drugs and alcohol use, and the disconnect that they felt between the Temple’s ideology and practice of Divine Socialism.

For more on the apostasy of Al and his wife Jeannie Mills, see Hall, Gone From the Promised Land, 178-181,184-185, 210-211, 216, 219, 223, 225, 245, 304 and 283; Moore, Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple, 58-59, 61-62, 66, 78, 81, 90, 135, and 138-139; and Reiterman, Raven, 286, 329, 340, 351, 353-354, 408, 477, and 575.

For more on the apostasy of Bob Houston and his wife Joyce Shaw, see Hall, Gone From the Promised Land, 129 and 139; Moore, Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple, 38, 58, and 88; and Reiterman, Raven, 1-3, 296-301, 377-378, and 578.

For more on the apostasy of Grace Grech Stoen and her husband Timothy Stoen, see Hall, Gone From the Promised Land, 184-185, 200-201, 211-213, 222, 225, 245, and 268; Moore, Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple, 37-38, 58-64, 66, 72, 76-77, 80-83, 90-92, 94, 111, 126, and 140; and Reiterman, Raven, 286-293, 316-320, and 323-324.

[48] On Jim Jones first introducing the concept of revolutionary suicide for the cause to counter apostasies, see Hall, Gone From the Promised Land, 132-138; and Moore, Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple, 37-38.

[49] On Jim Jones deciding on Guyana for the location of his Divine city, see Hall, Gone From the Promised Land, 132-138; Moore, Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple, 38; and Reiterman, Raven, 237.

[50] On other possible locations which were discussed and explored, see Petition to Move to the Soviet Union.

[51] On Father Divine threatening to commit suicide in response and reaction to a racially-divisive incident that occurred among his followers during a communal meal in an earlier part of his ministry, see The New Day, June 29, 1974, p. 18.

Of interest and particular import is the fact that the quotations from The New Day magazines above were transcribed from earlier speeches of Father Divine and then reprinted in 1974. Thus Father Divine’s teachings and viewpoints on the Promised Land, the vanishing city, his threat of suicide, etc. were available to Jim Jones, an avid reader and student of the writings and speeches of Father Divine, for his perusal, inspiration and contemplation during the height of his ministry as leader of Peoples Temple.

The years 1973 and 1974 are important in Peoples Temple history as both the concepts of and the need for revolutionary suicide for the cause and of a city to be built in Guyana were articulated by Jim Jones to his inner leadership core.

[52] Jim Jones, Q 042 (Death Tape), reprinted in Mary McCormick Maaga, Hearing the Voices of Jonestown (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1998), 154ff.

[53] For more on Jonestown as a town or small city, see Moore, Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple, 43, 45-54, 56, and 70-71; and Reiterman, Raven, 240, 242, 246, 275, 276-277, 311, 313, 322, 345-347, 392, and 417.

[54] The Peace Mission version of the Promised Land was located in and spread out through the rural areas of upstate New York and did not consist of a one movement-built city as was the eventual case with Jonestown.

Father Divine’s followers built edifices, such as add-ons and addendums to pre-existing structures, as well as individual structures like an occasional barn, home etc in some of the various towns and farms in Ulster County, New York. See Mabee, Promised Land, 45. In the Peace Mission, the issue that the leader drew a principled line in the sand with apostates was whether or not to pay the Browns a reimbursement fee of $4,476.

[55] Jim Jones, Q 1059-1 (1974).

[56] Mother Divine, The Peace Mission Movement, 100.

[57] Maaga, Hearing The Voices Of Jonestown, 154ff.

[58] In Peoples Temple, the issue that the leader drew a principled line in the sand with apostates was the John Victor Stoen custody case.

[59] In his 1937 biography of Father Divine, who was then at the height of his career, Robert Parker concluded with the statement and prediction that: “[Father Divine] had imagined the drama; he had assumed the leading role; he had staged the whole production on this lavish scale. Now he must act it out to the end, no matter what that [end] might be, whether it were to come with catastrophic violence, or with the slow torture of disillusion” (The Incredible Messiah, 302).

Over 70 years later, we find that, while the few remaining Peace Mission members who identify as Divine followers are coming to a slow end, those who followed Divine’s erstwhile successor Jim Jones fulfilled Parker’s prediction of a catastrophic and violent end.