An examination of the legacies of Peoples Temple and the Peace Mission[1]

1 The Struggle for Social justice in the USA

2 The Peace Mission and Peoples Temples as Subversive and Non-conformist Social Justice organizations

3 The Grandparent Organizations for the Cause of Radical Social Justice

4 Forty Years after Jonestown: The Social Justice Aftermath and the Legacy of the Final Mass Die-In

5 Conclusion: To live and Die for the Cause of Radical Social Justice

7 Notes

Preface

The first two decades of the 21st century have seen an increase in the number of social activist movements in the USA.[2] Numerous groups outside mainstream organizations with a wide range of causes – ranging from animal rights, protests against the ongoing US wars in central Asia and the Levant, AIDS activists, alternate sexuality and feminist activist, gun control advocates and environmental activists – have joined more recent radical groups like Occupy, Antifa, BlackLives Matter and the Movement for Black Lives in a brilliant and often contentious cacophony in the ongoing fight for social justice.[3] For some, the failure of the Democratic Party to secure the presidency in 2016 and the election of billionaire businessman Donald Trump signaled a dangerous turn towards neo-fascism. For them, the result of the election was a call to renew and deepen their commitment to social justice, resulting in an internal clash of cultures reminiscent of the turbulent 1960s.[4]

In the midst of this resurgence and proliferation of social justice groups, this year marks the fortieth anniversary of the cataclysmic end of an earlier, problematic social justice group, Peoples Temple.[5] It is doubtful that any of the various activist and partisans in the radical social justice milieu will observe or commemorate this anniversary in any way, as the legacy of Peoples Temple as a social justice group is fundamentally marred by its tragic ending.

Another anniversary in the annals of social justice struggle that has gone unmentioned and overlooked in 2018, the death of Edna Rose Ritchings-Baker. Mrs. Baker had succeeded her late husband, George Baker Jr., aka Father Divine, as the leader of an even earlier social justice group, the International Peace Mission Movement. Edna Rose Ritchings-Baker was known in the Peace Mission as both Sweet Angel and Mother Divine.[6]

Another anniversary in the annals of social justice struggle that has gone unmentioned and overlooked in 2018, the death of Edna Rose Ritchings-Baker. Mrs. Baker had succeeded her late husband, George Baker Jr., aka Father Divine, as the leader of an even earlier social justice group, the International Peace Mission Movement. Edna Rose Ritchings-Baker was known in the Peace Mission as both Sweet Angel and Mother Divine.[6]

Although not widely appreciated as such, the Peace Mission and Peoples Temple were radical social groups, though organized as Christian churches, whose very raison d’etre was the cause of racial and economic social justice. The Peace Mission, founded in 1932, and Peoples Temple, which opened in 1955, defined themselves as institutions of “spiritual” and/or “radical democracy” dedicated to the cause of bringing into reality “the universal brotherhood of man.” The Peace Mission, though still operative at its Philadelphia, Pennsylvania area headquarters, is in steep decline, its few remaining activists in their 80s and 90s, the movement’s heyday having been almost a century ago. Peoples Temple Christian Church formally disbanded in March 1979.[7]

Although separate and distinct organizations, the Peace Mission and Peoples Temple have been linked together as expressions of a heterodox, apocalyptic radical movement for social justice with roots in the late 19th century. Both groups made their mark in the 20th century as specialized, high intensity and totalistic groups fanatically wedded to an ideological cause of racial and economic justice. The two groups are further associated through the personal and decade-long interactions between their respective founders. Both Father Divine and Jim Jones were zealous and determined tacticians and social justice warriors. Despite their very different backgrounds, they shared an ideology of the ultimate and successful strategy in compelling their most committed followers to live the ideological goals of the groups they created, goals that the followers then made their own and tried to fulfill up to and including death.[8]

Prefiguring such 21st century social activist groups like Black Lives Matter and the Movement for Black Lives by decades, the Peace Mission and Peoples Temple – most active in the 1930s and 1970s, respectively – operated in the African-American community, were composed of African-American majorities, and were known for boldly challenging systemic racism in the US and beyond. This paper examines both the similarities and the differences of Father Divine and Jim Jones as social justice activists and leaders, their respective utopian, social justice intentional communities, and their possible legacy.

The Struggle for Social Justice in the USA

Social Justice is understood as justice in terms of the distribution of wealth, opportunities, and privileges equitably and fairly within a society. The term social justice warrior, which has recently come into vogue, defines those who acknowledge the existence of racism, sexism, classism and other forms of bigotry, and who live their lives countering such injustices while seeking to replace them with social fairness and balance. It is this definition that applies to the subjects of this paper and the groups they founded and led.[9]

The battle to define civil rights and social justice for its inhabitants, collectively known as Americans, is codified in its founding declaration. The American Declaration of Independence proclaims the right to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness”; the challenge in the intervening years has been to define, expand and apply that declaration.[10] For many who find that their rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness are circumscribed – either as an individual or as a member of an aggrieved subgroup – the struggle to realize and achieve them is often long, bitter, and continuous. That struggle to realize and achieve social justice is referred to as the Cause.[11]

The Peace Mission and Peoples Temple as Subversive and Non-conformist Social Justice Organizations

19th century roots

In the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, the victorious Union forces occupied the defeated former Confederated States of America. The formerly-enslaved Africans of the Confederacy were granted emancipation, and slavery was abolished, except for those in prison. A period of a decade or more of social progress saw the exponential rise of economic, political and social progress of the African descendent populations throughout the recently-reunited nation. Especially in the South, this period came to be known as the Reconstruction Era.[12]

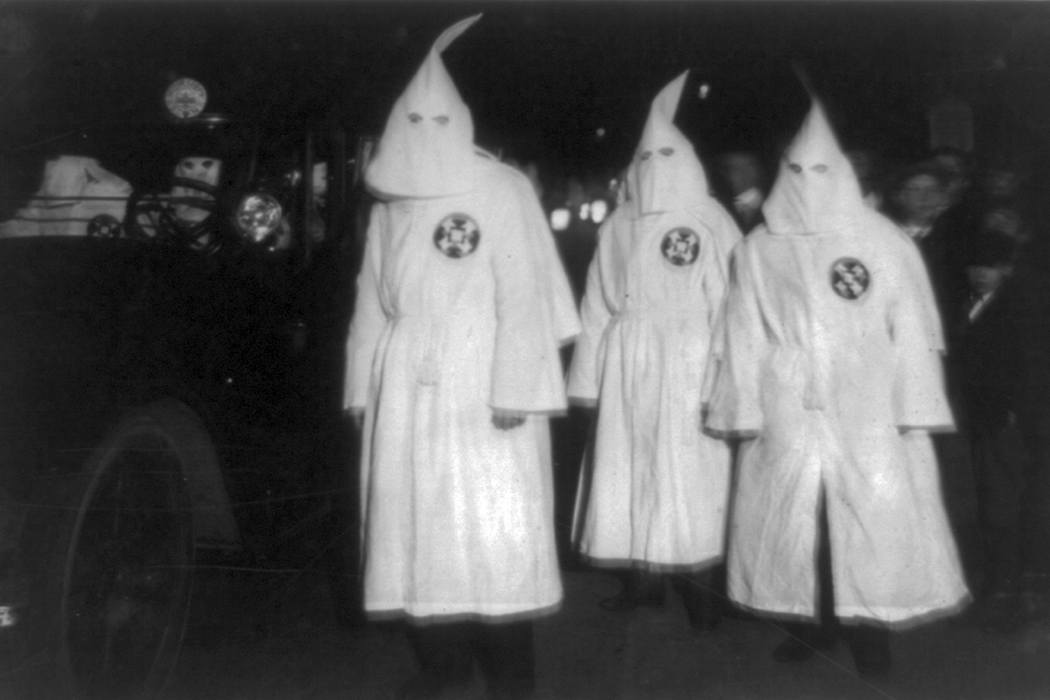

The progress of Reconstruction did meet with resistance, however. A combination of former plantation owners, urban business owners, displaced confederate soldiers, and others eventually regained much of their pre-war political strength and began re-subjugating black populations of the South through laws and social practices known as Jim Crow. Often enforced through the creation and growth of a white terrorist death squad known as the Ku Klux Klan, the de jure segregation of Jim Crow soon effectively crippled or reversed much of the strides towards justice and inclusion of the recently-emancipated formerly-enslaved populations across the late 19th century American South.[13]

The progress of Reconstruction did meet with resistance, however. A combination of former plantation owners, urban business owners, displaced confederate soldiers, and others eventually regained much of their pre-war political strength and began re-subjugating black populations of the South through laws and social practices known as Jim Crow. Often enforced through the creation and growth of a white terrorist death squad known as the Ku Klux Klan, the de jure segregation of Jim Crow soon effectively crippled or reversed much of the strides towards justice and inclusion of the recently-emancipated formerly-enslaved populations across the late 19th century American South.[13]

Also during this period several utopian, communist communities flourished. Most, but not all, were comprised of Americans of European descent, many of them newly-arrived immigrants. These immigrants included Jewish and other minority populations escaping the various anti-socialist repressions among the European imperial monarchies. Whether native-born, immigrant, European or African descendent, all mixed in a cauldron of humanity which expected the fulfillment of the Declaration of Independence’s promise to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”[14]

Father Divine and Jim Jones as Subversive and Non-conformist Social Justice Warriors

George Baker, Jr. was born in the nation’s South in the late 1870s, during the period of postwar Reconstruction. His parents were former slaves, and the social and living conditions of his family were at the very bottom of the nation’s socio-economic indices. But he was not content to accept these conditions and set out as an adult to make a new life for himself.

Baker’s quest for social justice was met with the very real obstacles of physical stature, race, class and region of the time period. Most avenues for a radical and successful transformation of his life’s circumstance were either not readily available to him or completely closed. He ultimately found solace and a methodology for achieving his social, political and cultural goals by becoming a master in the subjective world of faith and self-improvement in the subculture of heterodox spiritualities on the margins of the urban cults and new religions of the Black community.[15]

As founder and leader of the International Peace Mission Movement, George Baker eschewed his previous identity and presented himself to his followers and to the world as Father Divine. This title and name confirmed the death of Baker’s prior self and announced his rebirth as the embodiment of Principle on the human level or plane of existence. Accepting Father Divine as guru, spiritual advisor and/or God served as the signature of his ministry. The intentional communal family/community that he created recognized him as the physical embodiment of the Principle of social justice. In this intentional utopian community Baker/Divine was the begetter of the new consciousness that sustained and maintained it.[16]

As Father Divine, Baker achieved not only disciplined mastery over his own immediate life but also over those of tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of others on five continents. Many of those whom he called his “children” were of European descent, and most were born into life circumstances that were higher on the social indexes than Baker. Some were even highly affluent. All openly accepted Father Divine’s reinterpretation of reality and entered into a codependent relationship with him as their guru, spiritual adviser and God, gladly relinquishing their material wealth to the collective over which Divine presided.

This allowed Divine to preside as the spiritual head of a communal socialist collective that ran a string of businesses, including diners and rental properties serving inner city ghettos in the midst of the Great Depression. It also permitted him to live the material life of a billionaire steel magnate, complete with servants, a custom-made limousine, and a multi-acre hilltop manor-estate in an exclusive, suburban Philadelphia neighborhood.

During the 1930s, Father Divine chastised both the church world and the country for not living up to their promises to their worshipers and country, respectively. Divine and his propagandists proclaimed that he was the only one who could provide life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness – i.e. social justice – for all through his Peace Mission Movement. Although the Peace Mission proclaimed fraternity with the Communist Party of the USA in the cause of social justice, by the Cold War years of the 1950s, it muted such open support. It assumed the outward veneer of an anti-communist and patriotic group, even as it simultaneously proclaimed that Father Divine had the ultimate control of the nation’s nuclear weapons, and continued to press for reparations for the descendants of slaves.

The Peace Mission Movement’s successes in feeding, housing and clothing its largely inner city followers during the 1930s were impressive. Nevertheless, the Mission’s strident proclamation of its founder and leader as God with the power to heal the sick and to raise the dead, its radical social posture of immediate and complete integration and denial of the very concept of race, its insistence on male and female equality, and the complete separation of the sexes while positing its stated goal of banishing sexual reproduction, marginalized it in the overall movement for social justice and civil rights.

James Warren Jones was born in the rural Midwest during the Great Depression era that was marked by increased levels of deprivation for the working and less affluent white masses across the US. This deprivation and disenchantment with the American promise underscored for many the hypocrisy of the promise of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness as proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence. Jones’ birth state of Indiana was also the center for the 20th century renaissance of the KKK.

Much has been written about Jones’ youth and early life by various biographers. What is common to all these accounts is an understanding that young Jones was a hyper sensitive youth who early on developed a keen sense for discerning social injustices. He spent much of his time dealing with cognitive dissonance caused by trying to rationalize and overcome the contradiction of being a poor and white man in a nation in which whiteness was promoted as being of intrinsic worth. His attempts to understand this and other contradictions led him to enter into a strained relationship with various local expressions of the Christian Church, aspects of which he both embraced and rejected.

Jones’ teenage years coincided with the nascent Cold War which followed World War II. This international ideological conflict between the Free World, led by the US, and the Communist World, led by the Soviet Union, found its greatest differences in the articulation of social justice issues, with each side defending its own efforts to promote them and accusing the other of being the enemy of that noble appeal.

Ever cognizant of the hypocrisies and contradictions of the nations involved in the Cold War – as well as of the churches – Jim Jones decided to enter the Christian ministry during the years that coincided with the Korean War. He eventually founded his own church in 1955. Like George Baker, Jr. almost half a century before him, Rev. Jones began a quest to transform personal, political and spiritual circumstances by creating a new reality as the founder and leader of an social activist church community in which he was recognized for the sensitive and caring person he claimed to be and as the physical embodiment of the Principle of social justice.

The church he named Peoples Temple.[17] As the begetter of the new consciousness that sustained and maintained this social activist church community, he became known as Father Jones. The roles of God, Jesus Christ and Holy Prophet – as understood in the normative Christian tradition – became merged first in the actual practice and then in the person of Rev. Jones. He became the living embodiment of the Temple’s mission and purpose, adopting children from several ethnicities, in addition to having a natural born son.

The goal of Peoples Temple was to create and foster of an intentional utopian community of social justice guaranteeing life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness to its members. This community would be the ultimate realization of social justice, and in transforming himself through disciplined mastery over his own life circumstances, he would inspire and cause others to achieve life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, regardless of age, gender, race and class.[18]

The Grandparent Organizations for the Cause of Radical Social Justice[19]

While mainstream liberal Christian churches – both Black and white – and interracial social activist organizations like the NAACP characterized and shaped the central mass struggle for racial and social justice, the Peace Mission and Peoples Temple occupied subversive and non-conformist social justice space on the margins of civil and religious culture through much of the 20th century. Based on a marginal but exclusive model in which “universal truth and justice” was embodied in their respective founders and leaders, the Peace Mission and Peoples Temple often derisively dismissed the mainstream groups as hopelessly ineffectual.[20] These two communities directly targeted and challenged what their leaders pointed out as the chief obstacles to every American achieving their rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness – namely racism, sexism, classism and other forms of bigotry – and sought to make America into an actual utopia, known in both groups as “the Promised Land.”[21]

Long before the mainstream Civil Rights Movement and in the midst of Jim Crow and KKK racial violence, organizing from a space he had intentionally integrated in historically-racially segregated suburbia, Father Divine required that his followers as well as those who occupied leadership positions live interracially in their private and public lives.

The Peace Mission went beyond issues of racism and segregation. It endorsed the constitutional amendment that gave women the vote. The Peace Mission itself granted full equality for its female members, liberating them from the confines of marriage and child rearing by insisting on celibate living on Peace Mission properties. In addition, Father Divine sought to challenge the very concept of the nuclear family by having committed members of both sexes put love for and devotion to him as leader above blood and marriage ties, and to communally raise children brought into the group.

Despite his public proclamations of his own celibacy – and discouraging and eventually outlawing marriage among his followers – Father Divine married twice. Throughout his marriage with his first, elderly wife, Penninah, controversy swirled around rumors of the private relations he may have had with several of his young, white and female secretaries. The Peace Mission not only remained intentionally silent about the innuendoes, it defiantly sought to exploit them by openly celebrating Father Divine’s second marriage after Penninah’s death. The Black sexagenarian leader married his white vicenarian secretary, and designated their anniversary as a movement holiday.

Despite his public proclamations of his own celibacy – and discouraging and eventually outlawing marriage among his followers – Father Divine married twice. Throughout his marriage with his first, elderly wife, Penninah, controversy swirled around rumors of the private relations he may have had with several of his young, white and female secretaries. The Peace Mission not only remained intentionally silent about the innuendoes, it defiantly sought to exploit them by openly celebrating Father Divine’s second marriage after Penninah’s death. The Black sexagenarian leader married his white vicenarian secretary, and designated their anniversary as a movement holiday.

In yet another effort to bring social justice to its members, the Peace Mission educated its largely illiterate following so that they could read. It also organized politically against white racist death squad violence. Unfettered by any pretense of mainstream respectability and convinced that they possessed the ultimate social progress template, the Peace Mission openly united with the other radical social justice groups, up to and including the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). In the midst of the depravations of the Great Depression, the Peace Mission sought to display the interracial utopian reality of its social justice model, through its community of farms, homes and cooperatives in upstate rural New York State which it called the Promised Land.[22]

Taking a cue from the Peace Mission Movement, Jim Jones sought to transform his fledging Peoples Temple Christian Church into an entity that would mimic and eventually merge with Father Divine’s social justice utopia. Jones’ goal was to eventually have his own vision of that subversive and non-conformist utopia to occupy the space on the margins of civil and religious culture that Father Divine had created.[23]

During the period of the Civil Rights Movement, when Black people were being brutalized by police and terrorized by KKK racial violence as a backlash to their efforts to integrate the major cities across the South, Jones plotted his takeover of the Peace Mission. While ostensibly pastoring a liberal Pentecostal church, Jones convinced his followers that he possessed the ultimate social progress template, and required that they both adopt his political positions on local and international affairs, and educate themselves on socialism and communism. In addition Peoples Temple fully endorsed gender equality and promoted female leadership inside the group at a time when the mainstream women’s liberation movement was in full swing.

Despite these efforts to promote racial and gender equality, Jones’ personal behavior mirrored the hypocrisy of Father Divine. Even as he proclaimed his fidelity to his wife, Marceline, known as Mother Jones inside Peoples Temple, he was known to have had both short and long term sexual relationships with women in his leadership group. Marriages and family life were permitted among the membership at large, but – as in the Peace Mission – celibacy was upheld as the best practice among the most devoted. Also as in the Peace Mission, Peoples Temple ultimately challenged the very concept of the nuclear family by having committed followers of both sexes put love for and devotion to Jim Jones as leader above blood and marriage ties and by having children brought into the group raised communally.

In a final comparison to the Father Divine movement, Peoples Temple responded to the conservative ascendancy following the radical 1960s by creating, separating, and living out its commitment to its own social justice model through its agricultural project in Guyana. Now known infamously throughout the world as Jonestown, it was presented to the Temple membership as “the Promised Land,” and thousands of people wanted to go.[24]

Social Justice Aftermath and the Legacy of the Final Mass Die-in[25]

Forty years after the mass murder/suicides at Jonestown, Peoples Temple is no more. The Peace Mission still exists, but both Father Divine and his widow and successor, Edna Rose Baker, are dead, and the group itself has long since ceased being a movement; rather, it has atrophied and gradually drifted into becoming a museum and library dedicated to keeping the artifacts around the ministry of Father Divine before an ever-dwindling number of the historically inquisitive and the narrowly curious.[26] Maybe a prophet after all, Jim Jones – possibly anticipating his ignoble end – decided that the collective death for the grand Cause by himself and his followers would better underscore and sear the memory of his presence and his social justice movement into the national consciousness. And it was, although it came at the horrific price of images of dead babies in dead mother’s arms face down in the Guyanese mud around vats of poisoned Flavor-Aid.[27]

Similarly, the generations that were born into the postwar period are beginning to leave the world stage. The Cold War is over with the demise, not only of the Soviet Union, but of its underlying principles of Marxism-Leninism, an ideology once seemingly on an unstoppable, triumphant march.[28] The US, initially the beneficiary of the new world order, now struggles to maintain the global perks of hegemony amongst the shifting contours of international economies and political alliances. Even within its borders, the American population of European descent represent a much smaller majority at the beginning of the 21st century than it had been throughout the 20th, and estimates are that America will become a majority minority country by the mid-21st century.[29]

These changing demographics – responsible in part for the election of the nation’s first mixed race President, Barack Obama – have intensified the struggle for social justice. While social and politically-liberal organizations – including religious groups – have joined with the legacy civil rights organizations to bolster the mainstream demands for social justice, several other groups have arisen in the early 21st century to fill the cutting-edge space once occupied by the Peace Mission and Peoples Temple in the mid-20th century.[30] Jettisoning the centralized and formal church hierarchy organizational motif so central to both the Peace Mission and Peoples Temple, groups like Occupy, BlackLives Matter and the Movement for Black Lives have sprung up across the United States, many of them adopting a strategy of decentralization and “leaderless” organizing instead of the single strong leader model exemplified by, among others, the Peace Mission and Peoples Temple.[31]

Also unlike the Peace Mission and Peoples Temple, these social activist groups are composed largely of individuals who lead separate and autonomous lives and who are linked to the activist groups only through specific organized responses or reactions to incidents of perceived injustice or threat. Occupy, Black Lives Matter and other groups are simply individual activist conduits to work with others on issues of concern. Many of those concerns for economic justice, social security and universal brotherhood, and against systematic racism and racial violence are the same concerns that animated and motivated George Baker Jr. and James Warren Jones 60 to 100 years ago.

But they aren’t completely different. Black Lives Matter and the Movement for Black Lives, like the Peace Mission and Peoples Temple before them, the vast majority of the members are African American. Also like the Peace Mission and Peoples Temple, Black Lives Matter and the Movement for Black Lives welcome input and participation from highly-motivated and empathetic white members who share the groups’ racial angst and interests in the struggle for social justice.[32]

Conclusion: to live and die for the Cause of radical Social Justice

The fundamental difference between current social justice activist groups, and the Peace Mission and Peoples Temple from the last century, remains the depth of commitment required by its leaders and accepted – more accurately, embraced – by the groups’ respective members. Father Divine and Jim Jones responded to the injustices and concerns of their day by organizing specialized high intensity and totalistic radical social groups in the form of Christian churches, and used them to organize utopian intentional communities in which to transform their followers into soldiers, fellow social justice warriors, who would live and fight for the Cause up to and including death and beyond.[33]

Father Divine presided over a protracted group suicide, wherein the participants willingly endured a form of joyful living death, causing them to be so enraptured by the Cause for racial, social and economic justice, which they believed Father Divine embodied, that the most dedicated of them denied or ignored blood and married relations as well as time and space, living in an eternal “now” with no recognition of the time before they came to “know Father,” living as righteous celibates without descendants, or if having them, denying that they did. Living a life focused on “Father,” the faithful were certain to live forever in their physical bodies in the various communal properties of the Peace Mission Movement until in reality they simply grew too old and died, their bodies removed without fanfare or mention, and memories of and references to them were quickly and quietly forgotten.[34]

While sharing Father Divine’s worldview and ultimate goals, Jim Jones was critical of the Peace Mission’s “living death” model. His Peoples Temple followed the teachings articulated by the Peace Mission, that life in the body could be prolonged indefinitely and death was reversible, but Jones also taught that physical death was ultimately inevitable, and that both life and death should be used to proactively advance the cause of social justice. Ultimately Jones demonstrated his commitment to that Cause by presiding over an ecstatic ritual of actual, immediate suicide, which he labeled “revolutionary suicide.” He had not succeeded in converting the world to his cause, but he could – and did – seek to disrupt and ultimately reverse its downward trajectory by the impact of their collective final action. So blinded by certainty in this belief, his dedicated followers participated in that last rite, to “step over” to the other side, certain that to obey the leader unto death was to live forever in the consciousness of those who would in future times continue the fight for “righteousness” or – as Peoples Temple called it – “Divine Socialism.”[35]

Perhaps by setting such stark examples of fanaticism, the social justice warriors of the Peace Mission and Peoples Temple absolved the activists of this century from having to emulate their example. Today’s social justice warrior doesn’t have to commit to a life of “happy” living death or to a “mass suicide die-in for the cause”: they’ve already been done. The only die-ins that the partisans of Occupy, Black Lives Matter and other activists engage in are acts of political theatre. In the shadow of the Peace Mission and Peoples Temple it appears, that the activists in today’s struggles don’t see any efficacy in organizing themselves into totalistic radical social groups that demand that they submit their individual wills to one all-knowing “Father,” especially one who demands celibacy, withdrawal from the world, and possible murder and suicide for the cause. They see no need to repeat the extreme examples of either the Peace Mission or Peoples Temple to be seen as relevant, impactful or successful as dedicated activists to the cause of social justice. If this assessment is correct, it is perhaps in itself Father Divine’s and Jim Jones’ best and hopefully enduring legacy 40 years after Jonestown.

At Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple

Catherine B. Abbott, Jonestown and the Ku Klux Klan: Race in Indiana and Its Influence on Jim Jones and Peoples Temple (2014)

Catherine B. Abbott, Racial Thinking and Peoples Temple (2016)

E. Black, The Three Virtual Intentional Communities of God In A Body In Real Time (1868-2008) (2008)

E. Black, The Reincarnations of God: George Baker Jr. and Jim Jones as Fathers Divine (2009)

E. Black, Laying the Body Down: Total Commitment and Sacrifice to the Cause in the Peace Mission and Peoples Temple (2012)

E. Black, Utopian Justice, Righteousness and Divine Socialism: the Politics of Father Jehovia, Father Divine and Jim Jones and of the Cause They Headed (2014)

E. Black, Casting off the Material Body (2017)

John Collins, Jim Jones and the Malachi 4 Prophecy of Elijah (2017)

Kellen Datta, The Effects of Segregation and Racism in 20th Century America on the Growth of Peoples Temple (2014)

How many people belonged to Peoples Temple?

Robert B. Moore, Jonestown: Catalyst for Social Change (1988)

Nicholas Mullins, The Black Preacher From Indiana: The Reverend Jim Jones and the Rise and Fall of Peoples Temple (2017)

At Father Divine International Peace Mission Movement website

“All the World Rejoices in the Marriage Feast Of the Lamb and the Bride.”

FATHER DIVINE’S Sacrifice on September 10, 1965

FATHER’s Message on the Spiritual Necessity of Abolishing Barriers to Immigration

One of the Largest Demonstrations Ever Staged on the Atlantic Seaboard

At Wikipedia

Black Lives Matter

Die-in

Edna Rose Ritchings

Father Divine

Jonestown

Ku Klux Klan

Latter Rain Movement

Leaderless Resistance

Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness

List of Social Justice Movements

Movement for Black Lives

Reconstruction

Social Justice

Social Justice Warrior

Social Movement

William Branham

Articles

The African American Odyssey: A Quest for Full Citizenship: Reconstruction and Its Aftermath.

Reniqua Allen, Our 21st-century segregation: we’re still divided by race, The Guardian, April 3, 2013.

America’s Reconstruction: People and Politics after the Civil War.

Maurice Brinton, Suicide for socialism?

Communist and Post-Communist Parties of Western Europe.

5 Social Movements That Have Galvanized in the Age of Trump, telesurtv.net, January 12, 2017.

Evan Horowitz, When will minorities be the majority?, Boston Globe, February 26, 2016.

International Peace Mission Movement and Father Divine, by Leonard Norman Primiano, Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia.

Jay Kaspian Kang, Our Demand Is Simple: Stop Killing Us, The New York Times Magazine, May 4, 2015.

Mother Divine, leader of the International Peace Mission, dies at 92, The Philadelphia Inquirer/Daily News, March 6, 2017.

Rebecca Ruiz, Trump’s America will also be a new golden age of activism, Mashable.com, November 15, 2016.

Kris Seavers, “How ‘social justice warrior’ went from hero to joke,” The Daily Dot, October 1, 2017.

“Social Justice and Race Across the Americas in the 21st Century.” https://hemisphericinstitute.org/en/enc09-work-groups/item/349-09-social-justice-and-race-across-the-americas-in-the-21st-century.html. (Editor’s note: This URL is now defunct.)

Matthew A. Spears,“Why ‘social justice warriors’ are the true defenders of free speech and open debate,” The Washington Post, January 9, 2018.

Citations

Immigration to the United States – American Memory Timeline…

U.S. Immigration before 1965 – Facts & Summary – HISTORY.com

Books

Chidester, David. Salvation and Suicide: An Interpretation of Jim Jones, the Peoples Temple and Jonestown. Bloomington and Indianapolis: University of Indiana Press, 1988. Revised ed. titled Salvation and Suicide: Jim Jones, the Peoples Temple and Jonestown, 2003.

Collins, John Andrew, Jim Jones – The Malachi 4 Elijah Prophecy. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. June 15, 2017.

Divine, Mother. The Peace Mission Movement. New York: Anno Domini Father Divine Publications, 1982.

Guinn, Jeff, The Road to Jonestown (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017)

Hall, John R. Gone From the Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural History, New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers, 1987; reprint 2004.

Harris, Sara. Father Divine: Holy Husband. New York: Doubleday Publishing Company, 1953.

Mabee, Carleton. Promised Land: Father Divine’s Interracial Communities in Ulster County, New York. Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press, 2008.

Miller, Timothy. America’s Alternative Religions. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1995.

Moore, Rebecca, Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2018.

Moore, Rebecca, et. al (eds.), Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2004)

Nordhoff, Charles. The Communistic Societies in the United States: From Personal Visit and Observation. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2012.

Reiterman, Tim, with John Jacobs. Raven: The Untold Story of the Rev. Jim Jones and His People. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1982.

Schaefer, Richard T., and William W. Zellner, Extraordinary Groups: An Examination of Unconventional Lifestyles (Waveland Press, Incorporated, 2015)

Watts, Jill. God, Harlem, U.S.A.: The Father Divine Story. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1995.

Weisbrot, Robert. Father Divine and The Struggle For Racial Equality. Boston: Beacon Press, 1984.

Weisenfeld, Judith, New World A-Coming: Black Religion and Racial Identity during the Great Migration (New York: NYU Press, 2017).

You Tube

[1] This article is written on the tenth year anniversary of the author’s first work, The Three Virtual Intentional Communities Of God In A Body In Real Time (1868-2008). Articles by E. Black are designed to examine the heterodoxy of the Peace Mission and Peoples Temple as radical social change entities specific to the internal dynamics of the America’s social, political and cultural periphery as related to the overall 20th century.

The Peace Mission and Peoples Temple were narrowly focused on strategies to realize the self-declared mission, or cause, of their respective leaders. That mission was the realization of universal brotherhood and the fulfillment of the U.S. Declaration of Independence’sproclamation of inalienable rights and guarantees of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness in their immediate lifetimes. In this quest, both groups employed an array of tactics that included interactions with and against various groups ranging from the far left to the reactionary right. The above is important to grasp when discussing the sometimes-seemingly contradictory politics and practices employed by both groups, internally and externally, to promote and achieve their ultimate goals of racial and social justice.

[2] See Social Movement.

[3] See Social Justice and List of Social Justice Movements

[4] See Rebecca Ruiz, Trump’s America will also be a new golden age of activism, Mashable.com, November 15, 2016; and 5 Social Movements That Have Galvanized in the Age of Trump, telesurtv.net, January 12, 2017.

[6] See Edna Rose Ritchings and Father Divine. See also Mother Divine, leader of the International Peace Mission, dies at 92, The Philadelphia Inquirer/Daily News, March 6, 2017.

[7] For the International Peace Mission as a radical social activist group, see International Peace Mission Movement and Father Divine, by Leonard Norman Primiano, Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia; and Mother Divine, The Peace Mission Movement (New York: Anno Domini Father Divine Publications, 1982). For Peoples Temple as a radical social activist group, see Communism, Marxism, and Socialism: Radical Politics and Jim Jones, by Catherine Abbott. For a comparison of the International Peace Mission of Father Divine and Peoples Temple as activist groups on a radical social justice continuum, see Utopian Justice, Righteousness and Divine Socialism: The Politics of Father Jehovia, Father Divine and Jim Jones and of the Cause They Headed, by E. Black.

Peoples Temple and the Peace Mission were organizational vehicles for and expressions of the ministries of their founders, James Jones (1931-1978) and George Baker Jr. (1876- 1965). Although both groups were outwardly organized as Christian churches, their self-understanding was that they were spiritual and/or radical organizations of peoples democracy.

In the popular media of their respective heydays, Peoples Temple and the Peace Mission were known more as political groups masquerading as churches, whose focus was more on upholding and exemplifying the brotherhood of man rather than on the usual displays of worship to the traditional triune deity of normative Christianity. Both organizations were peopled with highly partisan and dedicated individuals, racial and social justice activists, who agreed with the utopian vision of the groups and wished to manifest the tenets of the leader and the group in their lives.

The Peace Mission was at its peak during the decade of the US Great Depression and the recession that preceded World War II. In this era of legalized Jim Crow, this African American named George Baker, Jr., also known as Father Divine, founded an interracially-led organization that presented itself, in the façade of religion, as an institution with focus on justice for and the empowering of the African American urban community of Harlem in New York City, and on serving the needs of its poor with affordable food, clothing, shelter, and employment.

Peoples Temple was at its peak during the 1970s, an era that saw the end of the Vietnam War, the aftermath of the high-level political assassinations of the 1960s, and the ongoing operation of COINTELPRO against the Black Liberation movement. Also using the façade of religion, Peoples Temple presented itself and functioned as an interracial organization whose focus was justice for and empowering of the African American urban communities of California’s two major urban areas, San Francisco and Los Angeles, and serving the needs of its poor with affordable food, clothing, shelter, and employment.

In addition to sharing their central concerns of interracial harmony the Peace Mission and Peoples Temple focused on political aspirations. The political aim of the Peace Mission was called true Americanism; for Peoples Temple, it was called Divine Socialism. For an examination of this dynamic, see Utopian Justice, by E. Black.

Father Divine and Reverend Jim Jones first met in the 1950s and maintained contact until Divine’s death in 1965. Father Divine and his Peace Mission were senior in relation to Jim Jones and Peoples Temple, but the two leaders influenced each other. Their personal, generational as well as their ethnic differences informed how both acted on a shared set of interpretations of and conclusions about issues of social justice as well as the radical and innovative methodologies both employed to address them. Jones took much from the Peace Mission, including organizational structure, nomenclature, philosophy and practice all while reshaping them in ways that his Peoples Temple manifested as markers of its own distinct expression.

[8] For Father Divine as a social justice warrior and tactician, see Robert Weisbrot, Father Divine and The Struggle For Racial Equality (Boston: Beacon Press, 1984), and “Father Divine” in Judith Weisenfeld, New World A-Coming: Black Religion and Racial Identity during the Great Migration (New York: NYU Press, 2017).

For Jim Jones as a social justice warrior and tactician, see Jeff Guinn, The Road to Jonestown (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017), pp. 59-103 and Tim Reiterman with John Jacobs, Raven: The Untold Story of the Rev. Jim Jones and His People (New York: Dutton, 1982), pp. 9-90. For a comparison of Father Divine and Jim Jones in their roles as social justice activist, see The Reincarnations Of God: George Baker Jr. and Jim Jones as Fathers Divine, by E. Black.

[9] For more on the use of the term “Social Justice Warrior” and its applications, see Matthew A. Spears, “Why ‘social justice warriors’ are the true defenders of free speech and open debate,” The Washington Post, January 9, 2018; and “How ‘social justice warrior’ went from hero to joke,” by Kris Seavers, The Daily Dot, October 1, 2017; and Social Justice Warrior.

[10] See Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness.

[11] For more on the intertwined history of social progressivism and the development of the United States, see A History of Social Movements in the U.S.: A collection of links and resources relating to the history of social justice movements in the United States, Thoughtco.com; and Social Movements and Progressivism, Center for American Progress, Americanprogress.org, April 14, 2010.

[12] Although a detailed examination of the post-Civil War Reconstruction period (1865 – 1877) and its aftermath in US history is paramount to fully grasping the social, political and cultural context in which both the Peace Mission and then Peoples Temple arose, the scope of that task is beyond the confines of this paper.

Nonetheless, it is our studied conclusion that it was the socially progressive hopes of national reconciliation as well as the racial disappointments, tragedies and contradictions of Reconstruction and its aftermath – particularly as experienced by individuals who lived through the postwar period following each World War of the last century – that Father Divine and Jim Jones tried to address. For more, see Reconstruction Era.

[13] For more on the social, political, cultural and historical backlash to the Reconstruction period, see Ku Klux Klan; Jim Crow; America’s Reconstruction: People and Politics after the Civil War; and The African American Odyssey: A Quest for Full Citizenship: Reconstruction and Its Aftermath.

[14] On 19th-century Communist societies in the US, see Charles Nordhoff, The Communistic Societies of the United States (New York: Hillary House, 1875).

On European immigration to the US between 1880 and 1920, see U.S. Immigration before 1965 – Facts & Summary – HISTORY.com: “In that decade [1890s] alone, some 600,000 Italians migrated to America, and by1920, more than 4 million had entered the United States. Jews from Eastern Europe fleeing religious persecution also arrived in large numbers; over 2 million entered the United States between 1880 and 1920.”

See also: Immigration to the United States – American Memory Timeline…: “In the late 1800s, people in many parts of the world decided to leave their homes and immigrate to the United States. Fleeing crop failure, land and job shortages, rising taxes, and famine, many came to the U. S. because it was perceived as the land of economic opportunity.”

[15] Father Divine denied being “mortal” and eschewed any and all attempts at providing a biography before his public ministry became known in the 1930s. Although he died in 1965, his successor Mother Divine continued to follow his wishes in this regard, as do his few remaining followers.

Divine’s biographer, Jill Watts, has established to our satisfaction a reliable biography in her book, God, Harlem U.S.A.: The Father Divine Story (Berkeley, University of California Press, 1995). Ironically one of the reasons that George Baker Jr. in his assumed role as Father Divine, “God” may have not wanted to reveal his identity was to conceal his past as a follower and disciple of Samuel Morris, who founded and led a small heterodox New Thought class that met in the home of a female evangelist named Harriet Snowden in Baltimore, Maryland at the beginning of the 20th century. Under the name Father Jehovia, Morris was accepted as “God” by Baker and the class. For his faithfulness, Father Jehovia designated the young George Baker Jr. as his Messenger and as “God in the sonship degree,” i. e. Morris’ second in command.

[16] For an excellent biography that underscores and fleshes out the above sketchy biography of George Baker Jr. in his assumed role as Father Divine, “God,” of his own interracial, intentional social justice community, as well as a more in-depth examination of his principal followers and the contradictory impact and legacy of the Divine Movement on matters of race, sex and gender in the decade before Divine’s death, see Sara Harris, Father Divine, holy husband (New York: Doubleday Publishing Company, 1953).

[17] Biographical information on the young James Warren Jones was taken primarily from Guinn, The Road to Jonestown and Reiterman, Raven. Rounding out the early biographical narrative with emphasize on the founding of Peoples Temple and its immediate antecedents context taken from chapter 1, “Beyond White Trash” in Rebecca Moore, Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2018).

In addition, the book, Jim Jones – The Malachi 4 Elijah Prophecy, by John Andrew Collins (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (June 15, 2017) pioneers a deeper understanding of the young and newly Reverend Jim Jones and his relationship to the postwar Latter Rain movement and one of its principal leaders, Reverend William Branham. This is significant as the Latter Rain movement, conceived at the beginning of the Cold War, was patriotic and politically right wing, with some Latter Rain activists and ministers directly tied into the second resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan.

The irony is that Jim Jones was a secret admirer of the communist cause, posing as a charismatic Pentecostal minister who used the Latter Rain movement and Rev. Branham to gather the initial core of his members in what would become the virulently anti-Klan, interracial and pro-socialist Peoples Temple. It is nevertheless right in line with what we have learned of the contrarian audaciousness of Jim Jones.

Although more on this angle is outside of the scope of this paper, we encourage readers to read more on the Latter Rain Movement and on Reverend Branham.

See also, John Collins, Jim Jones and the Malachi 4 Prophecy of Elijah.

[18] The summation of Jim Jones and Peoples Temple is gleaned principally from Moore, Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple; and David Chidester, Salvation and Suicide: An Interpretation of Jim Jones, the Peoples Temple and Jonestown (Bloomington and Indianapolis: University of Indiana Press, 1988).

Jim Jones and his wife – and later, Peoples Temple itself – were pioneers of trans-racial adoptions. Jim Jones promoted his “rainbow family” as a living “sample and example” of his teachings and commitment to “the cause” of radical, racial social justice. His seven children were Agnes Paulette Jones (white); Stephanie Jones (Asian); Suzanne Jones Cartmell (Asian); Lew Eric Jones (Asian); Stephan Gandhi Jones (birth son); James Warren Jones, Jr. (black); Jim Jon Prokes (birth son). He is also alleged to have fathered John Victor Stoen (white).

[19] Grandparent organizations in a sociological, not in a literal or programmatic sense.

[20] Neither the Peace Mission nor Peoples Temple demonstratively became “majoritarian movements,” notwithstanding Peace Mission propaganda of the 1930s to the contrary. Actual discipleship in either group required time and total commitment to the Cause, as defined by the dictates of the leader, and although both groups had a flare for the melodramatic and the novel in turns of outreach, and although both could – and did – attract crowds in their thousands for certain well-advertised events, core membership in both groups overall remained comparatively small. For our discussion on Peace Mission peak numbers see note 32 at Casting off the Material Body. For a discussion on how many people joined Peoples Temple, see How many people belonged to Peoples Temple?

Despite this fact, neither leader considered themselves or their groups either peripheral or marginal. To the contrary they viewed their activities as manifestations of “universal mind and will” on the “earth plane” and were overall disdainful of other religious and/or social active groups that vied for the same audience, regardless of how large, influential or established. Jim Jones is recorded at Tape Q 1059-1 as declaring that, “I am creator of … the Peace Mission, I am the creator of that.” And “There wasn’t any God till I came along. There was nobody to help the people. Your God of religions and Bibles– the babies are going to bed hungry, black people have been treated like dogs just because of the color of their skin, Jews were murdered, and they were supposed to be the chosen people of the so-called Sky god, there was no Sky god, and I’m an earth God, though, child, and I’m very much alive.” Father Divine is quoted in Weisbrot (page 33) as saying that “Because your God would not feed the people, I came and I am feeding them… That’s why I came, because I did not believe in your God.”

[21] Establishing their respective “Promised Lands” – self-governing intentional communities for life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness for their followers – was the central concern and focus of both groups. Father Divine announced that it was his intention to found a Divine City. The Peace Mission set up its Promised Land properties in Ulster County, New York State in the 1930s. Peoples Temple made an attempt to establish a community in Redwood Valley, California in the 1960s, but found more success when it established an agricultural project in the jungles of Guyana, South America – later known as Jonestown – in the mid-1970s. Neither Promised Lands survived their founding group, and both are now defunct.

[22] This summarized overview of the heterodox social justice practice of the Peace Mission relies heavily on the accounts of the Peace Mission as an organization in Carleton Mabee, Promised Land: Father Divine’s Interracial Communities in Ulster County, New York (Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press, 2008); “The Father Divine Movement” in Richard T. Schaefer and William W. Zellner, Extraordinary Groups: An Examination of Unconventional Lifestyles (Waveland Press, Incorporated, 2015); and Mother Divine. For a contemporary account of a Peace Mission mass demonstration for social justice, see One of the Largest Demonstrations Ever Staged on the Atlantic Seaboard, October 1, 1935.

In the face of the scandal surrounding his intergenerational and interracial (and allegedly celibate) wedding to his young white secretary in 1946, Father Divine proclaimed an annual “international, interracial, universal holiday” to celebrate and commemorate it as a way to underscore the Peace Mission Movement’s commitment to the cause of radical social justice. See, All the World Rejoices in the Marriage Feast Of the Lamb and the Bride. See also FDIPMM.

[23] For more on Peoples Temple as a self-conscious social justice competitor of, and self-proposed successor organization to the Peace Mission see “Part V African-American Freedom Movements “; “Father Divine’s Peace Mission Movement”; and “Peoples Temple” in Timothy Miller (ed.), America’s Alternative Religions; and “Jim Jones of Peoples Temple. Guyana” in Mother Divine; and “The Problem of Succession and Survival” and “Jim Jones Adopts Divine’s Promised Land as a Model” in Mabee; and “Daddy Jones and Father Divine: The Cult as Political Religion” by C. Eric Lincoln in Rebecca Moore, et. al (eds.), Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2004); and E. Black, Three Virtual Intentional Communities.

[24] Peoples Temple summation from Moore, Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple; Guinn; Reiterman,and John R. Hall, Gone From The Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural History(New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers, 1987).

[25] See Die-in as a form of political theatre and protest performed by social justice groups and activist.

In his role as Father Divine “God in a body,” George Baker Jr. as an individual was supposedly immortal. He died September 10, 1965. When publicly questioned about the apparent contradiction, Mother Divine said that Father Divine had quoted the words of Jesus: “no man has power to take my Life; but I lay It down” (John 10:18). Thus the death of God (Father Divine) at the age of 86 was interpreted as a “laying down of the body,” a willful sacrifice. Mother Divine went on to say that “God taking on the body of Father Divine” in the first place was itself an act of sacrifice so that “laying that body down” was just another degree of sacrifice that “proved” that Father Divine was God and thus eternally present with or without a body. From the Peace Mission perspective, God becoming Father Divine – and the death of Father Divine – could be seen as forms of an individual “die-in” against the ignorance of mortality and for the cause of redeeming human beings to “righteousness.” See Mother Divine’s comments, FATHER DIVINE’S Sacrifice on September 10, 1965.

The final protest by Peoples Temple was an actual, not acted, mass die-in at Jonestown, ordered by Jim Jones and facilitated by his inner leadership circle. This final die-in had been preceded by months of periodic drills called “White Nights,” in which the Jonestown collective in the Peoples Assembly discussed sacrificing the entire community in mass death for the cause. This gathering was Peoples Temple form of “radical mass democracy.” For extended commentary of the final day and of the tape recording that captured the conversation, see The “Death Tape.” For a through examination of the concepts mentioned above in regards to both groups, see note 19 at E. Black, Laying the Body Down: Total Commitment and Sacrifice to the Cause in the Peace Mission and Peoples Temple.

[26] For more on the status of the Peace Mission following the death of Mother Divine, see Dedication of FATHER DIVINE’s Library & Museum.

[28] For a commentary on post-1991 Marxism-Leninism in the West, see Communist and Post-Communist Parties of Western Europe.

[29] For more on the demographic projections for the US in the 21st century USA, see Evan Horowitz, When will minorities be the majority?, Boston Globe, February 26, 2016.

[30] For an examination on the continuing activism around the issues of racial social justice in the US in the 21st century, see Jay Kaspian Kang, Our Demand Is Simple: Stop Killing Us, The New York Times Magazine, May 4, 2015; Reniqua Allen, Our 21st-century segregation: we’re still divided by race, The Guardian, April 3, 2013.

[31] For more on the leaderless model of organizing adopted by many social justice activist groups in the US in the 21st century see Leaderless Resistance.

[32] See, Black Lives Matter and The Movement for Black Lives.

[33] While the Jonestown faithful’s fanatical commitment to the cause of Peoples Temple on November 18, 1978 is well known, lesser known and discussed is the Peace Mission equally fanatical steadfastness up to death for the cause. On the resiliency of the few remaining aged members of the Peace Mission, it has been written that: “The Peace Mission’s core beliefs will not allow its followers – no matter how few in number – to concede defeat.” Even in the aftermath of Mother Divine’s death and her non-designation of a successor for them, they “trust in Father’s spirit,” as they have “always done.” Audrey Whelan, Mother Divine, leader of the International Peace Movement, died at 92, philly.com, March 6, 2017.

[34] We thoroughly examined Peace Mission life as a form of joyful living death at the heading “No Sex = Eternal Life” at Casting off the Material Body.

[35] For a left/libertarian summation, see Maurice Brinton, Suicide for socialism?

(E. Black is a regular contributor to this site. Her full collection of articles may be found here.)