[Editor’s note: This article originally appeared as “If you don’t love children, you don’t understand socialism” in Utopian Imaginings: Saving the Future in the Present, edited by Victoria Wolcott, 143-174 (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2024), and is reprinted with permission.

[Alexandra Leah Prince (they/them) is a U.S. cultural historian of American religions and Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, New York. They also work with their students as volunteer transcribers for this site. They may be reached at aprince@skidmore.edu.]

You goddamn miserable Christian. You wouldn’t say fuck but you’d stand by and let the Nazis kill children.

—Jim Jones, Sermon, November 1978

What a beautiful place this was. The children loved the jungle, learned about animals and plants. There were no cars to run over them; no child-molesters to molest them; nobody to hurt them. They were the freest, most intelligent children I had ever known.

—Annie Moore, member of Peoples Temple, from a letter she wrote on the last day at Jonestown

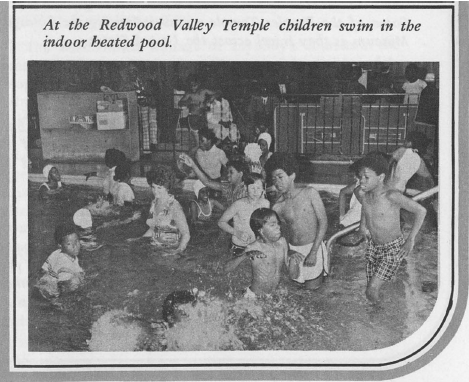

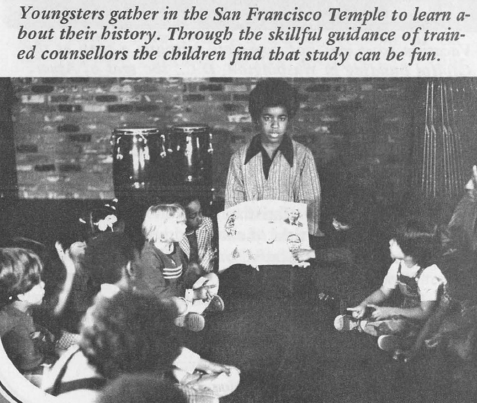

Children are everywhere and nowhere in the histories of Peoples Temple.1 Children occupied the church pews in Indianapolis and swam in the community pool in Redwood Valley. Children attended Peoples Temple schools and distributed newspapers to expand the reach of Peoples Temple in San Francisco. They sang in the Temple’s youth choirs and packed onto the community’s Greyhound buses for weeks-long missionary journeys across the country. Their small faces graced Peoples Temple publications, promotional materials, and the group’s music album in 1973. Infants, children, and teens comprised around a quarter of Peoples Temple members over its nearly two-decade-long history.2 And when Peoples Temple came to its tragic end on November 18, 1978, in Jonestown – the Peoples Temple agricultural settlement in Guyana – 304 individuals under the age of eighteen were murdered.3

Peoples Temple was one of the largest-scale and most enduring interracial utopian movements in the United States. The community succeeded Father Divine’s Peace Mission Movement as the twentieth century’s greatest effort to reimagine the boundaries of American race and class. From 1956 to 1978, Peoples Temples functioned as a Black-majority interracial church and communalistic political body dedicated to ending racial segregation, poverty, and the manifold social inequities the group believed were perpetuated by American capitalism and global imperialism.4 Its socialist ethic fostered housing and medical services for hundreds of seniors, free education and college, free healthcare, foster homes for children, and job training and rehabilitation for drug users, criminal offenders, and others who had fallen through the expanding cracks of the American welfare system and President Lyndon Johnson’s war on poverty.

Since the tragedy in Jonestown that claimed 918 lives, Peoples Temple members have been dismissed as the “brainwashed” followers of Jim Jones. In turn, Jones has been depicted by critics as a megalomaniac whose role in Peoples Temple was nothing more than a ruse to gain power and inflict abuse. A 1978 Time magazine cover published after the devastation at Jonestown referred to the group as the “Cult of Death,” cementing public understanding of Peoples Temple as a “dangerous, murderous cult.”5 “Jonestown became the most powerful negative metaphor in 20th century religious history,” observed author and minister Lowell D. Streiker in 1989.6 For decades, former members, relatives, and scholars of Peoples Temple have called for more nuanced historical considerations that push beyond pathological profiles of Jones and the sensationalist and reductionistic frameworks perpetuated by popular media. In the process, the people of Peoples Temple, with their diverse identities, backgrounds, experiences, and motivations, have been brought to the forefront.

A growing number of voices, such as religious studies scholars Rebecca Moore and Mary McCormick Maaga, historian James Lance Taylor, and writers like Sikivu Hutchinson, have offered more inclusive and complex lenses to consider Peoples Temple. Their examinations have advanced popular and scholarly consideration of the group’s Black majority, forefronted Black women’s roles and experiences, explored how Peoples Temple represented one of the largest and most significant Black movements of the twentieth century, and analyzed the dimensionality of women’s leadership.7 Such treatments of Peoples Temple fully acknowledge the multiple abuses and systems of power that deteriorated the vision of the community, and the paradox of Peoples Temple as both a utopian success and tragic failure.

Yet, despite repeated calls from scholars, former members, and relatives to reconsider, reexamine, and “take a second look” at Peoples Temple, the role of children and the youth within the movement – numerically, practically, and ideologically – has yet to be investigated. Children, including babies and teenagers, made up 36 percent of the Jonestown community in November 1978, the month of the tragedy.8 A total of 304 individuals aged seventeen and younger died; the majority of them were Black. Of that total, 190 were under the age of twelve.9 Many of the teens were Black urban youth.10 When children are mentioned or considered, the horror and sadness surrounding their untimely deaths has largely defined the scope of consideration. Frameworks of victimization and abuse continue to dominate accounts of children within Peoples Temple in keeping with trends within studies of children in new religious movements.11 An attendant preoccupation with threats to child safety have historically been foundational to anti-cult efforts more broadly.12 To be sure, the hundreds of children who were killed at Jonestown were victims, but their lives, and their influence on the broader movement of Peoples Temple, like those of the adult and senior members, cannot be fully understood or appreciated within a victimization or abuse framework.13

The definition of childhood is a shifting and culturally informed category. In the following, I examine the place and role of individuals from infancy to the age of eighteen with an emphasis on the pre-Jonestown era. I assume a child-centered lens in the methodology of childhood studies, which situates children at the center, to recognize how children, as both literal and figurative beings, shaped Peoples Temple. This lens enables children to be viewed as relational co-creators of Peoples Temple rather than the passive repositories of their parents and elders’ ambitions. However, unlike social scientific studies of children, I am not so much concerned with children’s views of the community and their religion, but rather with what we can further uncover about the daily dynamics, politics, and philosophy of Peoples Temple by examining how its vision of child welfare occupied a central role in the effort to build a more just society. To a lesser extent, I examine the education of teens to analyze the socialist models within which children were educated.

Speaking of the role of children in studies of religion, scholars Bonnie J. Miller-McLemore and Don S. Browning have remarked that “the neglect of children in the academic study of religion has not only robbed us of a deeper understanding of them, it has deprived us of an important angle of vision on understanding these diverse religions themselves.”14 While Peoples Temple was officially affiliated with the Disciples of Christ, and before that the International Assemblies of God, and many members were devout Christians, Jones and the movement more broadly had a complex relationship with Christianity and organized religion, with a large contingent of members avowing Communist, socialist, and atheist sensibilities. Nonetheless, McLemore and Browning’s sentiment conveys the utility of applying the lens of childhood to better understand the whole of a community. By examining how a community or religion understands and is influenced by children, we can access a critical dimension of their theology or what a group “truly cares about.”15 I explore the role and meaning of children and the youth ideologically, practically, as tools for Peoples Temple publicity and monetary solicitation, and finally as political battlegrounds. Through examination of remembrances by former members and relatives, newspaper articles, Peoples Temple publications, sermons, journal entries, poetry, and government documents, I demonstrate that children’s welfare was a core principle of the interracial socialist utopian vision of Peoples Temple, a critical foundation of the community that cannot be overlooked.16

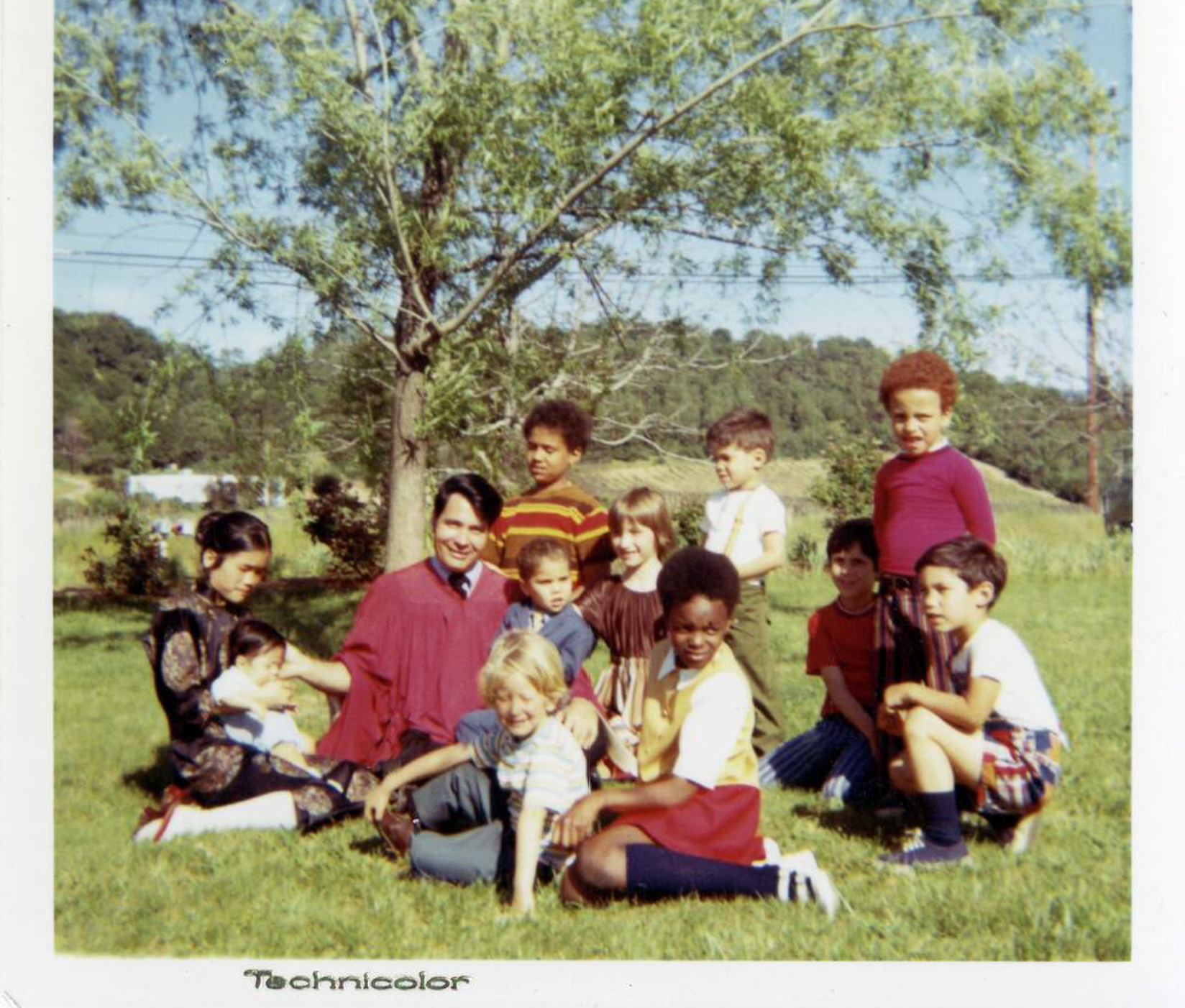

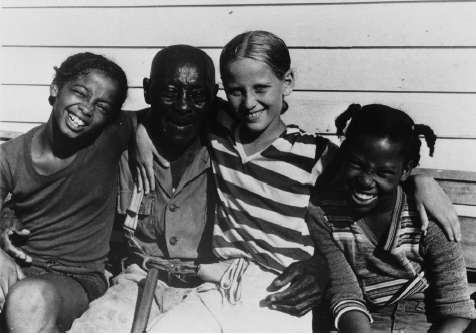

Human Family

Throughout Peoples Temple history, Jones’s formation of a multiracial “rainbow” family, or adoption of children from different racial backgrounds, became a popular means of allegorically relating Jones’s – and by extension Peoples Temple’s – commitment to racial integration. “Show us a man other than Jim Jones who has adopted children of all races,” proclaimed the August 1970 Peoples Temple newsletter.17 In the early 1950s, Jim and his wife Marceline were living in Indianapolis and working toward finding a home for the integrated church that would become Peoples Temple. They started their family by adopting Agnes, a child around the age of ten with Native American ancestry.18 In 1959, the Jones adopted three orphaned Korean children: Kun Eun Soon, Eun Ok Kyung, and Pac Chi Oak, who were renamed Stephanie, Lew Eric, and Suzanne, respectively. The children’s adoptions were the first phase of a larger Peoples Temple project that sought homes for orphaned children fathered by American servicemen stationed in Korea, an effort members financed through dinners and profits from the church’s restaurant and cleaning business.19

Just a year after the adoption, Stephanie died at the age of five in a car crash along with four other members of Peoples Temple on the way home from a church trip to Cincinnati. Stephanie’s death prompted the question of where members of Peoples Temple, as an extended interracial family, would or could be buried during a time when cemeteries in Indianapolis, like much of the United States, remained racially segregated. Funeral directors in the city denied Stephanie burial in the white section of the cemetery because of her Asian race. The headline “Segregation Pursues Crash Victims into Grave” announced the decision on the front page of The Indianapolis Recorder, the city’s African-American newspaper.20 In response to the funeral director’s decision, Jones commented, “I decided to stay with my people, and arranged to bury her in a ‘colored’ location.” Jones’s reference to “my people” referred to all Blacks and people of color, a statement meant to both show loyalty to his Black-majority church community and his attendant disdain for racist segregationist White culture. More than a decade later, Jones would reference Stephanie’s burial in a waterlogged area of the segregated section of the cemetery in his sermons, an interment that reflected the larger structures of racism that subverted the lives of nonwhite children. Her gravestone was inscribed with “Our Korean Daughter,” a dedication that set Stephanie’s adoption by white parents in stone.21

Three weeks after Stephanie’s death, the Jones’s only biological child, Stephan, was born, his name a tribute to Stephanie’s memory.22 A year later, Jim and Marceline expanded their rainbow family further by adopting a Black child whom they renamed James Warren Jones Jr., or Jim Jr. for short, a choice that boldly signaled the couple’s pride in their non-white child.23 In doing so, Jim and Marceline Jones reportedly became the first white couple in the state of Indiana to adopt a Black child. Jim Jr.’s adoption was intended as a public challenge to a racist system that denied parental love and care to children on the basis of race. The couple’s decision to raise a Black son became a milestone regularly referenced by Peoples Temple members and sympathizers to symbolize Jim and Marceline’s heartfelt conquering of racism. To their followers in Indianapolis, the Jones’s rainbow family was the living metaphor of their dedication to dismantling racism. To critics, the public multiracial family signaled Jones’s status as a dangerous maverick who subverted America’s racial caste system.

Jones’s communal vision for Peoples Temple was modeled on his immediate rainbow family, with Jones as Father and Marceline as Mother. This living paradigm of extended interracial familiarity was displayed on the front page of The Indianapolis Recorder in April 1961, with a photograph captioned “Human Family.” The image shows Jim and Marceline reading a story out loud to their children, who are gathered around them staring intently at the pages. Jones had recently been appointed as director of the city’s Commission on Human Rights, and the photo’s caption – “he has a good sampling of the human family at home . . . with their international, interracial family” – suggested that his new political duties were a natural extension of his fatherly position.24 Nearly three years later, the same photograph of the family reading together was published to highlight the injustices Jones faced as a civil rights activist in Indianapolis. During his tenure as the director of Indianapolis’s Human Rights Commission, Jones faced backlash from the city’s white residents for forcing the integration of the city’s hospital wards. His integration of Peoples Temple’s church services similarly incensed many neighbors.

Peoples Temple and Jones’s challenges to Jim Crow in Indianapolis were meted out on the Jones family. While waiting for the bus one day, a middle-aged white woman walked up to Marceline and spit on her while she was holding Jim Jr. As Marceline began to cry, the woman spat on Jim Jr. out of apparent disgust at the sight of a white woman holding a Black child and the presumption of miscegenation. Not long after, an anonymous phone call to the Joneses’ housekeeper threatened the safety of the Jones children if they continued to visit the neighborhood playground. “Lay off civil rights,” said the voice. Another critic of the Joneses’ race politics was more blunt with their phone message: “Nigger lover get out of town.”25 In 1965, Jones moved along with around 140 followers to “greener and safer pastures” in Northern California.26 The children went with them.

Noah’s Ark in a Time of Storm

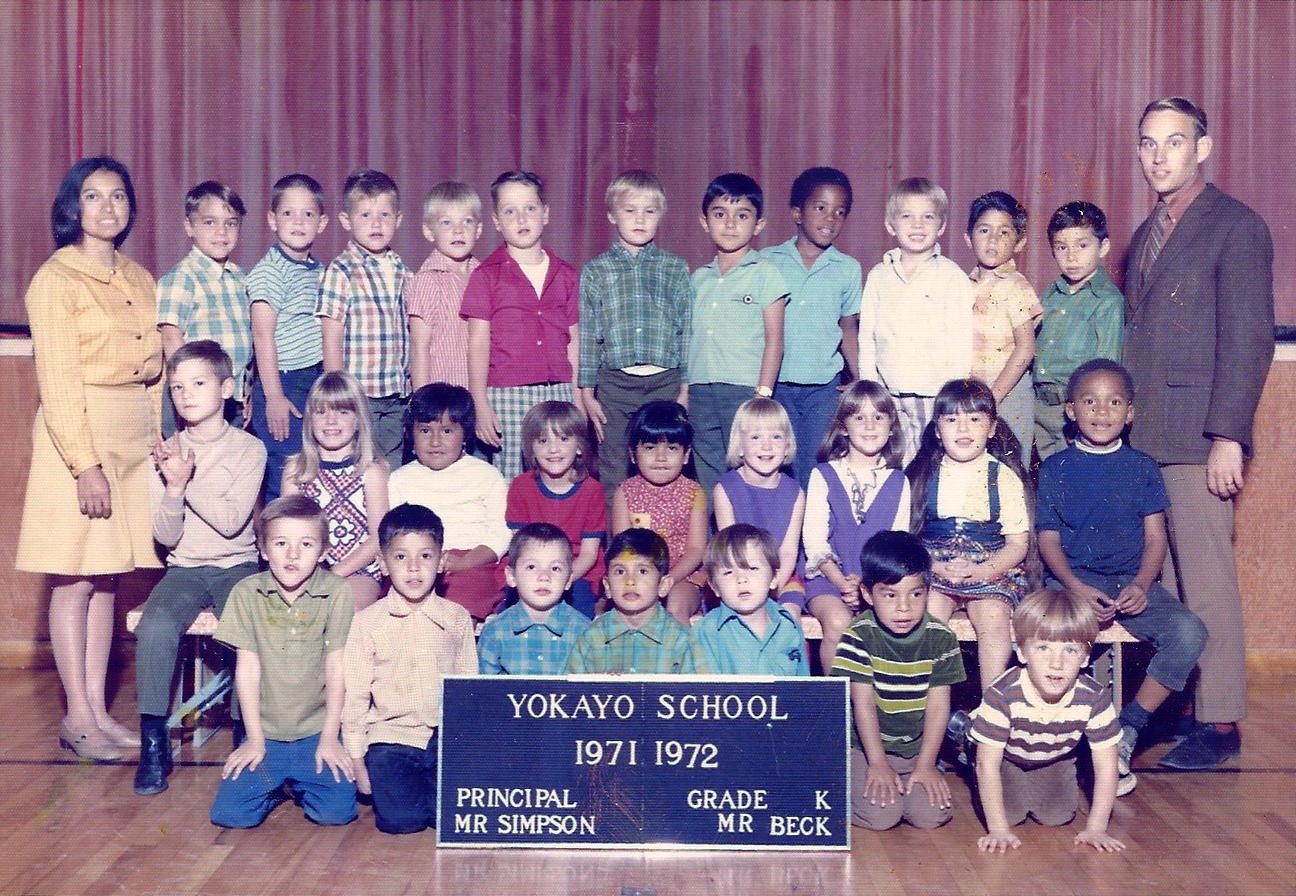

“One of things that first impressed me when I joined Peoples Temple in 1970 was its children. They were outgoing and open, eager and curious,” wrote Don Beck in 2013.27 Beck knew many of the Peoples Temple children well, having served as the group’s junior choir director and as a kindergarten teacher. Peoples Temple’s move to Redwood Valley offered the community a fresh start to realize its vision of an interracial and self-sufficient socialist society. A core component of this utopian ideal was the welfare of children. Redwood Valley was a white-majority area that Jones once remarked would be more aptly named “Whitewood Valley,” but the Peoples Temple settlement distinguished itself from the larger area by establishing what it saw as “the only Garden of Eden in America.”28 In this Eden, children of all races were educated in the Temple’s Sunday School, an instructive period that, despite its name, tended to take place on Monday or Wednesday evenings and could include choir practice, music lessons, and assistance with homework.29 Under Marceline Jones’s direction, the Temple established nine senior citizen homes, six homes for foster children, and “Happy Acres,” a forty-acre ranch for intellectually disabled children.30

In California, Jones built on his tradition of making church accessible and appealing to the youth.31 With Father Jones’s permission, the children were exempted from formal attendance at Sunday services and permitted to play outside, go horseback riding, or swim in the Temple’s large indoor heated pool, a facility that was housed in the church building and took up half its footprint.32 “Children of every race are invited to ride the ponies and swim in the indoor heated pool,” advertised the Peoples Temple newsletter from October 1970.33 The pool became a focal point of the Peoples Temple Redwood Valley complex, which opened on February 2, 1969, and served as a place for swimming, recreation, and baptisms.34 “The young people liked the fact that Jim Jones had a swimming pool in the sanctuary in Redwood Valley,” wrote Jynona M. Norwood, a Black pastor who lost many relatives at Jonestown. “People would peel their clothes off, put their bathing suits on, and jump in the pool right after morning worship.”35 At a time when Black adults and children continued to be barred from public pools and recreational facilities across the country, Peoples Temple’s public promotion of its integrated swimming pool in a segregated white rural area was an important way to signal its commitment to racial equality and firmly stake its position on another front of the culture war over racial integration.36

Religious Studies scholar Susan Ridgley has reminded researchers of child-centered studies that we “must always contend with the fact that children are simultaneously theoretical and actual beings, both current participants in religious life and placeholders for the future of communities.”37 Within Peoples Temple, this dynamic was transformed into social, spiritual, and economic capital. Children’s welfare was routinely abstracted as the righteous cornerstone of Peoples Temple’s interracial socialist vision for society and the attendant need for members’ dedication. The vision for and experiences of children were upheld as testimony to Peoples Temple’s integrity, and collectively the two functioned as moral signposts to undergird multiple functions: maintain members, attract new members, solicit donations, and justify the dedication of members as well as the actions of Peoples Temple leadership.

Beginning in Redwood Valley, children were increasingly the focus of media, both in publications authored by Peoples Temple and those in which Peoples Temple was referenced. Peoples Temple member Laura Johnston Kohl recalled that “pictures of Jim and his family – both primary and extended – were all around.”38 Photos of the family were included in contribution appeal letters and sold at church meetings. The community emphasis on interracial families and child welfare was further advertised throughout Peoples Temple’s The Living Word magazine, the group’s first serial publication, printed in 1970, which reads in part: “Following the example of our Pastor and his wife, Marceline, who have adopted and reared eight children of all races, our families have taken children into their hearts and homes as though they were their own. Many have opened up foster homes especially to meet the needs of these displaced young ones.”39 An editorial titled “Brotherhood is Our Religion” depicted Redwood Valley as a paradise: “From all corners of the country and even from many foreign lands, men, women, and children of all ages, races and social classes are coming to this Promised Land of Milk and Honey, this Noah’s Ark in atime of storm.”40

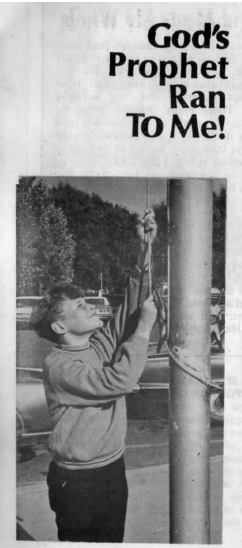

The editor of The Living Word was Garrett Lambrev, the Peoples Temple’s first recruit in California and later a defector and vocal critic of the group. In 2013, Lambrev reflected on his participation in putting together The Living Word and derided the publication as “garbage” meant purely to seduce readers into giving funds to the church.41 The Living Word included only one testimony by a young person – an article titled “God’s Prophet Ran to Me” by twelve-year-old Mark Cordell. “If I hadn’t been touched by the anointed hands of our Pastor, Jim Jones, I would be hopelessly crippled from the waist down,” read Cordell’s testimony. “Without him [Jones], I’d have to spend the rest of my life in a wheelchair, unable to run and play like other children.” According to Lambrev, Mark Cordell’s story was real, but the published version was carefully crafted by Lambrev and the rest of the editorial staff. Cordell’s story may have been true, but his experience at Peoples Temple was not the idyllic version painted by the Peoples Temple magazine. Peter Wotherspoon, The Living Word’s assistant editor, was later charged with sexually abusing Mark Cordell. In a community predicated on the safety and well-being of children, physical and sexual abuse of Peoples Temple children was met with harsh physical punishment. The nature of the community’s punishment of Wotherspoon was enough to prompt Lambrev to leave Peoples Temple for good.

Stephan Jones, in a 2018 interview with ABC about his life growing up in Peoples Temple and the ambiguities of his father’s character, commented, “I lived in a community that was filled with every walk of life, every color in the rainbow, every level of education. For the most part, we lived in harmony most of the time, especially early on. It was not fake.”42 Life as a child or young person at Peoples Temple cannot be represented by any single voice, and the loss of so many youth at Jonestown forever erased hundreds of unique perspectives. Moreover, adult recollections of youth are not substitutions for child and youth perspectives and cannot be considered adequate stand-ins. Despite these limitations, recollections about Peoples Temple children and youth, and former members’ experiences growing up in the community, can offer some glimpses into the environment the children and youth were raised in and experienced.

In “Remembrances of Temple Kindergarteners,” Don Beck profiled five young members of Peoples Temple he taught in a Redwood Valley and Ukiah, California public school. The first was Martin Amos, who would later die in Guyana at the hands of his mother, Sharon Amos.43 Beck recalled Martin as a “very independent, engaging and strong-willed kid. Never the shy type . . . almost always smart enough to make it happen.” Stephanie Swaney was “shy and quiet . . . a very normal kid.” Chris Buckley had an “awesome smile. Good humor. Loved to play: always eager to move around and help me and others do things . . . always learned quickly and worked well with others.” Jimmy Moore was “a great kid, very eager to do things and help. Always good-natured. Loved responsibilities that let him move about.” The last child profiled was Daren Werner Swinney. For Beck, Daren was “like many of our kids.” He continued: “They [the children] needed more of our attention, consistently. Unfortunately we were often too busy to give the extra attention our kids needed. In many ways the activities we provided our kids, opened up much energy that we then couldn’t seem to work with enough – this was one reason we wanted to build a community – a place – where we could do more things more effectively with our children.”44 The tension Beck points to between the community’s vision for children and its practical limitations is underwritten with the grief surrounding the children’s deaths in Jonestown.

Children Are Not Dolls. They Are Our Future.

In November 1976, Julie Cordell held a three-year-old Black child up to the microphone in front of the Temple audience in San Francisco. The child sang the civil rights anthem “We Shall Overcome” in both English and Spanish. Children were active participants in Peoples Temple programs and church services, often to the chagrin of adult members who complained the children were too noisy or disruptive. A journal kept by Temple member and former college professor Edith Roller offers snapshots of children’s presence and participation in Peoples Temple from 1975, when she joined at the age of sixty, until August 1978, just a few months before her death in Jonestown.45 Among Roller’s entries during the period were accounts of church meetings and Jones’s sermons held in San Francisco. Services had been held in San Francisco since 1970, and in 1972 the group established a Temple on Geary Street. The building’s original pews were replaced with chairs that could be easily moved to make room for dancing and Temple functions. Jones and Peoples Temple members became deeply immersed in San Francisco politics and protest movements. In turn, the community became widely known for their outreach to neighbors and the social services they organized, including a dining hall, daycare, diagnostic and outpatient clinic, physical therapy facility, drug rehabilitation program, and legal services, all offered at no cost.46

In 1976, visitors to the Geary Street Temple observed the social dynamic of the Temple environment: “young and old, black and white – everyone interspersed. . . . Black children sat on the laps of white men or women, white teenagers sat next to elderly black people.”47 Children figured prominently in the church meetings, which were dual-purposed gatherings that served both spiritual and practical organizing needs for a community of around a thousand people. Children, even very young children, stood up to give testimonies. In large groups, they regularly sang songs, often in different languages, including “I Thank You, Jim,” “I’m a Socialist,” and “We Shall Not Be Moved.”48 Children were included in all variety of Temple business and announcements, from practical mentions about their need to continue pamphleteering and distributing Temple newspapers, to announcements about trips to Marineland, to commendations for good grades.49 Their bad behavior was met with punishment during accountability sessions called “catharsis,” where they were struck by a paddle in front of the entire community or assigned penance. Stealing, for example, was punished with having to raise money. Rudeness to seniors required service to older persons.50

Messages about proper conduct were communicated to members during services. On January 26, 1977, Marceline relayed guidance from Father, or Jim Jones, to the children: “Be good to your teachers. Be helpful and cooperative. Set an example of socialism. Treat each other kindly.”51 Adults were reminded to treat Temple children well, and those who didn’t were publicly admonished. “Some of you play with children like stupid dolls,” chastised Jones in December 1976. “Children are not dolls. They are our future.”52 Roller’s notes on Jones’s sermons include his regular undergirding of children’s welfare. On September 29, 1976, Roller recorded, “Jim talked about the care of children.” She summarized his sermon:

We’ve inherited children who’ve been beaten, neglected. If we sacrifice our children we may as well cast ourselves into the sea. If you don’t love children, you don’t understand socialism. You are not in my spirit. Don’t scream at them, but talk to them. There have to be rules but be sure that those rules have a foundation in love. Don’t take out the hostility with which you were treated on them . . . Don’t use corporal punishment of children without involvement of the office. Be inventive to find other means of discipline. Violence can’t teach people to be non-violent.53

Threats to child welfare were presented as both internal and external. References to external threats facing children included lead poisoning, child labor, pollution, inferior schooling, physical abuse, and forced prostitution. “A child is being beaten every minute. Child abuse is the commonest crime,” sermonized Jones.54 He depicted America as a country with more racist oppression and child abuse than every other country combined.55 Insufficient nutrition was similarly identified as a growing social scourge causing undue harm to children, one that Marceline chose to highlight in 1976. She discussed “The Unfinished Child,” a public service documentary that had recently aired on ABC. The program sought to raise attention to the need for proper prenatal and infant nutrition to avoid developmental disabilities.56 In response, Marceline called for the community’s nurses to develop healthy menus for the communal homes where many of the young people lived. “Our young people will be physically prepared to replenish the earth,” Marceline declared.57

Father Jim and Mother Marceline’s ongoing directives to members to thoughtfully care for children were premised in the community’s conception of the Temple as an extended family unit. This principle of a communal family stretching beyond racial and biological lines was reinforced by the extended kinship networks that knit many members together.58 It was not uncommon for entire families to join the Temple en masse. Further cementing the extended familial bonds between Temple members was the relocation of individuals members from one Temple location to live with a family at another location, or the boarding of individual youth members or foster children with established families. As a result, single mothers, otherwise-isolated seniors, and children and youth without parents enjoyed the benefits of a robust and interconnected family dynamic.59 This entrenchment of bonds across and beyond race and nuclear family lines was “the practical application of the principles Jim espoused,” the socialist rainbow family of Peoples Temple that radiated outward from his own family at the center.60 Within this layered breakdown of the traditional family unit, all children were the community’s children. Their welfare was upheld as both a living testament of the Temple’s principles and a beacon of the future society the Temple was building.

Now We Must Work to Save Our Children

Apocalypticism had been a constant theme in Jones’s ministry from the beginning and steadily increased throughout Peoples Temple’s development. Jones’s sermons regularly inculcated members with a view of America as a fundamentally racist country on the verge of nuclear catastrophe. In the 1960s, Jones’s convictions were reinforced by media coverage of urban riots that revealed the extent of police violence against Black Americans and the government’s extensive surveillance of Black radicals such as the Black Panthers.61 As early as 1972, Jones cited the King Alfred Plan, a set of fictional government documents then making the rounds of radical publications. The documents alleged that a fascist military dictatorship would soon take power in America, leading to the creation of concentration camps for Black people and the working class.62 “The important thing now is survival. We’ll have time later for travel, now we must work. We’re facing genocide. Now we must work to save our children,” Roller’s journal recorded in 1976.63

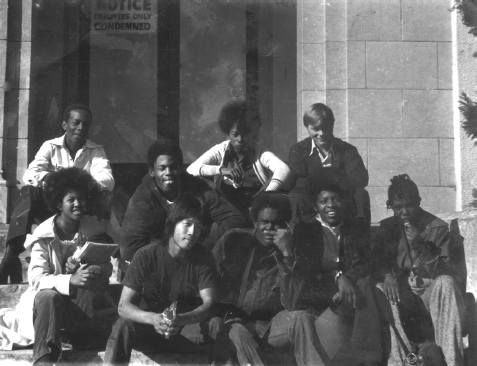

As a Black-majority socialist movement, Peoples Temple members saw themselves among the government’s primary targets in the pending fascist takeover. When Jordan Vilchez joined Peoples Temple at the age of twelve in the late 1960s, she was led to believe that “nuclear war was inevitable.” A “perpetual climate of fear, doom and gloom” characterized Vilchez’s years in Peoples Temple, a period that stretched until 1978, when she was twenty-one.64 In 1973, news of the military coup that overthrew democratically-elected socialist Chilean president Salvador Allende further bolstered Jones’s belief in a budding global conspiracy to subvert socialism. Vilchez was taught that the same violent fate dealt to Allende and his family awaited the Peoples Temple family. In San Francisco, her blue choir dress from the Redwood Valley period was replaced with the black beret then characteristic of Black radicals, a look routinely complemented by revolutionary fist raising. Peoples Temple youth were primed for the imminent fascist attacks through regular vigilance and security drills. They were encouraged to relay important messages orally rather than risk their writing be intercepted.65 Peoples Temple’s camaraderie with the global struggle for revolutionary socialism was reinforced through screenings of footage from the Soviet Revolution of 1917, the Cuban Revolution of 1959, and films depicting threats to the left from right-wing nationalism. In addition, the youth were educated about socialist politics with reading lists that included Marx’s Das Kapital and histories about turn-of-the-century labor activists Joe Hill and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, a founder of the ACLU and leader of the Communist Party.66

Roller’s journal entries corroborate Vilchez’s recounting of the group’s regular inculcation of socialist values among the youth and children. At Temple services, children as well as adults were encouraged to ask questions in front of the community. Roller recorded several instances of children asking the meaning of political terminology, such as capitalism, left-wing, and right-wing. During the question-and-answer period on January 16, 1977, children asked the following questions with the answers provided by Jones:

Child: How did Martin Luther King die?

Answer: Because he was socialist and started to tell how the poor blacks were exploited in Vietnam, he was shot down.

Child: What is [the] Third World?

Answer: It’s us all black, brown, red and yellow people, and they’re going to take over the whole world.

Child: Why do capitalists kill black people?

Answer: Not just black people, all people because they are selfish. They’re mean.

Another exchange from the January 9, 1977 question-and-answer period reveals the threat the children and larger community believed they faced:

Child: Why do they want to kill [the] black liberation movement?

Answer: They know they owe us a debt. People avoid someone they owe. White America owes us 300 years of liberation. We make them feel guilty. They want us dead. We may go away but we’ll be back. People of color are going to rule the whole world. They’re afraid of black unity.67

The Opportunity Students

Among Peoples Temple’s multifaceted approaches to subverting racism and poverty was an ongoing dedication to uplifting teens and young adults. Beginning in Redwood Valley and expanding to San Francisco and Los Angeles, Peoples Temple offered opportunities for teen education, free college and housing, drug rehabilitation programs, and job training. Jones’s work to advance the youth earned him regular accolades from public officials and religious leaders and was cited regularly by the Temple to buttress the leader’s social standing. A 1976 press release from Peoples Temple read in part, “For the first time in their lives, a multitude of young blacks live with a sense of utter pride and dignity, because Rev. Jones has fought to provide them the opportunity to realize their goals.”68

In 1975, while in San Francisco, Jones enrolled 120 Peoples Temple youth at Opportunity II, a progressive high school founded on leftist values. The cohort of students were mostly Black, with some Asian, Native American, and white students. Among them were Jones’s sons Stephan, Tim Tipper, and Jim Jr.69 Two of the teachers recalled that the Peoples Temple students “carried themselves more like a family, sharing a closeness that reflected their lack of racism.” They arrived at Opportunity II with a profound awareness of socialist and labor history, and their consciousness about racial inequality in America was routinely demonstrated in their art.70 A poem by Willie Thomas, a Black teenager from Peoples Temple who attended the school, read in part:

Young, old, poor and black Shot,

burned, killed, beaten, For what

reason?Our dark skin?

Prejudice Please helpThey’re laying down a little black child . . . Who killed

that little boy?Somebody tell me Who

killed him?71

When the youth cohort attended Opportunity II, Jones was a local political celebrity, and Peoples Temple was widely known in San Francisco for its high-profile activism and community services. In response, Cindy Cordell authored an article for the school’s newspaper, The Natural High Express, which aimed to shed some light on Jones and Peoples Temple for her fellow classmates. She listed many of the activities the youth of Peoples Temple were then engaged with, including distributing the community’s newspaper, visiting people in the hospital, aiding seniors, helping in the Temple kitchen, and cleaning the Temple’s eleven buses often used for missionary travel.72 “The youth of Peoples Temple also stay away from any unnecessary drugs and completely away from smoking and alcoholic beverages,” Cordell noted.73

The pride the cohort had in their Temple community can also be seen in the cover Marty Emmons, a Native American teen member of the Temple, drew for In Small Dreams, the school’s poetry publication. The drawing shows Jones’s face, looking very like Superman’s, emerging from the center of a group of multiracial youth.74 One by one over the course of 1977, Peoples Temple students unenrolled from Opportunity High to move to Jonestown, the group’s agricultural settlement in Guyana. They left behind a vacancy of spirit the school never recovered from, a void that only deepened when news about troubles in Jonestown started to reach San Francisco.75

Battlegrounds

Jones’s regular citation of Peoples Temple as a safe haven for children and young people conflicted with several investigative journalist and defector accounts. In 1972, Episcopal priest, religion editor, and later conservative radio host Lester Kinsolving authored an eight-part exposé of Peoples Temple for the San Francisco Examiner. Kinsolving sought to reveal what he believed was Jones’s false theology and the church’s suspicious financing. Among four articles that went unpublished was “Sex, Socialism, and Child Torture with Rev. Jim Jones,” which alleged that Jones had forced a child to eat his own vomit.76 Kinsolving’s report appeared concurrently with another exposé by Indianapolis Star reporter Carolyn Pickering. Peoples Temple responded that both series of articles were a form of harassment and deliberate attempts to discredit the good work of Peoples Temple.77

Far more damaging was an article published in New West magazine in 1977, which called for an official investigation of Jones and was based on interviews with former members. Among the many offenses referenced in the article was the Temple’s routine corporal punishment. Elmer and Deanna Mertle reported that adults and children were regularly spanked up to one hundred times with a large paddle called “the board of education,” after which the offender would have to say “Thank you, Father” to Jones. Their daughter, Linda Mertle, was reportedly struck seventy-five times when she was sixteen for hugging and kissing a female friend. According to her faither, Elmer Mertle, “she was beaten so severely, that the kids said her butt looked like hamburger.”78 The authors of the New West article alleged they endured repeated intimidation tactics from Peoples Temple to prevent the article from being published. Despite this, the article appeared in the magazine’s August 1, 1977 edition. Even before its publication, the threat of negative media coverage had prompted asignificant migration or “mass exodus” of Peoples Temple members to Guyana, a forced relocation interpreted by Temple members as further evidence of their persecution in America. “The power of right-wing media chased us miles across this country and over the rough seas,” wrote Temple recording secretary B. Alethia Orsot. “They hounded, clamored, demanded, invaded, violated, discredited and destroyed us. They wouldn’t leave us alone to heal and try to enjoy the happiness we had earned.”79

To the Promised Land

On January 7, 1977, a child announced in front of the Temple that he wanted to go to the “promised land,” the community’s name for the agricultural settlement in Jonestown, Guyana. “That’s a smart kid, what the black people need,” responded Jones.80 From 1972 to 1977, Peoples Temple had grown from a community of a couple hundred followers to several thousand spread over three California locations – Ukiah (and Redwood Valley), Los Angeles, and San Francisco.81 Convincing Temple members to move to a new country thousands of miles away took work. “He [Jones] promised that our kids would never be prostitutes again, or never be hooked on drugs, and would never drop out of school,” explained Jynona Norwood. “That’s why my loved ones and relatives went to Jonestown. It was for the cause.”82 Jones told Norwood’s aunt: “If you bring your children out of America, I will make your children great and they will have a place where they will not have to be in slavery to the white man any more. That was the reason his congregation stayed with him: they shared Dr. King’s dream for a better life, for the paradise of equal rights.”83 As Norwood highlights, Jones leveraged child welfare to argue for Temple members’ migration to Guyana. Jonestown survivor Laura Johnston Kohl corroborated this view: “When discussion about Guyana first came up, Jim spoke about constructing a Promised Land, a safe place for our children and for our community. His persuasive speeches and enthusiasm broke down even the fiercest opposition.”84 Those who moved to Jonestown were likened to refugees who were fleeing persecution. “Parents wanted their children to live in a just and healthy community, away from violence and drugs,” Kohl added. “People wanted to participate in a rainbow family, an adoptive family, where all races and backgrounds were welcomed.” Once they arrived in Jonestown, they could not easily leave.85 The intricate and extended familial connections within Peoples Temple added to the difficulty of separation.

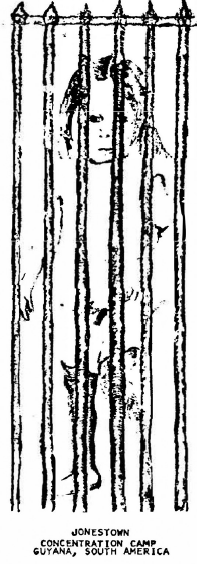

One of the people interviewed for the New West article was Grace Stoen, a former Peoples Temple leader turned ardent critic. Stoen was embroiled in a legal struggle to gain custody of her five-year-old son John Victor, aka John-John, whose care she had entrusted to Peoples Temple members. Stoen worked with her estranged husband, Timothy Stoen, also a former leader of Peoples Temple, to recover the child from Jonestown. Despite the Stoens’ claims, Jones insisted John Victor was his biological son rather than Timothy’s.86 The Stoens’ case was just one among several custody battles that became increasingly heated as more children and relatives relocated to the Promise Land. Concerns were amplified through the efforts of the Concerned Relatives, a group of parents, relatives, and former members of Peoples Temple who sought redress for custody battles and property disputes as well as access to relatives they believed were mistreated in Jonestown. The group petitioned US government officials and sought support in the court of public opinion to force Jones to release children and others living in Jonestown. A flyer distributed by the Concerned Relatives depicted Jonestown as a forced labor camp where adults and children were being held against their will. Included in the flyer was a drawing of a child that appealed to readers from behind the bars of the “Jonestown concentration camp.”87

Despite the Stoens’ and Concerned Relatives’ efforts, the US government was limited in its power to enforce custody claims in Guyana. According to Richard A. Dwyer, the deputy chief of mission at the American Embassy in Guyana during the Jonestown period, the children under question were all either of legal age or had legal guardians present at Jonestown.88 In a cruel twist of irony, the Stoens’ custody battle, in combination with efforts by the Concerned Relatives to aid children, has been identified as one of the contributing factors that led to the mass murder and suicides that occurred in the wake of Congressman Leo Ryan’s visit to Jonestown in November 1978. On this point, sociologist of religion John R. Hall has observed that “the opponents’ own actions helped to precipitate a course of events that presumably led to the fulfillment of their own worst fears.”89 Custody battles and attempts by the Concerned Relatives to reclaim children through the Guyanese courts aggravated Jones’s and Peoples Temple leadership’s longheld conviction that the group was under siege from outside forces and that the safety of the community’s children was compromised. On one of the “White Night” suicide drills in Guyana, Laura Johnston Kohl recalled, “Jim yelled that ‘they’ were coming for our children. He generalized that either the Guyanese Defense Force, or American soldiers, or someone, was going to come into Jonestown and get the kids, and the suggestion was that the invaders would snatch all the children, not just the nine living there without proper authorization.”90

In September 1977, in what became known as the Six-Day Siege, the Stoens’ attorney Jeffrey Haas successfully appealed to the Guyana Supreme Court to issue a writ of habeas corpus to Jones regarding the legality of his custody claim of John Victor. Jonestown leaders interpreted the court order as a sign the community faced an imminent attack by the Guyana Defense Force and mounted an armed response, what Rebecca Moore has described as “a state of siege.”91 The Temple’s fear was that if one child was taken, it would open the floodgates, and all of the Temple’s children would be at risk. All members of Jonestown, including children, were armed with machetes, rakes, and farm implements and ordered to prepare for an attack. Jones attempted to leave Jonestown for Cuba on a boat with John Victor, but the Kaituma River was blocked.

During the siege, Angela Davis sent the following message to Jones: “I know you are in a very difficult situation right now and there is a conspiracy. A very profound conspiracy designed to destroy the contributions which you have made to our struggle. And this is why I must tell you that we feel that we are under attack as well.”92 The words lent credence to the Temple’s growing conviction that the community was on the frontlines of a battle. Barbara Walker, a Black woman from Los Angeles who had moved to Jonestown in 1977, left behind a poetic account of the siege that reflects this sense of threat. Walker’s poem reads in part:

Gave you your country, and got a land of our own.

We were freed from your shackles by our leader Jim Jones. When he gave us Jonestown, Guyana as our new-found home.

It was his desire to give his people a chance to be happy, a chance to be free

And to give our children the right to live free of the pain created by your capitalist society.

This is ours, we are here to stay, we’re committed to the socialist life, because it’s the only way

On my own land, proud and free. And nobody is going to take my freedom from me.

I’ve come here to learn to love, share and build. And if I can’t do this, I don’t want to live!93

Seven months after the siege, on April 11, 1978, the Concerned Relatives sent Jones their “Accusation of Human Rights Violations by Rev. James Warren Jones Against Our Children and Relatives at the Peoples Temple Jungle Encampment in Guyana, South America.” The document included a “Summary of Violations,” including Jones’s refusal to allow family members to see their children at Peoples Temple, and his declaration “that it is better even to die than to be constantly harassed from one continent to the next,” which threatened the lives of all members, but particularly those of the children.94 Former members and relatives have been adamant that within the debate over whether November 18, 1978, was a mass suicide or a mass murder, there is no question that the infants and children were murdered. Jynona Norwood, who has stated her family lost twenty-seven members at Jonestown, explains: “They’ve tried to tell us I twas suicide. But a three-week-old baby does not commit suicide. When an adult gives a child poison, that is not suicide.”95 Despite her profound loss and ongoing criticism of Jones, Norwood recalls the larger purpose of Peoples Temple with compassion: “The people of Peoples Temple were not selfish, crazy people. They were compassionate people who loved their children so much that they traveled to a strange land, carved a community out of the jungle with their own blood, sweat and tears, and did so in an effort to get their families away from a life of drugs, jail, discrimination, poverty and unhappiness.”96

Conclusion

“They started with the babies,” recalled Odell Rhodes.97 Rhodes was one of fewer than a handful of surviving members to have witnessed the events of the night of November 18, 1978. A Black man, Rhodes credited Peoples Temple with saving him from a life of addiction. He was remembered as a mentor among Peoples Temple youth. Details of the mass murders and suicides he witnessed were reported in newspapers around the country. Among them were descriptions of children being force-fed poison. “It just got all out of order,” recalled Rhodes. “Babies were screaming, children were screaming and there was mass confusion.”98

In an undated memo found at Jonestown, Annie Moore, one of the community’s nurses, wrote, “The main reason for suicide – to assure safety to the children.”99 Moore’s conclusion reflected a larger Temple position, routinely impressed by Jones, that taking the lives of the children was superior to letting them be brainwashed, tortured, or murdered by fascist enemies. Moore’s note reveals an internal struggle about the pending act of “revolutionary suicide,” a recognition of the cruel irony that liberation and death could be so closely entwined. Rather than surrender John Victor, or any of the children, Jones and the leadership prepared the community for death. The decision, long rehearsed, was framed as an act of heroism akin to the Jews at Masada.100 When the night came, only Christine Miller’s voice countered Jones’s call for “revolutionary suicide.” She appealed to the group on account of the children. “But I look at all the babies and I think they deserve to live,” argued Miller. Jones dismissed her reasoning and replied, “But don’t they deserve much more? They deserve peace. . . . When they start parachuting out of the air, they’ll shoot some of our innocent babies. Can you let them take your child?” A wave of shouting voices from the crowd erupted in response: “No! No! No!”101

Notes

[1] I extend my sincere gratitude to Rebecca Moore for her thoughtful feedback on this chapter.

[2] Precise membership numbers are difficult to ascertain due to the geographic scope of the community and differing assessments of who counted as members. Mary R. Sawyer has offered a range of around 2,000 to 3,000 active members for the period in San Francisco, 1971–1978. Mary Sawyer, “The Church in People’s Temple,” in Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, ed. Rebecca Moore, Anthony Pinn, and Mary R. Sawyer (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004), 169.

[3] “How Many Children and Minors Died in Jonestown? What Were Their Ages?,” The Jonestown Institute, September 29, 2013, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=35332.

[4] Depending on the period and place of consideration, African Americans represented between 80% and 90% of Peoples Temple Sawyer, “The Church in People’s Temple,” 169.

[5] Hugh Urban, “Peoples Temple: Mass Murder-Suicide, the Media, and the ‘Cult’ Label,” in New Age, Neopagan, and New Religious Movements: Alternative Spirituality in Contemporary America, ed. Hugh B. Urban (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2015), 245.

[6] Lowell Streiker, “Reflections on the Human Freedom Center,” in The Need for a Second Look at Jonestown: Remembering Its People, ed. Rebecca Moore and Fielding M. McGehee (Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellen Press: 1989), 161.

[7] See Rebecca Moore, Anthony Pinn, and Mary R. Sawyer, eds., Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America (Bloomington: Indiana UniversityPress, 2004); James Lance Taylor, “Bring Out The ‘Black Dimensions’ of Peoples Temple,” The Jonestown Institute, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=29462; Sikivu Hutchinson, “Black Women and the Peoples Temple in Jonestown,” Black Perspectives, January 31, 2017, https://www.aaihs.org/black-women-and-the-peoples-temple-in-jonestown; Sikivu Hutchinson, White Nights Black Paradise: A Novel, (Los Angeles, CA: Infidel Books, 2015); Mary McCormick Maaga, “The Triple Erasure of Women in the Leadership of Peoples Temple,” in Hearing the Voices of Jonestown: Putting a Human Face on an American Tragedy (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1998).

[8] Sawyer, “The Church in People’s Temple,” 170.

[9] “How Many Children and Minors Died in Jonestown? What Were Their Ages?,” The Jonestown Institute, September 29, 2013, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=35332.

[10] Don Lattin, a reporter for the San Francisco Examiner at the time of the tragedy, uncovered how some of the youth of Jonestown were sent there in lieu of juvenile hall through efforts made by Temple members working at county social service. Don Lattin, “Children of Jonestown and the Children of God,” The Jonestown Institute, February 17, 2014, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=31412.

[11] On the limited frameworks used to analyze children within NRMs, see Charlotte E. Hardman, “Children in New Religious Movements,” in The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements, James R. Lewis (Oxford: Oxford Handbooks, 2008).

[12] Maaga, Hearing the Voices of Jonestown, 39.

[13] Kenneth Wooden’s The Children of Jonestown (1981) is perhaps the best example of a singular focus on child abuse within Peoples Temple.

[14] Don S. Browning and Bonnie J. Miller-McLemore, eds., Children and Childhood in American Religions, (Piscataway: Rutgers University Press, 2009), 12.

[15] Browning and Miller-McLemore.

[16] A large portion of the remembrances by former members and relatives as well as primary source material for this chapter is drawn from Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple, an online archive of materials relating to Peoples Temple, sponsored by the Special Collections of Library and Information Access at San Diego State University. The collection is cited as The Jonestown Institute.

[17] “Peoples Temple Newsletter, August 1970,” The Jonestown Institute, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=14095.

[18] Robert Spencer, “My Mother, Agnes Jones,” https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=61624.

[19] “Korean Waifs’ Adoption Called ‘Lesson’ in Religion,” Indianapolis News, February 25, 1960.

[20] “Can’t Find Integrated Burial Place for Child,” Indianapolis Recorder, May 16, 1959.

[21] “Stephanie Jones,” Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/31289300/stephanie-jones.

[22] Rebecca Moore, Peoples Temple and Jonestown in the Twenty-First Century, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2022), 12.

[23] That same year, the Jones also adopted Timothy Glenn Tupper (often shortened to Tim or Timmy), whose birth mother, Rita Tupper, was a Temple member.

[24] “Human Family,” The Indianapolis Recorder, April 1, 1961.

[25] Pat Williams Stewart, “White Liberal Suffers Abuse From ‘Both Sides’; Still Struggles On,” The Indianapolis Recorder, July 25, 1961.

[26] Moore, Peoples Temple and Jonestown, 12.

[27] Don Beck, “Confessions of a Junior Choir Director,” July 24, 2021, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=30782.

[28] David Chidester, Salvation and Suicide: Jim Jones, the Peoples Temple, and Jonestown, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991), 6.

[29] Beck, “Confessions of a Junior Choir Director.”

[30] Moore, Peoples Temple and Jonestown, 48.

[31] Jeff Guinn, The Road to Jonestown: Jim Jones and Peoples Temple (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017), 83.

[32] “Peoples Temple Christian Church, Jim Jones, Pastor,” The George Moscone Collection, University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons, 1976, https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/mayor-moscone/3.

[33] “Peoples Temple Newsletter, October 1970,” The Jonestown Institute, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=14096.

[34] Lawrence Wright, “Orphans of Jonestown,” The New Yorker, November 22, 1993, 68.

[35] Jynona M. Norwood, “We Cannot Forget Our Own,” in The Need for a Second Look at Jonestown: Remembering Its People,ed. Rebecca Moore and Fielding M. McGehee (Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellen Press: 1989), 175.

[36] On the history of segregation and recreation, see Victoria Wolcott, Race, Riots, and Roller Coasters: The Struggle Over Segregated Recreation in America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012).

[37] Susan Ridgely, “Children and Religion,” Religion Compass 6, 4 (2012): 239.

[38] Laura Johnston Kohl, “Change and the Chameleon That Was Jim Jones,” The Jonestown Institute, November 20, 2019, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=70623.

[39] Garrett Lambrev, “Brotherhood Is Our Religion,” in The Living Word: An Apostolic Monthly 1, no. 1 (July 1972): 33, The Jonestown Institute, https://sdsu.edu/?page_id=14091.

[40] Lambrev, “Brotherhood Is Our Religion.”

[41] Garrett Lambrev, “The Living Word and Me: The Limits of Anarchism in Peoples Temple,” The Jonestown Institute, June 17, 2018, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=32374.

[42] Alexa Valiente, “40 Years after the Jonestown Massacre: Jim Jones’ Surviving Sons on What They Think of Their Father, the Peoples Temple Today,” September 28, 2018, ABC News, https://abcnews.go.com/US/40-years-jonestown-massacre-jim-jones-surviving-sons/story?id=57997006.

[43] Joseph B. Treaster, “A Cult Mother Led Children to Death,” The New York Times, December 5, 1978, 35.

[44] Don Beck, “Remembrances of Temple Kindergarteners,” July 24, 2021, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=29249.

[45] It is possible Edith Roller kept a journal longer, but the pages have not been recovered.

[46] Marshall Kilduff and Phil Tracy, “Inside Peoples Temple” New West, August 1, 1977, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=14025.

[47] Judy Bebelaar and Ron Cabral, And Then They Were Gone: Teenagers of Peoples Temple from High School to Jonestown (Berkeley: Minuteman Press, 2018), 69.

[48] Edith Roller, “Edith Roller Journals: January 1977,” October 20, 2021, The Jonestown Institute, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=35686.

[49] Edith Roller, “Edith Roller Journals: August 1976,” February 24, 2022, The Jonestown Institute, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=35681.

[50] Moore, Peoples Temple and Jonestown, 35.

[51] Edith Roller, “Edith Roller Journals: January 1977.”

[52] Edith Roller, “Edith Roller Journals: December 1976,” December 26, 2021, The Jonestown Institute, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=35685.

[53] Edith Roller, “Edith Roller Journals: September 1976,” February 24, 2022, The Jonestown Institute, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=35682.

[54] Edith Roller, “Edith Roller Journals: May 1976,” December 30, 2020, The Jonestown Institute, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=35678.

[55] Edith Roller, “Edith Roller Journals: November 1976,” October 22, 2021, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=35684.

[56] Les Brown, “TV: Formula Maker Paid for ABC Film on Infants,” The New York Times, June 9, 1976, 56.

[57] Edith Roller, “Edith Roller Journals: June 1976,” transcribed by Don Beck, August 2009, The Jonestown Institute, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=35679.

[58] For a detailed understanding of the expanded kinship connections between Peoples Temple members, see “The Family Trees of Jonestown,” The Jonestown Institute, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=35705.

[59] Milmon Harrison, “Jim Jones and Black Worship Traditions,” in Peoples Temple & Black Religion in America, 128.

[60] Laura Johnston Kohl, “Migration and Emigration,” The Jonestown Institute, November 20, 2019, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=81226.

[61] Merve Emre, “How a Fictional Racist Plot Made the Headlines and Revealed an American Truth,” The New Yorker, December 31, 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/books/second-read/how-a-fictional-racist-plot-made-the-headlines-and-revealed-an-american-truth.

[62] “Two Sermons,” Q1059-2 Transcript, June 19, 1972, The Jonestown Institute, February 18, 2016, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=27332.

[63] Edith Roller, “Edith Roller Journals: July 1976,” December 30, 2020, The Jonestown Institute, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=35680.

[64] Jordan Vilchez, “Insight and Compassion: Vestiges of Peoples Temple,” March 4, 2014, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=33208.

[65] Vilchez.

[66] Vilchez.

[67] Edith Roller, “Edith Roller Journals: January 1977.”

[68] “Public relations release (September 26, 1976),” “Social Ministry for Social Justice,” California Historical Society, MS 3800, The Jonestown Institute, https://sdsu.edu/?page_id=18711.

[69] Bebelaar and Cabral, 35.

[70] Bebelaar and Cabral, 39.

[71] Bebelaar and Cabral, 51.

[72] Bebelaar and Cabral, 115.

[73] Bebelaar and Cabral, 117.

[74] Bebelaar and Cabral, 45.

[75] Bebelaar and Cabral, 139.

[76] Lester Kinsolving, “Sex, Socialism, and Child Torture with Rev. Jim Jones,” September 1972, The Jonestown Institute, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=14089.

[77] “The Temple Response to Carolyn Pickering,” The Jonestown Institute, December 31, 2019, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=18809.

[78] Marshall Kilduff and Phil Tracy.

[79] B. Alethia Orsot, “Together We Stood, Divided We Fell,” in The Need for a Second Look at Jonestown: Remembering its People, Rebecca Moore and Fielding M. McGehee (Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellen Press: 1989), 103.

[80] Edith Roller, “Edith Roller Journals: January 1977.”

[81] Tanya Hollis, “Peoples Temple and Housing Politics in San Francisco,” in Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, 96. Mary McCormick Maaga has demonstrated that there were three distinct groups within Peoples Temple: white and Black families from Indiana, younger white members from California, and urban Blacks who joined from San Francisco and Los Angeles. Maaga, Hearing the Voices of Jonestown, 75.

[82] Norwood, “We Cannot Forget Our Own,” 171.

[83] Norwood.

[84] Kohl, “Change and the Chameleon That Was Jim Jones.”

[85] Jennie Rothenberg Gritz, “Drinking the Kool-Aid: A Survivor Remembers Jim Jones,” The Atlantic, November 18, 2011, https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2011/11/drinking-the-kool-aid-a-survivor-remembers-jim-jones/248723/.

[86] Moore, Peoples Temple and Jonestown, 40.

[87] “Concerned Relatives Flyer,” “This Nightmare Is Taking Place Right Now,” The Jonestown Institute, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/ConRelflyer.pdf”>pdf.

[88] Richard A. Dwyer, interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy, The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project, July 12, 1990, 94, The Jonestown Institute, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Dwyer-Richard-A.toc_.pdf.

[89] John R. Hall, Philip D. Schuyler, with Sylvaine Trinh, Apocalypse Observed: Religious Movements and Violence in North America, Europe, and Japan (London: Routledge, 2000), 42.

[90] Laura Johnston Kohl, “Guyana 40 Years Later,” The Jonestown Institute, November 20, 2019, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=81250.

[91] Rebecca Moore, Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple (Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2009), 76.

[92] “Statement of Angela Davis to Jim Jones over Radio Phone-Patch,” September 10, 1977, The Jonestown Institute, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=19027.

[93] Barbara Walker, “The Front Line,” December 1977, The Jonestown Institute, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=13071. Barbara Walker died on the night of November 18, 1978, with her three children.

[94] “Accusation of Human Rights Violations by James Warren Jones Against Our Children and Relatives at the Peoples Temple Jungle Encampment in Guyana, South America,” April 11, 1978, The Jonestown Institute, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=13081.

[95] Professor of Psychology Katherine Hill has not been able to account for each member of the “Norwood 27,” despite efforts. The number is a potential sign of the extended family networks characteristic of Peoples Temple, in which non-biological relatives were routinely considered family. Katherine Hill, “In Search of the Norwood 27,” The Jonestown Institute, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=40218; Norwood, “We Cannot Forget Our Own,” 178.

[96] Norwood, 178.

[97] Charles Krause, “Survivor: ‘They Started with the Babies,’ ” The Washington Post, November 21, 1978.

[98] Charles Krause, “Gunmen Prevented Escapes,” Los Angeles Times, November 21, 1978, 1.

[99] Annie Moore, “Memo from Annie Moore,” The Jonestown Institute, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=78448.

[100] Guinn, 311.

[101] “Q042 Transcript, by Fielding M. McGehee III,” The Jonestown Institute, July 6, 2001, https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=29079.