(Editor’s note: A timeline of the 1978 Guyana Inquest that accompanies this article may be found here.

(Aliah Mohmand is a student with an interest in Peoples Temple. Her research has resulted in multiple projects regarding the aftermath of the Jonestown tragedy. Aliah attends Kalamazoo College, pursuing studies in History and Finance. Her other articles in this edition of the jonestown report are The Reporting of Mohamed Hamaludin, and What More Is Left to Learn? A Review of Cult Massacre. Her full collection of articles for this site may be found here. She may be reached at aliahmohmand@gmail.com.)

Over the past four decades, thousands of primary source materials, survivor testimonies, and knowledge relating to Peoples Temple and Jonestown have emerged. Nevertheless, the narratives of the deaths at Jonestown on November 18, 1978 remain convoluted. Countless myths and inaccuracies about the tragedy persist to this day. Survivor testimonies in particular tend to be most affected.

As investigations into Jonestown continue, it is more important than ever that we rely on early sources rather than secondary materials. Studies have shown that memory is highly susceptible to changes and that details can be altered over time – especially when recollected many, many times.[1] These accounts, altered by changing memories – however unintentional those changes may be – create a grave challenge to researchers.

Arguably, then, one of the most important collections of survivor testimonies comes from the December 1978 Guyanese government’s inquest into the mass deaths at Jonestown. The inquest, for which a transcript is available, produced a written record of the testimonies of numerous Jonestown survivors and Guyanese authorities. Yet despite its importance, the inquest poses the greater question: can it be completely relied upon?

*****

The Guyanese government was thrown into chaos as the news of the deaths in Jonestown became known. Conflict and debate persisted between the Guyanese government and the American State Department to determine whose responsibility it was to handle this unprecedented tragedy. Jurisdiction would not be so clear.

In the first hours following the mass deaths, local Amerindians reportedly rushed into Jonestown in search of valuable loot, and in the process, compromised much of the evidence of the crime scene.[2] The arrival of the Guyanese Defense Forces (GDF) on the morning of November 19 added to the destruction. Finally, an early pathological investigation led by Guyanese Chief Bacteriologist, Dr. Leslie Mootoo, on late Monday, November 20 and Tuesday, November 21, produced inconsistent conclusions. These events in the immediate aftermath would hinder the effectiveness of later investigations.

The Guyanese government and the American State Department had initially called for an unspecified number of “spot autopsies”[3] and a thorough pathological investigation into the deaths. This plan quickly proved too ambitious for the burdened nation. In the following days, Guyanese leaders realized the complicated logistics behind an on-site burial or by having relatives come identify the victims. Instead, the Guyanese government and an American Task Force decided to repatriate bodies to the U.S. as soon as they did to begin the process of identification.[4] In that way, Guyana could limit its responsibilities and protect its international reputation. However, despite its otherwise haphazard approach to the tragedy, the government did require one specific investigation into the mass deaths: the coroner’s inquest, later known as the “Guyana Inquest.”[5]

*****

As the true extent of the Jonestown deaths unfolded, everyone on the scene – the national government, the American Embassy, and the U.S. military task force charged with removal of the bodies – recognized the need to waive many of the protocols usually followed in the deaths of Americans overseas. One was the requirement to autopsy the remains: Guyana lacked the resources, and perhaps even the ability, to carry out nine hundred autopsies prior to the issuance of death certificates. The coroner’s inquest stood as one of the rare exceptions.[6]

The Guyanese Coroners Act of 1887, an act predating Guyana’s decolonization, requires that “where an unnatural death is reported to or comes to the knowledge of the coroner, he shall … if necessary, hold an inquest…” In accordance with the act, Haroon Bacchus, one of Guyana’s chief magistrates, was charged with the responsibility to proceed with the inquest in the North West District where Jonestown was located. Emanuel “Mannie” Ramao, Guyana’s director of public prosecutions, was selected as the attending prosecutor.

The State Department’s first reference to the coroner’s inquest[7] came December 12, 1978, nearly a month after the tragedy. The first cables from the Secretary of State to the American Embassy in Georgetown authorized approval for a “consular officer”[8] to testify at the inquest[9] and discussed a New York Times correspondent’s request to be allowed access to the proceedings,[10] which took place at the Matthews Ridge courthouse, approximately 28 miles from Jonestown. The courthouse itself consisted of a small, one-room building reminiscent of a classroom.

Adhering to the provisions for a coroner’s inquest, a modest five-member jury was selected, all from Guyana’s North West District. A San Francisco Examiner reporter detailed some of their profiles:

Charles Hines, a 66-year-old road foreman with a habit of regularly scratching his inner ear with the business end of his ballpoint pen.

Ivelew Orrell [Ivelav Worell], a worker at the Matthews Ridge power station and, at 37, the youngest panelist.

Prince Albert Glasgow, a 53-year-old welder who seems to relish the double takes that follow the announcement of his name. Later he concedes: ‘It’s really my first name. I was the first child and my father wanted to make a big deal out of it.’

Learn Poole, 46, a friendly mother of four.[11]

*****

Over the course of six days, the coroner’s jury heard the testimonies of fourteen individuals, including six from Jonestown survivors. They include:

Odell Rhodes, a 36-year-old teacher and Vietnam veteran who escaped by deceiving a nurse and then hiding behind a cottage.

Stanley Clayton, a 25-year-old cook in Jonestown, who escaped the deaths by running past the guards and into the jungle as the deaths occurred.

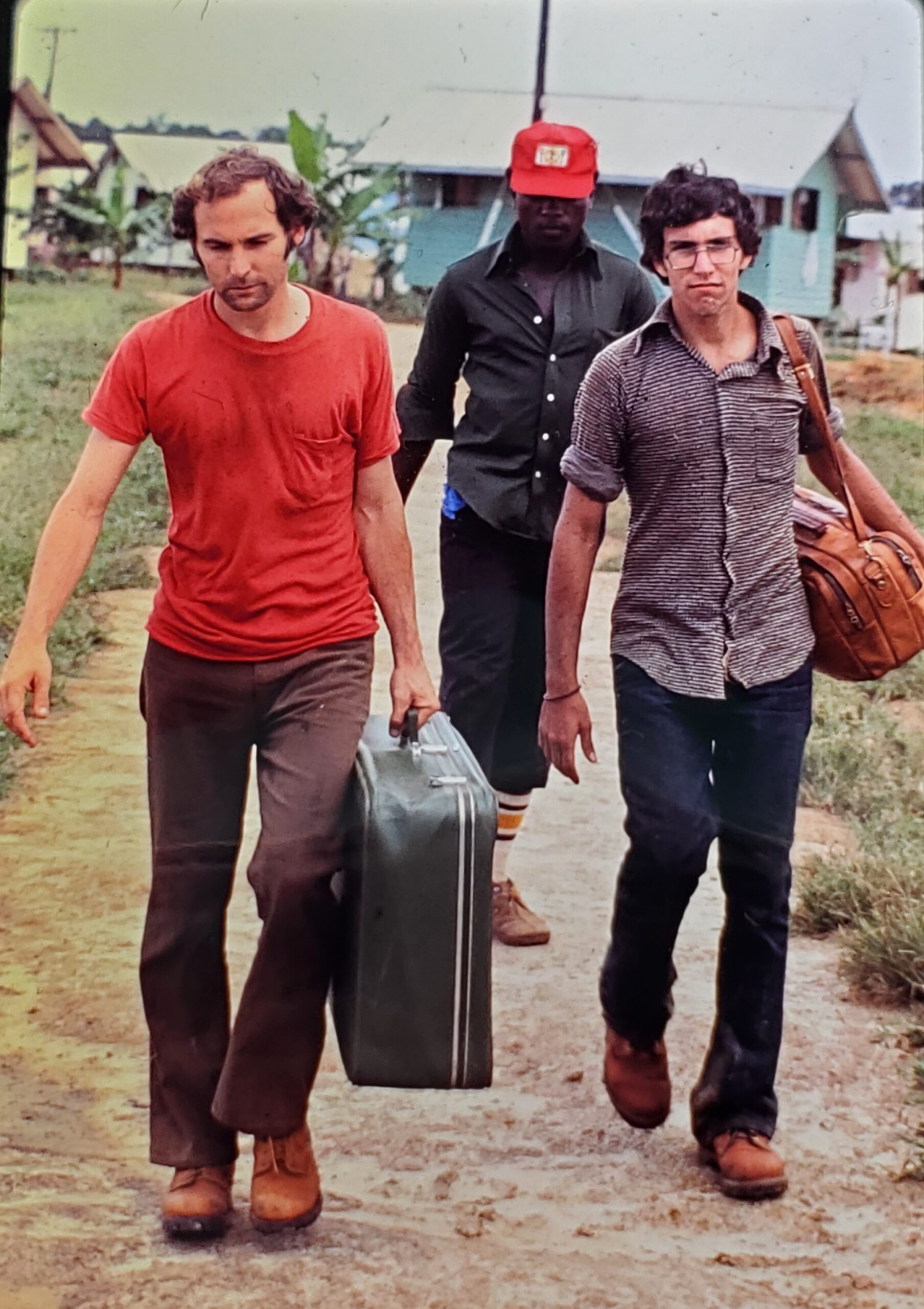

Brothers Tim and Mike Carter, aged 30 and 20, respectively, who were tasked by Jonestown’s leadership to carry money and gold to the Soviet Embassy.

Mike Prokes, a 30-year-old public relations head and former reporter, who accompanied the Carter brothers.

Herbert Newell, a 20-year-old who was manning the Temple’s Cudjoe ship on the Kaituma River as the deaths happened.

Due to the remoteness of Matthews Ridge, the inquest had less international media coverage in contrast to the preliminary trial of Larry Layton, which was occurring at the same time in Georgetown. Nevertheless, a limited number of press correspondents – including reporters from the San Francisco Examiner, the Los Angeles Times, and the New York Times[12] – traveled to Matthews Ridge to attend the proceedings.

*****

The inquest officially commenced on December 13, with three Guyanese witnesses called to the stand: Assistant Police Commissioner for Crime Cecil “Skip” Roberts, Dr. Leslie Mootoo, and Police Photographer Richard Oliver.

Roberts’ testimony, detailed yet succinct, began with his arrival in Jonestown on early Monday morning, November 20, along with Odell Rhodes. Contributing to early news stories and official reports, Roberts said he first estimated the official body count in Jonestown to be “between 400 and 500,” an estimate that turned out to be grossly in error.[13]

On my arrival at Jonestown I saw a large number of dead bodies of human beings in an area close to a large tent. The number of dead bodies I saw looked like between 400 to 500. The area in which bodies were; was one; and after checking bodies individually I counted 914 bodies dead.

Robert’s statement on the details of his time in Jonestown was fixated on the cause of death of Ann Moore, who was found with a gunshot wound on the left side of her head. Located in the same place where Ann died – Jim Jones’ cabin – were 13 more residents, including Maria Katsaris, Karen Layton, and Jim McElvane, all of whom were close associates to Jones. Nine elderly residents were also found in an area away from the pavilion, in two “hospital-like” buildings.

Twenty-two other bodies were found in an area other than the area where the bulk of the bodies were found. Thirteen of the said 33 bodies[14] were found in the house of James Warren Jones, the said home was identified by the said Odell Rhodes. Twelve of these bodies showed signs of consistent with poisoning and one body (i.e.) that of Ann Elisabeth Moore which appeared to have a gun shot wound on the left side of her head. On a bed in the first bedroom a body identified as Maria Katsaris was lying face downwards. … Ann Elisabeth Moore[‘s] body was on the floor; in the said room on another bed was the dead bodies of a young child 7 to 8 years. The child was identified as that of Timothy Jones. … The next bedroom had some dead bodies also the number of which I now remember to be 9. Two of these bodies were given; one, as Karren [Karen] Layton age 19 and Jim McElvain [McElvane].

Roberts also testified that he accompanied the Carter brothers and Mike Prokes to locate the cash they had abandoned on their way out of Jonestown.

In course of further enquiry a sum of money in excess of $550,000 U.S. dollars as well as a large sum of Guyanese dollars were found. These were found in Jonestown. The bulk of this amount was found in a chicken feed bag which was in the feeding room of the chicken farm owned and operated by the said organization. This chicken farm is about two miles away. There is a roadway which leads from the settlement to the chicken farm. Another portion of the money was found buried in a banana grove approximately 600 yards from the main area. Approximate $4,800 (U.S.) was found in the possession of three men namely Michael Prokes, Timothy Carter and Michael Carter. I was taken to both places by Michael Carter. These sums are now in the possession of the police. I also found a quantity of rings, gold and diamond which are also in the possession of the police.

Roberts was one of the first prominent Guyanese officials to be on the scene in Jonestown, and his testimony includes no noticeable contradictions or inaccuracies. But as with all of the witnesses, his testimony is not without its faults. He found himself fascinated by Ann Moore, as she was the only person besides Jim Jones to have died by gunshot. Notably, Roberts was the first to offer the theory that Ann Moore was responsible for the six gunshots heard in Jonestown. He believed that she “shot Jim first, at his bidding, before shooting a dog, then [the chimpanzee] Mr. Muggs – who was shot twice – then another dog, and then, late that night, herself.”[15] Roberts would later contradict himself. Six months later, he suggested to Ann’s sister Rebecca Moore and Fielding McGehee during their May 1979 trip to Guyana that Ann was not likely responsible for all six gunshots heard that night.

[Roberts] now said that Muggs’ owner, Albert Touchette, shot him twice, and that accounted for the first two shots. The third and fourth shots, in quick succession, were for two dogs. The fifth shot was for Jim. Roberts no longer said Annie shot Jim. He felt Jim killed himself, although it was possible that Jim had shot Annie, or that Annie had shot him.[16]

In the moment, however, Roberts conceded in an interview with the San Francisco Examiner that “there were still a lot of things [he] didn’t feel comfortable talking about.”[17] Even one of Guyana’s top investigators, he found himself bewildered by the deaths. In her recollections of meeting with Roberts, Moore theorized that his change in theory “was to accommodate us” or that “perhaps he had received new information. Or perhaps it simply wasn’t that important to him, and he had forgotten.”[18] As with any testimony, it cannot be taken as the absolute truth. Certainly, Roberts’ testimony provided a substantial timeline into the Guyanese government’s response to the mass deaths.

Next to be heard was Guyana’s chief pathologist, Dr. Leslie Mootoo, whose testimony ended up adding confusion and suspicion into the deaths. Specifically, his details concerning the presence of injection marks on bodies and the number of toxicology tests performed have changed several times since his cursory examination of the remains. In contrast to his later statements, as analyzed by Rebecca Moore, Dr. Mootoo’s testimony at the inquest failed to give voice to his belief that residents had been injected, probably against their will, with the poison.[19]

In an interview given to The Chicago Tribune a few days after his inquest statement – as quoted by the New York Times – Dr. Mootoo stated:

“I do not believe there were ever more than 200 persons who died voluntarily.”[20]

Despite his inconsistencies, his credentials as the first medical examiner on scene in Jonestown granted him great credibility among the mainstream press. His statements were often misinterpreted, or at worst, misconstrued, allowing misinformation and rumors to proliferate. The media and its audience sought out sensationalist stories and narratives, and did so at the expense of accuracy. Already convoluted enough, Dr. Mootoo’s account only had the complexity of his testimony exacerbated by the media’s confusion with medical terminology. For example, the same New York Times article reported that Dr. Mootoo “based his conclusions on 70 autopsies performed on victims.” However, Dr. Mootoo said at the inquest that he performed a number of toxicology studies, not autopsies, on the deceased.

I then carried out post mortem toxicology study for poison on several other dead bodies among these that had been identified by the said Odell Rhodes. … I did also a toxicology study for poison on 25 unidentified dead bodies from different parts.

Dr. Mootoo was one of the most prominent voices in insisting that many in Jonestown were injected against their will. His conclusion conflicted dramatically with that of Commissioner Roberts, who told a New York Times reporter that he believed “most of the others ‘killed themselves,’” except for the children and elderly.[21] It is possible that Dr. Mootoo altered his testimony to appeal to such a narrative. Or more simply, perhaps he was inconclusive himself. Dr. Mootoo’s testimonies are best not taken at face value and, as with any account, should be scrutinized critically.

One final testimony on the inquest’s first day. Detective and Police Photographer Richard Oliver offered a brief statement into his role of photographing the aftermath of the deaths on Monday, November 20. Using the identifications made by Odell Rhodes, Oliver specifically focused on photographing the various scenes of the deaths, many of which were exhibited at the inquest.

I took photographs of the body identified to me as James Warren Jones and made prints from negatives, this is the photographs of James Warren Jones tendered, admitted and marked exhibit C1 and C2. I also took a photograph of Ann Elisabeth Moore, this is the said photograph of A.E. Moore tendered, admitted and marked “D”.

Remarkably, despite the value of Oliver’s photographs, very few – if any – of them are known to have surfaced. Although copies of the transcript of the inquest were sent to the FBI to assist with its investigation, there is no indication that any of Oliver’s photographs made their way stateside. The only possibility that any of them survived is that a 32-page Jonestown special of the Guyana Chronicle newspaper featured a page of many unseen photographs from the aftermath. These may have come from Oliver himself.[22]

*****

On the second day of the inquest, the magistrate decided to take a tour of Jonestown in the company of the coroner’s jury and two survivors, Stanley Clayton and Odell Rhodes.

However, for Odell Rhodes, this was not his first time visiting Jonestown after the deaths. On Monday, November 20, two days following the deaths, under the supervision of the GDF and Skip Roberts, Rhodes, Mike Prokes, and the Carter brothers were taken separately back to Jonestown to assist with body identification. The survivors worked for hours under the duress of Guyana’s humidity to identify at least over a hundred bodies.[23] Despite the vigor of their labor – and the inevitable trauma – their efforts were futile. As the evening neared, the U.S. Army announced that they would not be accepting any of the identifications made by the survivors.[24]

The Jonestown site that once thrived with life now sat abandoned, as evidenced by the rotting grilled cheese sandwiches left behind.[25] Although the 900 bodies had been long removed at this point – the topsoil plowed over and gasoline sprinkled – the scents of cyanide and death persisted.[26] The jurors carefully followed the magistrate, who pointed out the “heaps of clothing” and “numberless of black-and-white sneakers”[27] scattered among the muddied paths. Meanwhile, Odell Rhodes and Stanley Clayton served as guides for the delegation. They directed them towards the cottages and answered the jurors’ innumerable questions.

Of most interest to the inquest delegation – and to the press correspondents who also trailed behind – was the discovery of an organizational chart detailing where the “power lay in [Peoples Temple]”[28] and thereby providing insights into Jonestown’s complex hierarchy. The reality is that with the ever-changing and dynamic leadership system built within the Temple, there exists not a single chart to authentically define who was who in Jonestown. Yet there was apparently little time for further probing. After all, the jury had a verdict to deliver.

Both the magistrate and the jurors eventually found themselves increasingly ill by the minute and encouraged the tour to come to an end.[29]

“‘I feel sick,’ said Bacchus, ‘I suggest we move on. I feel quite ill.’”

Finally, after seeing Jonestown for themselves, one of the jurors, Albert Foreman, remarked:

“I am not happy. I am not impressed with this Jonestown at all. … To me it looks like a slave camp.”[30]

In addition to its tour of Jonestown that day, the jury heard the testimony of Odell Rhodes. Contrary to the formality expected of a government-sanctioned inquest, a New York Times reporter described the atmosphere of the inquest as “less formal” than one would rightfully anticipate.[31]

As the first Jonestown resident to testify, Rhodes provided clarity into the conditions in Jonestown. Rhodes noted the punishments that occurred – including his own, after once expressing his desire to leave, as well as that of Thomas Partak, who was severely punished after he had routinely made known a similar wish to return to the U.S.[32]

I once wrote a letter to Jim Jones expressing my desire to leave settlement and I also expressed my said desire in front of a public gathering at the pavilion. I was punished by being put to do longer hours because of desire to leave. There were others who wanted to leave namely: Tom Partak, he was about thirty-five years. As a result he was given physical punishment; he was beaten by the security guards on Jim Jones instructions. He was cuffed about.

Rhodes’ insight stood out in contrast to the many exaggerations and myths of the punishments in Jonestown that had been circulating in the media. His statement – corroborated by the numerous audiotapes that feature the community’s harsh criticisms and beatings – gives a less sensational account of what occurred in Jonestown and, most importantly, why they happened.

Rhodes finished his statement by mentioning prominent events that had happened in Jonestown over the past year, including the community’s “Six-Day Siege” and the petition residents had signed to prevent Congressman Leo Ryan from entering Jonestown.[33]

The only other testimony to be heard that day was that of Seeram Persaud, a Guyanese clerk who had followed the inquest delegation on its tour of Jonestown.

*****

On the following day, December 15, Rhodes continued his testimony and detailed his survival. Like a handful of other survivors, Rhodes’ story received much media attention, as he was one of the few to be in Jonestown as the deaths began. Three years following the inquest, Rhodes’ account, in addition to Stanley Clayton’s, was used extensively in the book Awake in a Nightmare.[34] Other than the book, an interview with the FBI given upon his return to the U.S.,[35] and a brief number of statements he gave to the media in the aftermath, his inquest testimony would be his most elaborate statement ever given. He died in 2014 without giving any other interviews.

Consistent with the testimonies heard from other witnesses, Rhodes described the mass deaths as beginning with the children and their mothers. But his testimony was unique in that he was present as some of them occurred.

Some one had handed to me a small child named Derrick Johnson about ten to eleven years of age and asked me to help him he had collapsed and I noticed his eyes were rolling and he went into convulsion and I put him to lie down outside in the fields. … On this occasion having seen this child dying I realized it was in fact poison which was in the drum. I started picking children up off the ground and putting them down. I was a teacher and I was just trying to comfort them. I spent about fifteen minutes there and then walked about four or five yards away and began contemplating what I should do.

After realizing that Jones’ White Night was the real one, Rhodes deliberated ways to make his escape. He described it this way.

Doctor Shack [Jonestown doctor Larry Schacht] said he needed a stethoscope and I really this message to a nurse name Phyllis Chaiken and she started walking towards the Nurses Office and I walked with her. The nurses office is about one hundred and twenty-five yards from the pavilion … I went to the nurses office for a stethscope [stethoscope] and she went to the Doctor’s Office for stethscope. I went through the back door of the Nurses Office and unto [into] the dwelling quarters of the Senior Citizens. … I then went out the back door of the senior citizen quarters and went and hid under the building. I went into hiding for about thirty minutes, it was just about getting dark.

Rhodes’ inquest testimony seems coherent, but his statement has multiple omissions. For instance, he vividly described in Awake in a Nightmare how he had hugged Marceline Jones while residents took the cyanide punch. There is no such mention of that detail at the inquest. He also stated that while accompanying Chaikin, he was prepared to “hit her, or something worse,”[36] in order to secure his survival. Again, he did not mention this at the inquest.

This is understandable. In his desperate and intense desire for survival, certain details are often – and sometimes unknowingly – omitted or forgotten, depending on the context of the interview. Rhodes later told the author of Awake in a Nightmare he had already spent countless hours “telling and retelling his story”[37] to hordes of officials and authorities. It is plausible to expect that there may be minor discrepancies between statements. When examining a witness’s account across numerous statements, it is imperative to remember that memories are reconstructed, meaning that they are influenced by new information, beliefs, imaginations, stories, etc. – not “played back”[38] from the event. No matter how vivid they may be, recollections are not error-proof. Furthermore, “extreme witness stress”[39] is known to affect the accuracy of memories. The survivors at the inquest had certainly experienced distressing circumstances concerning their fates, even as they received little assistance or guidance from authorities. It was easier for many survivors to speak in greater detail regarding their experiences after returning to the U.S., although such statements are already several steps removed from their initial account of the tragedy.

*****

Unbeknownst to Rhodes during his escape, Stanley Clayton was also making his leave. Shortly after Rhodes finished his testimony, Clayton began his. Clayton’s testimony followed a similar structure to that of Rhodes’, albeit shorter. Similarly, Clayton articulated his dissatisfaction with Jonestown and was also admonished after once telling others that he wanted to leave. As part of Jonestown’s kitchen crew, he was also one of the very few surviving witnesses – if not the only – to watch the early preparation of the mass deaths occur.

Marceline Jones said over the loud speaker after Congressmen left that everything was alright and they should return to their quarters and freshen up and meet again for that evening and discussed the events that occurred that day. About half an hour after this the settlers were summoned to pavilion over the public address system. The kitchen crew does not have to attend meetings. Doctor Shack and Joyce Touchette came into the kitchen and collected a half steel drum and had with them boxes of cool aid and two containers containing brown liquid. I know from this something was going on.

Eventually, though, Lew Jones – one of Jim and Marceline’s adopted children – came to the kitchen to order the crew to the main pavilion. There, Clayton overheard Christine Miller express her dissent over the impending deaths. Afterwards, though,

I saw mothers taking their babies up. I saw a Nurse give a baby a set from a cup and then saw a Nurse injected a baby. After the mothers to their babies and they were injected persons would take the babies out in the fields. I saw every young babies in arms being treated in this way. … Marceline Jones went around embracing people. I heard her saying to one of the persons should see them in the next life.

Whereas Rhodes managed to escape midway through the deaths, Stanley Clayton remained present until a small number of Jonestown residents – between 100 and 200 – remained. After hearing a report over the PA system for all “persons with weapons were to report to the radio room,” Clayton started small talk with the guards.

I then went around to all the security men saying that I was getting ready to go. I reached Ray Jones and told him I was ready to go and he embraced me and said he would see me in the next life. I then noticed some people in the school tent and I told Ray Jones I was going over there to tell them goodbye. On my way over I looked back and saw Jones was not looking at me. I just ran towards the bushes.

Feeling “hungry and cold,”[40] Clayton sneaked his way back into Jonestown to change his clothes and locate his passport. He then made his way towards Port Kaituma and arrived at a Guyanese local’s house to report on what had happened.

Despite the compelling nature of Clayton’s testimony, it was met with what can best be described as ridicule and utter confusion by the magistrate and prosecutor, according to a Los Angeles Times reporter.

There were some people who thought Stanley Clayton was slow-witted. He spoke, when he spoke at all, with deliberation and the contracted idiom of the black backstreets of urban America. It was a language that was in- comprehensible and unacceptable to the two East Indian officials who saw it as their responsibility to recast his words in a kind of bureaucratic clay. In the process, they made it clear what they thought of Stanley Clayton.[41]

The magistrate may have misinterpreted or, worse, flatly ignored Clayton’s words. Still, it does not necessarily hinder his credibility. It is understated to say that Clayton has one of the most essential, if not unique, accounts. Excepting elders Grover Davis and Hyacinth Thrash – who were purported to have been asleep – Clayton spent the most time in Jonestown during the deaths.

Like Rhodes, Clayton received an equal amount of attention from the press. Such an exceptional story was well in demand, and certain unnamed survivors reportedly “sold their exclusive story several times.”[42] This resulted in many exaggerations and unverified claims circulating surrounding the deaths, including Clayton’s own account.[43]

Years later, for example, Clayton adamantly insisted “that Marceline dragged people to the vat of poison” and “that he saw a sharpshooter kill [Ann Moore].”[44] He had never once mentioned these claims at any time before, including the inquest, even though there is no reason he would fail to bring up such claims until decades later. In addition, many have questioned the fact that Clayton, after making a daring escape, returned to Jonestown “to, of all things, look for his passport.”[45] Surely, in hindsight, it seems illogical for Clayton to make such a move. It is important to remember, though, that in high-stress situations, individuals tend not to act with clear logic, and prefer riskier decisions.[46] Chaos can distort perceptions and decisions, leading to actions that may seem irrational in retrospect but that made sense under the intense pressure of the moment.

One other testimony was also heard that day. Detective Inspector Vernon Gentle, who accompanied Commissioner Roberts to Jonestown on November 20, recorded the list of identifications that Odell Rhodes made.

*****

The next day, December 16, the inquest would hear five more testimonies, including three survivors: the Carter brothers, Tim and Mike, and Mike Prokes.

The Carters and Prokes had already been heavily scrutinized in the media. Out of the seven survivors who escaped the deaths in Jonestown, these three were the only ones allowed to do so by the community’s leadership. Accordingly, from the start, the media approached the three men with suspicion. With nearly everyone in Jonestown dead – including those who were responsible for the deaths – it was both easy and sensational to shift blame towards the very few who did survive, chiefly the three. The media sought instant, digestible answers for the deaths. Ambiguities and nuances were an afterthought.

The Carters and Prokes were understandably under great pressure and anxiety. Rumors had circulated among American and Guyanese authorities that the three men had a possibility of being charged,[47] although no one could provide an answer on what for. As Tim Carter told me, Skip Roberts told him that they were being held in custody as “material witnesses.”[48] They were given little other information. In most other tragic situations, witnesses can reasonably expect to have access to legal counsel to prepare for their statements. The Carters and Prokes – along with the rest of the survivors – did not. Considering the many rumors circulating in Guyana, their lack of legal counsel undoubtedly concerned them.

Forty-five years later, Mike Carter expressed his anxiety over the inquest to me.

We didn’t have any legal representation. But we didn’t have anything to hide either. We weren’t guilty of anything. We were certainly nervous. You would expect they want to point the finger at somebody – probably under a lot of pressure and there weren’t a lot of people to say that these are the people to blame. It was certainly to go in there and share what we know because, again, we didn’t do anything wrong.[49]

Furthermore, Mike Carter explained his experience of testifying at inquest:

I remember taking the flight out to Matthews Ridge and going to testify. I was really nervous only because you just didn’t know – or I didn’t know what to expect. I’m freaking out. I was freaking out when we were in that holding cell. This was not good. Conditions were pretty bad. I didn’t want to go back to that, but I also didn’t want to go and perjure myself and or do anything illegal at the stand. … It was pretty scary for me. I was twenty and we had just dealt with all this trauma.[50]

Mike Carter was the first of the three to testify. As one of Jonestown’s radio operators, Mike spoke primarily of his interactions over the radio with Sharon Amos at the Temple’s Lamaha Gardens headquarters, and relayed updates of Ryan’s visit on November 18.

I was then in the radio room. I sent a message to the headquarters at Lamaha Gardens, Georgetown that everything was going well; the message was sent to Sharon Amos. About 1.30p.m. Mr. Dick Dryer [Dwyer] from the United States Embassy in Guyana came to the radio room and sent a message asking for another plane to carry out settlers. The embassy promised to send one. Mr. Dryer returned about twenty to thirty minutes later and sent a message to Sharon Amos saying that a family of seven persons and two other individuals wanting to leave Jonestown and she should relay this message to the United States Embassy in Georgetown. The first message was also relayed through Sharon Amos. A message came back through Sharon Amos that United States Embassy was sending a plane capable of carrying five persons. About one hour after Mr. Dryer returned again and asked me to send another message that another twelve persons wanted to leave. I pass this message to Sharon Amos. About one hour after this arrangements were made for the visitors to leave together with those settlers who desire to leave.

As it happened, the radio conversation that Mike testified about was recorded and released to the public.[51] His conversations with people in Jonestown that day were not. In his testimony, Mike spoke of an early interaction with Maria Katsaris, who had asked him to fake power problems as an excuse to shut off the radio connection with Lamaha Gardens. About an hour later, Katsaris approached Mike and his brother Tim to ask if they would help assist Prokes with carrying a “heavy suitcase.”[52] After returning to his cottage to change clothes, Mike explained that he headed to Jones’ home – far away from the main pavilion – and at around 5:30 p.m., the three men made their way out of Jonestown. As differentiated from his brother, who had painfully come across his wife and child as they were dying, Mike said that he did not witness any of the deaths in Jonestown.

After changing I went to the West House where Jim Jones lived. This house has three rooms. … Maria Katsaris been handed me a pistol and also handed Mike Prokes one and told us if we were caught we were to kill ourselves. I subsequently learnt that suit case had money. At the same time she handed us our passport and also handed to Mike Prokes Timothy Carter’s passport. … I asked Prokes where we were to go and he said we were to go to the embassy in town. Maria Katsaris had bid us farewell, we were awaiting Timothy Carter and he arrived about this time. I thought there was going to be some trouble and one of the things was suicide. We went to a position outside the settlement. This was around 5.30 p.m. I could not hear the public address system. On my leaving I saw no dead bodies.

Verifying Skip Roberts’ claim that they had helped recover the money from Jonestown’s banana grove, Mike stated that they had indeed first stopped and dropped a portion of the suitcase’s contents there. The second-to-last-page of Mike’s testimony is completely missing from the record, which likely detailed the rest of their escape and their encounter with Port Kaituma’s police.[53]

The first place we stopped was in a banana field in the settlement. This banana field is about 1500 yards over a hill and out of sight of the pavilion it was also out of hearing of public address system. We sat in the field and had a discussion, Mike Prokes had said that he learnt from Maria Katsaris that things were out of hand and they were going after Congressman Ryan. Prokes unzip the case and then I saw the contents which consisted of foreign currency, Guyana currency to smaller extent, I saw three boxes of jewelry, rings and necklaces and then I saw an envelope it was addressed to the Soviet Embassy in Georgetown. I opened the envelope and found at last to typewritten sheets of paper, it was too dark to read. It was signed. We took out six packs of foreign currency; each packet measured about four to five inches high and the length of an ordinary United States currency note. We dug six holes and buried the money in the same location; money was in plastic–

Mike’s testimony stands out in particular, as he was one of Jonestown’s radio operators, and other than Deborah Layton, who fled Guyana in May 1978, and Paula Adams, who was in Georgetown on the day of the deaths, Mike was one of the few who survived. His knowledge of Jonestown’s radio operations and tapes was instrumental in leading the GDF to recover boxes of audio tapes on November 20.[54] Although his role as a radio operator may have granted him access to outside information not received in Jonestown, he, like other members, still was not privy to the intricate inner workings of the Temple.

The next to testify was Mike’s older brother, Tim Carter.

The beginning of Tim’s testimony centered on his various roles in the Temple – such as his secretarial work, serving as an organizer for Jonestown’s Medical Department, customs work in Georgetown, and public relations work. It should be noted that whereas the prior survivors to testify – Odell Rhodes, Stanley Clayton, and Tim’s brother Mike – had lived in Jonestown, Tim spent much of his time in Georgetown.

He was nevertheless present during some of the key events in Jonestown’s history, including the Six-Day-Siege, and various times where gunshots were heard.

In September, 1977 over a period of several days six rounds were fired at Jonestown. I did not see who fired those rounds no one was injured. I was at different places at the time of this incident in September, 1977. In November there was an instance of a discharge of one round. I did not see [the] person who discharged round. In December, 1977 also one round discharged again I did not see the person who discharged round. No one was injured on any of these occasions.

Tim did not give any details of his visit to the U.S. in the fall of 1978 – specifically his visits with the Concerned Relatives to inquire about the whereabouts of Teri Buford, although he did mention it.

I got information that Congressman Ryan and a Party were going to visit Jonestown, this was when I was in the States in October; November, 1978. While in the States I had discussions with relatives in the States of settlers in Jonestown and on my return to Guyana I told Jim Jones about this proposed visit of Congressman Ryan and the relatives of the settlers.

The rest of Tim’s testimony focused on his escape from Jonestown, which corroborates what his brother previously testified.

I then left with them behind the kitchen, passed the generator, crossed the road and went at the end of the Banana Grove. The suitcase was very heavy, when we got there we buried some money, took some and put some in money belts. My brother wore one and I wore one. From there we went to the chicken area where we deposited the money in a chicken feed bag and left the suitcase. In the suitcase was a letter addressed to the Soviet Embassy, Georgetown. As we were going we were talking and I told Prokes and my brother about what I saw at the pavilion, Prokes said our destination is at the Embassy. I spent about half hour at the chicken farm and I left in the direction of Jonestown road, I did not see any vehicle going towards Jonestown on leaving. While we were walking we were trying to avoid being seen as much as possible. We reached the Railway line and after resting a few times we finally reached Port Kaituma.

Of the six survivors who testified at the inquest, Tim Carter has without a doubt had the greatest public presence over the intervening years, giving countless interviews for documentaries and TV shows. Unlike his testimony at the inquest, these later interviews are heavily cut, edited, used in various contexts, and are rarely kept in their original form. On the other hand, many of the media interviews given in the immediate aftermath often occurred in a hectic manner, without much context or elaboration. This contributes to what may seem to be inconsistencies and discrepancies. In addition, as survivors learn of new information from each other, their own retrospectives develop and change.

Mike Prokes was the final witness from the group to testify. Contrary to what would be expected of one of the Temple’s public relations leaders, Prokes’ testimony was starkly short, the second shortest of all the survivors who spoke at the inquest. Rather than describing his well-documented public relations duties for the Temple, he focused on his work in the Jonestown community.

One of my jobs was to purchase and supply spare parts for the Agriculture machinery. I also worked as a School Teacher, teaching Night school students. I taught English to children in their Mid-teens. I also worked in the Cassava Crew.

The rest of his testimony related to Ryan’s visit to Jonestown, noting that he was a part of the delegation that greeted Ryan and the press in Port Kaituma on November 17. After Ryan and the defectors left the following day, he was met by a frantic Maria Katsaris, who asked him to carry out a mission: to transport a heavy suitcase to the Soviet Embassy in Georgetown. Again, his account corroborated many of the details given by the Carter brothers.

We went behind the kitchen, passed a generator, crossed the road into a field. We stopped in the banana field as the suitcase was too heavy. There in the banana field we buried some money about 8 to 10 plastic packs. There were jewelry in small boxes; there were also two money belts. There were two letters addressed to the Soviet Embassy. In one of the envelopes were typewritten papers and the other letter also typewritten. There are also two passports in the suitcase, one was in the name of an old lady and the other I did not look at. I knew it was an old lady from the picture in the passport. We then went to livestock area and there we deposited money into a chicken feed bag and left the suitcase there. We got some water, rested and left and when along road to Port Kaituma.

In March 1979 – three months after his inquest testimony – Mike Prokes committed suicide following a press conference in a motel room in Modesto, California. It appears that his inquest testimony presaged a great change in his attitude after the mass deaths. The Carters and Prokes were hounded by the media when they first arrived at the Park Hotel in Georgetown on November 25. In all the interviews that have survived, Prokes is noticeably quiet. Whenever he did grant comments, they were, more often than not, dismissive.[55] His hushed attitude is reflected in his testimony. Many, including some of those close to him, believed that Prokes was disenchanted following the collapse of Peoples Temple. True or not, his inquest testimony revealed a demeanor that contrasted sharply with his earlier promotion of the Temple’s virtues in Guyana.[56]

The most relevant testimonies for comparison from the Carters and Prokes exist in the form of their police statements given to the Guyanese police. Forwarded to the FBI as a part of their RYMUR investigation in 1979, their statements seem consistent with their inquest testimonies. Regardless, there are sections of their statements which supposedly detail their escape that have never been publicly released. Additionally, the Carters and Prokes are among the few survivors who are known not to have conducted an interview with the FBI upon their return to the U.S.

As Tim explained to me, it wasn’t until they arrived at the John F. Kennedy Airport after more than a month in Guyana that they received legal representation.

We were down in the tombs of JFK talking to the FBI. There were about seven different agencies. We all got off the plane and all got separated, although Michael and I were kept together. The FBI was there, the ATF, CIA, Secret Service, I’m sure the NSA was there under the guise of something. It seems to me the State Department was there too. … We’re talking for maybe five minutes and [our attorney, Jeremiah Gutman] walks in and goes ‘I am their attorney. This interview stops now.’

Since three survivor testimonies were heard in a single day – the most so far – it attracted much media attention. After furnishing their statements at the inquest, Tim recalled that he and Prokes spent the night at a “boarding house in Matthews Ridge,” where they had talked to New York Times and Los Angeles Times reporters for a good “three to four hours.”[57] Besides the inquest itself, Tim noted that this conversation demonstrated to the reporters that the Temple survivors were, in fact, intelligent.

Mike Prokes left behind several statements in the wake of his suicide,[58] including one that produced a major revelation: the existence of what is now known as the death tape.[59] As Prokes said, Charles English, a Foreign Service Officer at the American Embassy, “described parts of the tape to myself, Tim Carter and two reporters” in Matthews Ridge. For whatever reason, the tape had not been presented or even reviewed at the time of the inquest. Despite the tape’s importance, Prokes stated that he, English, and Skip Roberts speculated that the tape was withheld from the inquest – and the general public – as it was “an embarrassment to the United States.” This was based on the perception that “the people of Jonestown were not coerced into taking their lives.”[60] Such details would complicate any verdict reached at the end of the inquest. The incomplete testimony given during the proceedings would leave everyone – the magistrate, the jurors, and the press in attendance – perplexed. There were substantial testimonies provided both by Jonestown survivors and by Guyanese authorities, but nobody could seem to gain a complete perspective of what really unfolded on November 18.

Following the Carters and Prokes that day came two more testimonies, from two Guyanese security guards – Paul Adams and Gilbert Gomes – who had encountered the three men when they arrived in Port Kaituma after leaving Jonestown. Neither of the security guards are known to have given any other statements or interviews.

Both statements were brief. They precisely described their encounter in overhearing and confronting the three men.

As a result of something I heard a reported for duty at 9.00 p.m. (early) In order to get to my post I had to walk along the train line and I heard voices. From their accent I decided they were settlers from Jonestown. I estimated there were about five persons speaking to one another. I was not able to make out what they were saying. At my workplace I told the Security guards Sealey and Kansanalli what I heard. I remained on duty at my post and about 11.55 p.m. security guard Gilbert Gomes told me something; as a result of what he told me I went to Port Kaituma waterfront and hid after seeing three Americans; as soon as they were about to pass me I halted them with my gun and ordered them to go to the out post at Port Kaituma.

I saw three persons passing down at the Waterfront I ran and called Durga Persaud. I ran then about three rods from the Security Guard room. They were passing going towards the waterfront. I called Durga Persaud and he and Paul Adams returned with the said three men. Paul Adams took from them all their possessions including two revolvers, a quantity of money, $48,300.00 US currency and $974 (G.) currency; all these things Police took possession of; Paul Adams also took five passports from them.

*****

December 17, the final day of the inquest to the jury, consisted of a second statement by Commissioner Skip Roberts and the testimony of one more survivor.

In a dramatic presentation, Roberts read numerous letters and notes,[61] including a suicide note attributed to Ann Moore[62] and several financial letters[63] found in the suitcases left behind by the Carters and Prokes. The financial letters were of great interest as they substantiated the Carters and Prokes’ story of being cash couriers bound for the Soviet Embassy. Aside from prior statements made by the Carters and Prokes to the media regarding their mission, the inquest was the first time “the letters, and their contents [were] publicly revealed.”[64] The letters consisted of multiple typed and handwritten notes left behind by Annie McGowan – a loyal elderly member who allegedly allowed Temple bank accounts to be opened in her name – Maria Katsaris, Marceline Jones, and Carolyn Layton. The notes all bequeathed the Temple’s millions to the Soviet Union.

Roberts had an additional revelation. Between December 1 and 3, he stated, more suitcases and cash had been found along the railroad tracks leading into Port Kaituma. The contents were reportedly confiscated and held by the police. Initially, the Carters and Prokes apparently specified only one suitcase, which they had described as a “package.”[65]However, the Carters and Prokes mentioned in their first police statements that they walked near the railroad tracks on their escape into Port Kaituma,[66] and acknowledged to Guyana police that they carried multiple suitcases.[67]Furthermore, in later years, Tim Carter steadily maintained that they each carried a suitcase.[68]

It may be hard to understand the exact reason that they did not indicate all three suitcases early on. They were not the only survivors to deliberately secrete information. It should be emphasized again that after returning to the U.S., survivors were afforded the opportunity to provide a more comprehensive account of their experiences and to disclose additional details. Foremost, they had the advantage of hindsight. Many of the survivors at the inquest were still in shell-shocked condition. They had yet to process their own grief and confusion, let alone comprehend their own survival. Their inquest testimonies and early statements must be taken in tandem with the context of the Jonestown aftermath – that is, of an atmosphere marked by paranoia, confusion, and anxiety.

Herbert Newell was the last survivor before the Guyana inquest. As differentiated from the other survivors, Newell was the only witness who was not present in Jonestown when Ryan and his delegation left the community for the Port Kaituma airstrip on November 18. Indeed, as Newell explained, he and Clifford Gieg were asked to take the Temple’s ship, the Cudjoe, down the Kaituma River to the village of Kumaka. Newell did not elaborate on the reason for doing so, though he explains that they were told to return to Port Kaituma the next day. They never had the chance. The Cudjoe was seized by the GDF.

We checked the engine and left Port Kaituma around 10 AM and reached Kumaka about 3:45 PM on that said day 16th [18th] November, 1978. I was told to wait until the next day I then take the boat back to Port Kaituma. We remained there until about 12 o’clock that night when the Guyana Defense Force took charge of the boat and took us to Mabaruma Police Station.

Newell’s testimony brought forth the unavoidable question: what was the purpose of taking the Cudjoe away from Port Kaituma? But like all the previous testimonies, it produced more questions than answers.

*****

All of the testimonies were complete, and the inquest was nearing its verdict. The prosecutor “had instructed the five jurors to go home and contemplate the new developments for three days before making any decisions.”[69] On December 22, the jurors returned their verdict.

Some persons or persons unknown is responsible for the death of James Warren Jones. Jim Warren Jones and persons unknown our criminally responsible for the deaths of the 910 persons. Ann Elizabeth Moore committed suicide and Maria Katsaris drank the brew voluntarily she committed suicide.

In short, with the exceptions of Jim Jones, Ann Moore, and Maria Katsaris, the jurors found that the rest of the Jonestown residents had been murdered. Moreover, an open verdict was returned involving the death of an “unidentified Caucasian male, about six feet tall.”[70] No other information was provided in regards to the individual, although it was believed that the man had died from gunshot wounds.[71] There appear to be no follow-up reports or references to this specific person. A review of Dr. Mootoo’s various statements to American authorities found no mention of individuals having gunshot wounds except for Jim Jones and Ann Moore. In addition, there was no indication of anyone matching that description or manner of death in the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology and FBI’s release of body identification information in late 1978 and early 1979.[72] Only seven autopsies were performed on those who died in Jonestown – including Jones and Ann Moore – so it remains unknown to this day who the man might have been and whether or not he died from a gunshot wound.

The verdict came with strings attached. It was later revealed that the jury’s official verdict was not its original conclusion. After initial deliberation, the jurors considered Dr. Mootoo’s claim that “Jones was shot from a very close range in the ‘suicide area,’”[73] and decided “that Jones had committed suicide,” This verdict was not at all satisfactory for the magistrate and prosecutor, who apparently were determined to conclude that the deaths were murders and that Jones was not responsible for his own death. The magistrate angrily yelled out – mocking the jurors – and questioned their evidence.[74] He also pointed out that Dr. Mootoo had supposedly said the “gun was found 20 yards away from Jones’ body”[75] – although others have reported the gun being much closer. The jurors entered deliberation again, and after ten minutes, reached their final verdict.

Following the delivery of the second verdict, the head of the jurors, Albert Foreman, elaborated on his thoughts.

“The man made people believe he was a god and naturally they will move to his command[.] The man is responsible. Jones is responsible morally and criminally.”[76]

No matter the evidence, it was impossible to piece together what really happened. As Foreman best put it: “I was not there, so how will I ever know?”[77] But with a verdict on the record, the inquest achieved its most practical goal: it allowed for death certificates to be issued.

In retrospect, the inquest failed to provide any concrete answers involving the actual deaths. If anything, it sparked mystique, speculation, and, of course, suspicion. This excerpt from an article written two days after the inquest for the Guyana Chronicle captured the general attitude surrounding the verdict.

But now that the six-day inquest has ended, the mystery shrouding the Jonestown disaster – the tragedy that has no parallel – seems to have deepened if anything. And, somewhere in the midst of it all, I smell a rat – nay, a few rats.[78]

In the immediate aftermath of the verdict, there was speculation that the inquest would lay the groundwork for the future trials in the U.S. Certain Guyanese officials went so far as to predict that trials in the U.S. would lead to many convictions.[79] Despite early anxiety of the survivors who testified at the inquest that they would be charged with crimes, no one ever was. Only Larry Layton – who was arrested at the airstrip for his role in the shootings – was ever tried and convicted in the U.S., and that was after a Guyanese jury had found him not guilty in the incident. Layton’s name was not mentioned during the inquest.

Perhaps if the inquest had allowed for a greater amount of evidence to be seen – such as the death tape – and had allowed for witnesses to be cross-examined,[80] a more trustworthy verdict could have been reached. But given the political tensions rampant in Guyana from the tragedy, it comes as no surprise that the inquest felt rushed.

Nevertheless, the greatest issue with the inquest is not its verdict but instead lies with its record. The inquest was not a verbatim record of the witnesses’ accounts. There was no court reporter or stenographer present. Rather, it was entirely left to the magistrate to write down the testimonies of the witnesses. This resulted in what may be many misinterpretations and omissions of witnesses’ accounts. A reporter summed up the credibility of the inquest this way.

The pace of the proceedings ranged from merely sluggish to virtually imperceptible. No court reporter was present; instead, Bacchus kept the record himself in laborious longhand. He muttered the testimony aloud as he wrote it down, providing a surreal Caribbean echo to the words coming from the witness stand.[81]

An analysis of the news articles written about the inquest also reveals a number of additional quotes and statements made by witnesses – including by Commissioner Roberts – that were not included in the official record. The inquest was made out to be a comprehensive investigation of the witnesses. But like every other document or statement, it cannot be taken with utmost certainty. The transcript of the inquest consists only of 47 photocopied pages forwarded to the FBI. There were no other documents of deliberations, or texts of the questions prosecutors asked.

This is not to say that the inquest lacks any merit. Perhaps only decades later can the full significance of the inquest be recognized.

Foremost, in comparison to the two criminal trials conducted in the U.S. and the many personal investigations in the past four decades, the inquest benefited from the timely testimony of numerous Jonestown survivors. It also had direct access to Jonestown, in spite of the fact the encampment had already been looted. With knowledge of the faultiness of memories and how they become reconstructed overtime, the testimonies at the inquest – even with the omission of certain facts – are more candid than recollections given in later years. It can reasonably be concluded that the inquest provides one of the most comprehensive collections of survivor accounts ever to exist.

It is easy to insist that survivors provide a completely truthful account. The reality is such a perfect, flawless account could never exist. From the second survivors stepped foot out of Jonestown, their new memories were already being influenced by distress and shock. As they encountered new information – sometimes inaccurate – from a myriad of sources, their own perspectives changed. The inquest must be understood in its context: the atmosphere following Jonestown and at the inquest was one of fear, confusion, and distrust. It functioned as a de facto fact-finding investigation for a nation that paradoxically wanted nothing more to do with Jonestown or Jim Jones. Both Guyanese and American authorities were charged with providing complete and immediate answers for a tragedy unlike any they had never dealt with. Pressures by their governments, the press, the relatives of the dead, and themselves, affected the treatment of survivors. So too, inquest jurors assumed that they knew everything. The media thought so as well. They did not. The memories the witnesses put forth at the inquest were really just stitches of their current emotions, beliefs, and fragments. More than anything else, though, the inquest revealed just how little the survivors knew about Peoples Temple.

*****

Finally, with the inquest closed, there was no reason to require the remaining survivors to stay in Guyana. Many other survivors, including most of those staying at the Temple’s Lamaha Gardens headquarters and at the Park Hotel, had departed Guyana in late November or earlier in December. Those who remained had either been called to testify at the inquest, or at Larry Layton and Chuck Beikman’s preliminary hearings, or they had decided to stay in Georgetown.

The seven Jonestown survivors who testified at the inquest believed that after they furnished their statements, they would be allowed to leave Guyana. Clayton, Rhodes, and Newell, for example, received clearance to depart Guyana in the immediate days after testifying.[82] Despite the fact that Clayton was allowed to leave Guyana had he supposedly “exchanged marriage vows with a Guyanese girl”[83] a few days after the inquest, according to the Guyana Chronicle.

The clearances for departure did not extend to the Carter brothers, though, and the situation left them uneasy. In an interview with the Idaho Statesman, Tim Carter voiced his concern.

It worried us … because both official and unofficial sources said we would be allowed to leave after we testified at the inquest. … We gave our testimony last weekend but we have been told we still have to stay. We don’t know why, because another witness was allowed to go.[84]

On December 23, the Carters and Prokes finally received permission to leave.[85] Mike Prokes didn’t wait around for anyone to change their minds, and the next day, December 24, he departed Guyana without alerting Guyanese or American officials.[86] Since all survivors were supposed to be accompanied by sky marshals, and since he hadn’t, his secret return seemed suspicious to many.

I have no idea how [Prokes] did it. You had to get tax clearance. It’s an actual slip of paper that comes from the Guyana Tax Office that says that you don’t owe taxes. You don’t just walk in and get one. It takes at least a day. Everybody was watching us: the FBI, CIA. Somehow Prokes gets on a plane and makes it back to Modesto before anybody knows it?[87]

Nevertheless, on December 29, five days after Prokes left, the Carters and six other survivors left Guyana.[88]

Putting Guyana behind them for many survivors also meant putting the inquest behind them. The survivors who testified hadn’t even entirely been sure of its purpose, and, as Tim Carter acknowledged, he “didn’t even know what came out of the inquest.”[89] Unbeknownst to them, in the following years, the inquest would become one of the most crucial documents in interpreting the events of November 18 through the perspective of survivors.

*****

For as long as studies of Peoples Temple continue, there will probably never exist a definite account of what really happened. At a surface level, the inquest had little influence on later investigations that occurred on American soil. Regardless, the endeavor produced a collection of witness testimonies – from both survivors and the Guyanese – unlike any other. Though imperfect, the inquest is symbolic of the turbulent aftermath of Jonestown. Decades later, perhaps the inquest can be recognized not as the absolute truth, but instead serve as a testament to the complex reality of reconstructing a tragedy that not a single testimony can thoroughly answer. The closest way anyone can get to a truth is to read and compare as many sources as possible.

Footnotes

[1] Josh Freed, “We Change Our Memories Each Time We Recall Them, but That Doesn’t Mean We’re Lying,” CBC, n.d.

[2] Cable 3929, from Georgetown to State, November 25, 1978.

[3] Cable 3811, from Georgetown to State, November 20, 1978.

[4] “Dr. Reid Reports To Nation on Jonestown Disaster,” Guyana Chronicle (Part 1) (Part 2), November 25, 1978.

[5] The coroner’s inquest into the mass deaths was technically the sole investigation to occur on Guyanese soil. However, there were additional inquiries and trials taking place concurrently into the role of various individuals in the mass deaths, including Charles Beikman, Larry Layton, and Stephan Jones.

[6] “Peoples Temple inquest opens today,” Guyana Chronicle, December 13, 1978.

[7] It should be noted that nearly all of the Guyanese government’s official records on the Jonestown aftermath – with the exception of a number of documents that were borrowed by and photocopied by the FBI – were destroyed, along with many other Guyanese government records, in a 1980 fire in Georgetown. This has created a challenge in piecing together the timeline of the Guyanese government’s handling of the aftermath and the coroner’s inquest (e.g., jury and witness selection, bureaucratic paperwork, etc.). However, most dates can be pieced together through the diplomatic cables and newspaper accounts that did survive.

[8] Cable 313461, from State to Georgetown, December 12, 1978.

[9] Although the request for an American consular officer to testify was approved, there is no record of an official ever doing so.

[10] Cable 313253, from State to Georgetown, December 12, 1978.

[11] Peter H. King, “Jonestown: impossible questions, 5 villagers bear burden,” San Francisco Examiner, December 15, 1978.

[12] Cable 4285, from State to Georgetown, December 15, 1978, available.

[13] Why are there differences in the final death toll, and why do those differences still persist? This count does not include the deaths of Sharon Amos and her three children in Georgetown.

[14] The 33 number was likely a transcription error. Roberts’ count of bodies found away from the pavilion (13 in Jones’ house; 9 in the elderly dorms) adds up to 22, not 33.

[15] Rebecca Moore, A Sympathetic History of Jonestown: The Moore Family Involvement in Peoples Temple (Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 1985), 80.

[16] Moore, A Sympathetic History of Jonestown, 80.

[17] Peter H. King, “In Guyana the mystery still grows,” San Francisco Examiner, December 18, 1978.

[18] Moore, 80.

[19] Rebecca Moore, “The Forensic Investigation of Jonestown Conducted by Dr. Leslie Mootoo: A Critical Analysis,” Jonestown Institute, August 18, 2018.

[20] AP, “Most Jonestown Deaths Not Suicide, Doctor Says,” New York Times, December 17, 1978.

[21] Joseph B. Treaster, “Jury Blames Jones for Guyana Deaths,” New York Times, December 23, 1978.

[22] “Saturday Night Horror,” Guyana Chronicle, December 6, 1978, Chronicle Special edition.

[23] Tim Carter, interview by Aliah Mohmand, January 16, 2024.

[24] It is highly probable that the early identifications made by Odell Rhodes, the Carters, and Prokes in the presence of Guyanese officials were used to construct the first list of those identified as deceased, which was released by the U.S. State Department. The same list would then be reprinted in numerous newspapers around the U.S. to notify next-of-kin.

[25] Charles T. Powers, “Inquest Tour Makes Coroner Ill,” Los Angeles Times, December 15, 1978.

[26] Powers, “Inquest Tour.”

[27] Powers, “Inquest Tour.”

[28] Peter H. King, “Charts reveal organization of Jonestown,” San Francisco Examiner, December 15, 1978; see also Charles Krause, “Chart Found in Jonestown Details Structure of Cult,” Washington Post, December 14, 1978.

[29] Powers, “Inquest Tour.”

[30] King, “5 villagers bear burden.”

[31] David Vidal, “Coroner’s Jury and a Cult Survivor Visit the Death Scene at Jonestown,” New York Times, December 15, 1978.

[33] Jonestown Petition to Block Rep. Ryan.

[34] Ethan Feinsod, Awake in a Nightmare: Jonestown, the Only Eyewitness Account (NYC, New York: Norton, 1981). Clayton’s account also provided the basis for much of the Jonestown narrative in Kenneth Wooden’s book The Children of Jonestown (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1981).

<[35] RYMUR Serial 2242, from San Francisco to FBI, July 17, 1979.

[36] Feinsod, Awake in a Nightmare, 202.

[37] Feinsod, Awake in a Nightmare, 209.

[38] Hal Arkowitz and Scott Lilienfeld, “Why Science Tells Us Not to Rely on Eyewitness Accounts,” Scientific American, January 1, 2010.

[39] Arkowitz and Lilienfield, “Why Science Tells Us.”

[40] Feinsod, 205.

[41] Charles T. Powers, “Jonestown Inquest – a New Glimpse,” Los Angeles Times, December 21, 1978.

[42] Tim Cahill, “In the Valley of the Shadow of Death: Guyana After the Jonestown Massacre,” Rolling Stones, January 25, 1979.

[43] While reading The Children of Jonestown, I came across many uncorroborated claims and details made surrounding the deaths, and accordingly decided not to use his account in the book. Many of the inaccuracies may of course be attributed to the changing nature of memory, previously discussed.

[44] “Back to the Sources,” Jonestown Journal, March 15, 2018.

[45] Courtney Gibson, “Who Killed Jim Jones,” Guyana Chronicle, December 24, 1978.

[46] Anne Trafton, “Stress Can Lead to Risky Decisions,” Massachusetts Institute of Technology, November 16, 2017.

[47] Cable 3853, from Georgetown to State, November 22, 1978.

[48] Tim Carter, interview by Aliah Mohmand, June 19, 2024.

[49] Mike Carter, interview by Aliah Mohmand, September 19, 2023.

[50] Mike Carter, interview by Aliah Mohmand, September 19, 2023.

[52] ABC News: Jonestown Interview with Mike and Tim Carter, December 1, 1978.

[53] It might be speculated that the missing page from Mike Carter’s testimony was dubiously lost or purposely removed. That is probably not the answer in this scenario. The Guyanese government and its relationship with the FBI and the U.S. State Department were marked by miscommunication and the mishandling of information.

[54] Shannon Howard, interview with Mike Carter, Episode 11 Ockham’s Razor, Solving the Mystery of Q875, Transmissions from Jonestown, podcast, November 18, 2018.

[55] Archivo Difilm Templo del Pueblo: Interview with Mike and Tim Carter and Michael Prokes.

[57] Tim Carter, interview by Aliah Mohmand, January 26, 2024.

[58] The Death of Michael Prokes.

[60] Michael Prokes’ Statement to the Press, March 13, 1978.

[61] RYMUR Serial 1509, from Georgetown to State, December 17, 1978.

[62] Annie Moore’s Last Letter.

[63] Financial Letters of November 18

[64] Jerry Belcher and Leonard Greenwood, “Who Escape Say They Had to Abandon Money,” Los Angeles Times, December 18, 1978.

[65] ABC News Interview: Jonestown Interview with Mike and Tim Carter, November 25, 1978.

[66] RYMUR Serial 2153, from San Francisco to FBI, April 2, 1979.

[67] RYMUR Serial 1441, from Georgetown to FBI, Dec 27, 1978.

[68] Jeff Guinn, The Road to Jonestown: Jim Jones and Peoples Temple (NYC, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018), 446.

[69] Peter H. King, “In Guyana the mystery still grows,” San Francisco Examiner, December 18, 1978.

[70] RYMUR Serial 1407, from Georgetown to State, December 22, 1978.

[71] Joseph B. Treaster, “Jury Blames Jones for Guyana Deaths,” New York Times, December 23, 1978.

[72] RYMUR Serial 1730, from FBI to State, December 14, 1978.

[73] Charles Krause, “Guyanese Panels Rules All but 2 Were Murdered,” Washington Post, December 22 1978.

[74] Joseph B. Treaster, “Jury Blames Jones.”

[75] Charles Krause, “Guyanese Panels.”

[76] Treaster, “Jury Blames Jones.”

[77] Krause, “Guyanese Panels.”

[78] Gibson, “Who Killed Jim Jones.”

[79] Treaster, “Jury Blames Jones.”

[80] Treaster, “Jury Blames Jones.”

[81] Powers, “Jonestown Inquest.”

[82] Peter H. King, “Guyana says temple defectors free to leave,” San Francisco Examiner, December 19, 1978.

[83] “Love Blooms for Jonestown Survivor,” Guyana Chronicle, December 25, 1978.

[84] “Carters hope to return to U.S. within 10 days,” Idaho Statesman, December 20, 1978.

[85] RYMUR Serial 1410, from Georgetown to State, December 23, 1978. [Aliah originally has 100333]

[86] RYMUR Serial 2303-post, January 3, 1979.

[87] Tim Carter, interview by Aliah Mohmand, January 19, 2024.

[88] RYMUR Serial 1465, from Brooklyn to FBI, December 28, 1978.

[89] Tim Carter, interview by Aliah Mohmand, January 19, 2024.